Charles Dickens: A tale of two centuries

Susan Elkin selects the best of the new books being published to celebrate Dickens's bicentennial year

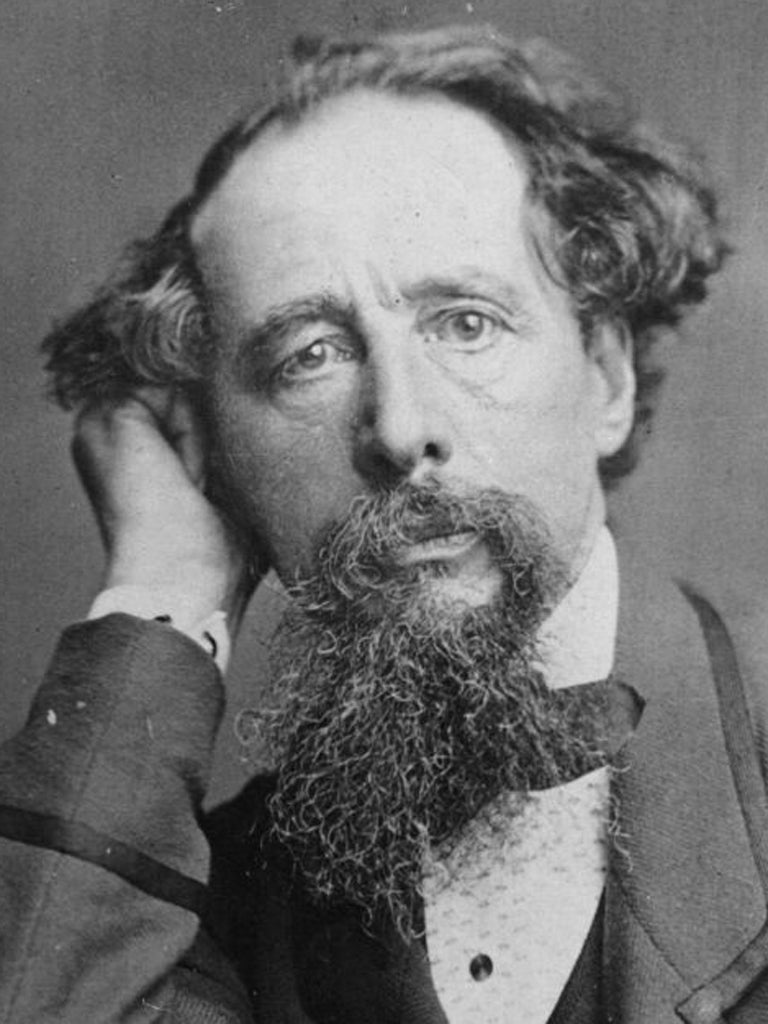

If Charles Dickens were as immortal as his writing, he would be celebrating his 200th birthday on 7 February. He may be – like Jacob Marley – as dead as a doornail, but culturally he's never been more alive, thanks to all of those timeless themes in his work. We are still wrestling with Orlick-style crime; punishment for men such as Sykes; daunting lawyers such as Jaggers; greedy industrialists such as Merdle and terrible poverty for Oliver Twist-like children. And family anxieties, tensions, miseries and joys – think Micawber, Pocket, Cratchit, Wemmick and Gradgrind – have changed remarkably little.

It is no wonder that, in addition to its recent adaptations of Great Expectations and The Mystery of Edwin Drood, the BBC very successfully moved an entire novel to modern India in its recent The Mumbai Chuzzlewits, adapted for Radio 4 by Ayeesha Menon. The material, which poured out of the kind, ruthless, workaholic, radical, campaigning Dickens, is ageless.

It is also why, in acknowledgement of his bicentenary, the Dickens commentators, critics, editors and creative responders have been busy producing new books. Hard on the heels of Claire Tomalin's excellent Charles Dickens: A Life (Viking, £30), published in October last year, comes Charles Dickens and the Great Theatre of the World by Simon Callow (HarperPress, £16.99).

As the 21st-century actor most closely associated with Dickens, Callow brings out Dickens's passion for theatre. He takes us from living-room theatricals in Dickens's Portsmouth childhood to those gruelling, ultimately fatal dramatised readings which Dickens undertook with rock star charisma and extraordinary energy in Britain and in America. (He disliked the latter far less on his second visit in 1867-68.)

Callow, who has a number of books and a lot of journalism to his name, writes with great authority and elegant insouciance, which makes this "biography with a twist" very entertaining. "At his writing desk, he felt like an emperor; in the theatre he felt like a god," Callow tells us. And he gives us a neat summary of Dickens's relationship with his exasperating father, who was the model for Mr Micawber. "Dickens was not unaware what a boon it had been for him as a writer to be brought up by a father given to such utterances, to say nothing of his industriousness and sunny temperament."

Don't be put off by the rather dull title of John Sutherland's The Dickens Dictionary (Icon Books, £9.99). Sutherland, as always, wears his erudition lightly, and his love of the quirky and off-beat shines warmly through this enjoyable book, which often made me laugh aloud. It isn't even really a dictionary. Rather, Sutherland takes 100 themes, ideas, Dickensian bits and pieces and biographical fragments arranged alphabetically from Mr Sleary's "Amuthement" to "Zoo Horrors" via serendipitous headings such as "Cauls", "Gruel", "Nomenclature" and "Onions".

Each section comprises a short, upbeat essay written in concise, witty, Hemingway-esque prose. Sutherland tells us under "Blue Plaques", for example, that "Dickens has left more blue china in his wake than most notables", or, under "Children", that, from his marriage in 1836: "Thereafter children came thick and fast – in his homes and into his narratives."

In a different mood, Dickens and the Workhouse (Oxford, £16.99) is Ruth Richardson's engaging account of her recent discovery that, the young Dickens lived only a few doors from the Cleveland Street Workhouse, which still stands in central London, and which presumably inspired Oliver Twist. She paints a colourful picture of the rich and the poor, the landlords and lodgers, the clerks, shopkeepers and outcasts of the area. And she's strong on the changing times, the politics, and social conditions through which she traces Dickens's interests and his emerging career as a writer.

Although Dickens burned almost all the letters he received in an angry fit of privacy defence in 1860, he wrote an enormous number and it would seem that, as Sutherland remarks, just about anyone who ever received a letter from Dickens kept it. These letters are an important source for all the books so far mentioned. So it's good to have editor Jenny Hartley's new selection of 450 of them. The Selected Letters of Charles Dickens (Oxford, £20) gives us missives ranging from the very formal and transactional to the reflective, excited, angry and personal – many to his friend and posthumous biographer John Foster – and some exquisitely graphic ones from America.

If you want more information about those letters, the plots of the novels, their publishing history or Victorian context, the people in Dickens's life and far more, try the new bicentenary edition of Paul Schicke's very full and useful 1999 "dipping" book, The Oxford Companion to Charles Dickens (Oxford, £25) which now has an engaging foreword by Simon Callow.

And finally, here's an imaginative spin-off. Tom-All-Alones by Lynn Shepherd (Corsair, £12.99) is a novel rooted in Bleak House, although you don't need to have read Bleak House to enjoy it. It's a highly compelling, immaculately written 19th-century murder mystery with a lot of Dickensian references in the language, featuring young detective Charles Maddox and the sinister secrets which Edward Tulkinghorn is determined to conceal at any cost. There's a slightly post-modern sense of looking back at a less enlightened age from a 20th-century perspective, and Shepherd can be franker about the evils of prostitution and the disposal of unwanted babies than Dickens could. It's an engaging read.

The Dickens Dictionary: An A-Z of England's Greatest Novelist, By John Sutherland, Icon £9.99

"Bastards: Children born out of wedlock are as common as fleas in Dickens's dramatis personae (16,000 characters make up the population of the Dickens world, it's reckoned). Fagin's little pickers and stealers are almost certainly illegitimate. At least half the sad enrolment of Dotheboys Hall in 'Nicholas Nickleby', one can plausibly assume, are legally unowned by any parent"

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks