Boyd Tonkin: The emigrant who haunts our literature

The Week In Books

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Some ghosts develop more solidity, and even audibility, as the years pass. WG Sebald, the writer who above all others transformed the ravaged lands and minds of post-war Europe into a scene of hauntings, has grown from a wraith into a titan since the car crash in Norfolk that took his life late in 2001. Like many people who knew Max a little, and admired his work a lot, I have watched with both delight and alarm as this gentlest of geniuses has swollen into a cult of rock-star dimensions.

Perhaps all the posthumous acclaim took off when Austerlitz – in Anthea Bell's majestic translation – won the Independent Foreign Fiction prize a few months after the author's death. Throughout the last decade, the belated tributes snowballed. Last month, the Grand Palais in Paris hosted a conference about Sebald's work – by no means the first. Writers from as far apart as Denmark and Colombia have shared their reverence for Sebald with me as if confessing some forbidden faith. Yes, Max was an exquisitely sensitive soul who magicked the pain of a dire century into prose art of astonishing subtlety. But he was also a deadpan wit who would have chuckled at his own hushed beatification. In a new memorial poem, "Traffic", his former colleague Andrew Motion nods to this side of Sebald, which readers should always prick up their ears to catch: the "humour in your voice".

Next Monday, Will Self will mark the 20th birthday of the unique public institution that Sebald founded. The author of The Emigrants, The Rings of Saturn and Austerlitz had left Germany for England in 1966 to teach, just as the Auschwitz trials both opened the eyes of this late-war baby (born in Bavaria in 1944) and convinced him that the work of remembering and restitution in his native land had barely begun.

During his more than three decades on the staff of the University of East Anglia, he created the British Centre for Literary Translation: in itself, a legacy to cheer and cherish. In this year's Sebald Lecture (at Kings Place in London), Self will discuss the Holocaust in the work of Max and other non-Jewish authors: the absent centre that moulded nearly everything he wrote.

As a model of tact and a talisman against kitsch, Sebald's shot-silk tapestries of document and dream remain indispensable. And I will never forget that tact in action, on the day that I first met him at UEA for an interview when his ghost-crowded, visionary record of a walk down the Suffolk coast, The Rings of Saturn, appeared in English. I remember the ominous postcard of Brueghel's "Fall of Icarus" on his office door; his sardonic gaze around the modernist utopia of the Sainsbury arts centre; his disdain for the concrete ziggurats that roasted students in summer and froze them in winter; his fascination with the old photos trawled from markets and junk-shops that acted as a spectral commentary in his books, and his wry compassion for these long-lost figures, marooned in the past: "We're dead. Can you do something about it, please?" Max could, and did.

And I remember the grammatical finesse of his reply to a clodhopping question about whether German chancellor Willy Brandt's kneeling homage at the monument to the Warsaw Ghetto uprising should have won the approval of Holocaust survivors. "If I had been numbered among the victims, I should have been inclined to accept the gesture". No writer has ever dwelt with such courage and insight on the stony, painful path of memory for those not "numbered among the victims". Those victims, as The Rings of Saturn and On The Natural History of Destruction show, meant the deleted casualties of ideology and technology wherever they suffered, from colonial outposts to razed German cities. To remember him is to remember them. Treat his books not as a shrine but as a compass.

Will Self will give the Sebald Lecture on Monday 11 January: www.kingsplace.co.uk

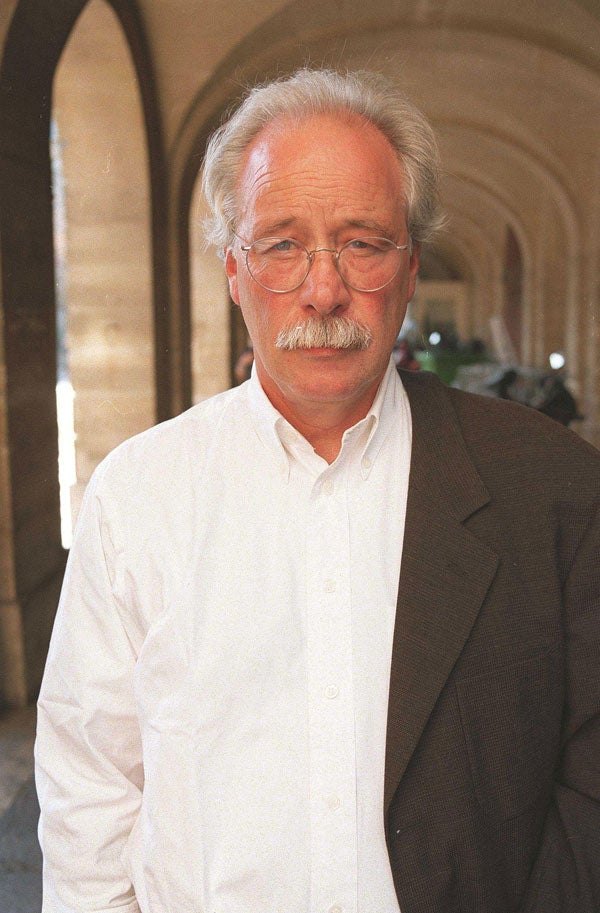

P.S.Literature and royal medals make uneasy companions. Many renowned authors quietly decline gongs. But sometimes, as with this new year's honours list, the palace nod allows under-sung heroes to move into the spotlight for a while. Anthea Bell – selected last month as one of this paper's literary heroes of the decade - now has an OBE for her vast and varied contribution to the art of translation. Three more-than-merited MBEs mark the achievements of Harry Chambers, stalwart publisher of Peterloo Poets, the performance poet – and tireless enthuser of new audiences - Lemn Sissay (left), and Honor Wilson-Fletcher, ex-director of the National Year of Reading and one of those precious backstage dynamos who do so much to keep good books, and readers, thriving in harsh times. Republicans and royalists alike should salute them.

b.tonkin@independent.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments