Charles Dickens' gift to the world was Christmas Carol, but what does it still mean to us?

‘A Christmas Carol’ exposed poverty and gave us an image of Christmas that still endures. As an exhibition about the book opens, we look at what it still means to us

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For many of us, Christmas – in our imaginations at least – is a distinctly Dickensian affair. Candlelit tables are laden with succulent roast birds and flaming puddings, merry carollers wend their way along snowy streets, families gather harmoniously for fireside stories and games.

The reality may well be more shop-bought, drizzly and fractious, but our Christmas cards, advent calendars and television series (this year the BBC is offering Dickensian, a mash-up of the author’s characters) attest to our rather romantic seasonal attachment to all things Victorian.

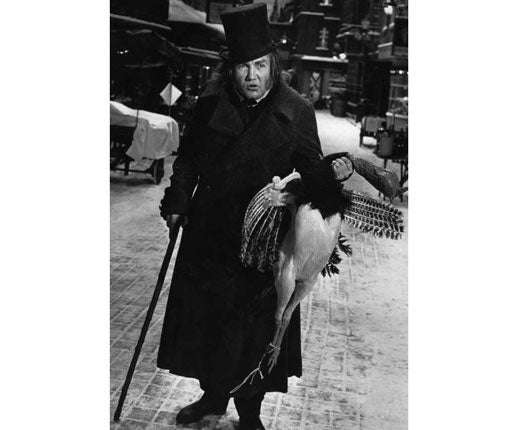

A Christmas Carol, published on 19 December 1843, was an instant success. The first run of 6,000 copies sold out by Christmas Eve. In print ever since, it has also spawned countless adaptations for stage, screen and song. The miserly Ebenezer Scrooge – joyously transformed by the visitations of the Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present and Yet to Come – has been portrayed by Alastair Sim, Albert Finney, Michael Caine, Marcel Marceau, Jim Carrey and, currently, Jim Broadbent in a West End production. Set to join the list in 2017 is rapper Ice Cube.

It has often been said that, in this much-loved story, Dickens invented Christmas as we know it today. Louisa Price, curator of the Charles Dickens Museum – based in the author’s first London family home and decorated for weeks now in a traditional Dickensian Christmas style – says that while A Christmas Carol was instantly influential, the truth is less straightforward.

“He clearly taps into a lot of traditions that we still hold dear: families getting together, wintry weather, special atmosphere, cosy gatherings. It is a story about compassion and good will at Christmas and we still gravitate towards this sort of tale. The book definitely put Dickens centre-stage at Christmas.”

That the festival was hitherto non-existent is, though, inaccurate. “Dickens made Christmas fashionable again, but it was celebrated well before his time,” says Price. “Always popular with the masses, it had fallen out of favour among the metropolitan middle-classes.”

During the 18th and early-19th centuries, industrialisation had transformed the nation. “People were moving from rural communities – perhaps centred round a stately home – and moving into the city,” explains Price. “Nuclear family became more important. People were working longer hours and they had less time off over the season. The way society gathered had changed.”

There was, Price says, an established market for seasonal publications, with two almanacs, Forget Me Not and The Keepsake, popular since the 1820s. Dickens took the genre to a new level. “He undercut them, making Carol cheaper but really investing in the presentation, with a cinnamon cloth binding and beautiful illustrations by John Leech.”

Literary circles were charmed. The author of Vanity Fair, William Makepeace Thackeray, declared that the novella “occasioned immense hospitality throughout England; was the means of lighting up hundreds of kind fires at Christmas time; caused a wonderful outpouring of Christmas good feeling...”

Celebrated letter-writer Jane Carlyle notes that after reading the book, her husband, the historian and essayist Thomas Carlyle, dispatched her to buy their first turkey.

Yet while A Christmas Carol is Dickens’ best-known festive story – and his most successful – it was not his first. In 1835 he had published A Christmas Dinner – a lively depiction of the big meal, complete with timeless concerns about family politics – and in the 24 years after 1843, he produced 22 further seasonal stories.

“That man must be a misanthrope indeed, in whose breast something like a jovial feeling is not roused – in whose mind some pleasant associations are not awakened – by the recurrence of Christmas,” he wrote in 1835.

Clearly, says Price, the man loved Christmas. “He came from a family with strong traditions of gathering together and doing a lot of the things that are described in the Carol.” Many of the scenes in A Christmas Carol reflected those in his life. Extended family and friends were welcomed, the house and table were decorated with evergreens, toasts were raised and parlour games and homespun shows – Dickens himself performed magic tricks for the children, Blind Man’s Buff was another favourite – were encouraged.

“One of Dickens’ daughters recalled him taking them down to a toyshop in Holborn and patiently waiting for them to choose their gift for Christmas,” says Price. Oldest son Charley remembered being brought down from the nursery to fill a place at one festive feast after the non-appearance of an expected guest.

As we see in the metamorphosis of Scrooge and the touching celebrations of the Cratchits – poor and worried for disabled Tiny Tim – Christmas was to Dickens also a time for gratitude, generosity and hope.

“Reflect upon your present blessings – of which every man has many – not on your past misfortunes, of which all men have some. Fill your glass again, with a merry face and contented heart. Our life on it, but your Christmas shall be merry, and your new year a happy one!” he wrote in A Christmas Dinner.

The moral behind A Christmas Carol is clear and intentional, though. Dickens’ outrage at the conditions faced by Britain’s poor is well-known. The story was his inspired way of highlighting the problem and exhorting the rich to action.

Earlier in 1843, the findings of a Parliamentary report into child labour had shocked Dickens. He also toured a Ragged School in London’s Clerkenwell and visited his sister Fanny (whose son is thought to have been the inspiration for Tiny Tim) in Manchester.

“He was incensed,” says Price, “and decided he would publish a political pamphlet called Benefit of the Poor Man’s Child. Within days, though, he tells friends he will defer his action until Christmas and that the result will be 20 times more powerful.”

He began writing in October, completing the story in six weeks. The book was intended to be read aloud, something he himself first did publicly that year and continued to do until 1870, the year of his death.

The traditions of the celebrations remained largely relevant then as they do now. In 1843, turkey – such as the giant one Scrooge has sent to the home of the Cratchits, having seen their meagre Christmas Day goose – was an emerging trend, imported from the New World.

Dickens received turkeys – as well as pork pies and ducks – from friends including his lawyer, publisher and his benefactor Angela Burdett-Coutts, the latter’s bird so large, he writes, that he initially mistook it for a baby.

This was also the year in which Christmas cards were first sent, the mass production of many printed goods being a result of industrialisation. Their wording is reflected in Scrooge’s happy declaration of “A merry Christmas to every-body! A happy New Year to all the world!”

It is this message – of compassion and goodwill – that Price believes underpins our continuing affection for Dickens at Christmas. Alongside the wintry imagery, the mouth-watering feasts and the cosy firesides, we are heartened by Scrooge’s eventual humility and generosity.

This year, the Charles Dickens Museum has asked illustration students from Central Saint Martins to create pieces inspired by A Christmas Carol. Many of them, says Price, have applied his words to 21st-century issues. “Responses to the refugee crisis, homelessness, ethical manufacturing all seem relevant. Perhaps, in the face of increasing commercialisation, we are looking for a more thoughtful message for Christmas.”

For details of Christmas events at the Charles Dickens museum see dickensmuseum.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments