Boyd Tonkin: Oddity that stands the test of time

The week in books

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Generally on target when it came to literary reputations, even Dr Johnson sometimes goofed. "Nothing odd will do long," he famously misjudged. "Tristram Shandy did not last." Not only did Sterne's wildly eccentric comic epic endure to cast its spell over modern novelists around the globe (not least in Latin America, which would truly have flabbergasted Sam). The first part of his proposition also tanked. You might even argue just the contrary: that in literature the "odd", the weird, the fantastic, the childish and the extravagant (all those genres that the anti-romantic Johnson so distrusted) have shown a more robust ability to cross borders of taste, territory and time than mature realism in feeling and style. Jane Austen revered Johnson and wrote in his vein. Yet, for all her local renown, if you were to ask which novel by an Englishwoman written in the 1810s continues to inform and inspire world literature, there could be only one credible answer. It would be Mary Shelley's Frankenstein.

Turn to the icons of High Victorian fiction, and a similar picture takes shape. Champions of George Eliot will find a faintly distressing aside in This is Not the End of the Book, an entertainingly free-range dialogue about writing past, present and future between Umberto Eco and the screenwriter and author Jean-Claude Carrière (translated by Polly McLean; Harvill Secker). Eco mentions that one of the trio of publishers in his novel Foucault's Pendulum is called Casaubon, and that some critics had assumed an allusion to the dry-as-dust scholar in Middlemarch. Eco reveals that he had long ago read Eliot's masterwork – but that it bored him and left so faint a trace that he had forgotten her use of the name. On the other hand, literary luminaries in the Eco mould never fail to cite among their touchstones and talismans a pair of books which (like Middlemarch) also reached completion in 1871: Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass.

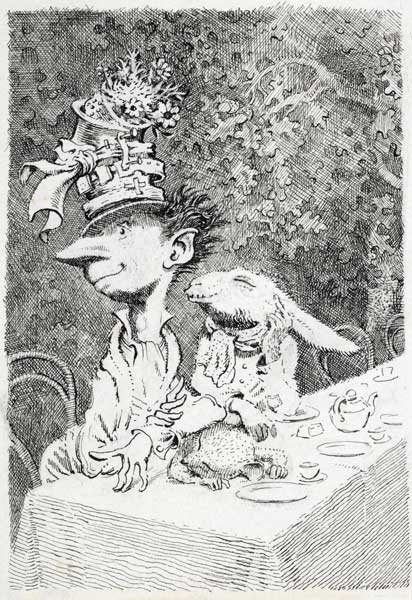

The work of Alice's creator Lewis Carroll has attracted some wonderful artists, none more memorably quirky than Mervyn Peake. His illustrations will adorn a new exhibition at the British Library - from 5 July - to mark the centenary of the writer-artist's birth in China. Peake's anniversary will make something of a splash, with a memoir by his daughter Clare, a lavish illustrated edition of his Gormenghast trilogy from Vintage Classics, a Radio 4 dramatisation of the books, and a "fourth volume" in the series: Titus Awakes, completed by his widow Maeve Gilmore after Peake's death in 1968.

In Johnsonian terms, nothing "odder" than Peake's densely imagined Gothic-grotesque world of Gormenghast came out of postwar England (the trilogy's publication spans 1946 to 1959). And it has lasted. Underground classics in the Sixties and Seventies, the Gormenghast books now snare the admiration of a new generation. Even Sebastian Faulks, no one's idea of a flaky Gothic fantasist, smartly chose Peake's homicidal arriviste Steerpike as an exemplary "Villain" in his recent TV series.

Indeed, look at postwar English writing as a whole, and the oddballs have fared much better than the sobersides. Does fantasy regenerate – by virtue of access to the eternal flames of myth and archetype - while timebound realism expires?

George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four came out in 1949, and still chills millions for whom Cold War politics mean next to nothing. The first half of the 1950s saw the publication of JRR Tolkien's Lord of the Rings and CS Lewis's Chronicles of Narnia sagas. From The Day of the Triffids in 1951 onwards, the same period produced John Wyndham's eerie landmarks of SF. Take as your yardstick a long-haul appeal to readers across many decades and cultures, and you might claim that the "mainstream" English fiction of this age unrolls across a galaxy of madcap imaginary planets.

Yet the forms of fantasy, then or now, need not imply escapism or indifference to the history of the times. Peake himself visited the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp as a war artist after its liberation in 1945. The relationship between the all-too-real horrors of totalitarian power and the Gothic scenarios of Gormenghast remains an ever-provoking puzzle for his fans. In the fantastic fiction that renews its audience, romance and reality will mysteriously intersect. And when they do, the odd will last.

A book club with a touch of class

In the recent past, the news that Waterstone's had teamed up with a fashion and lifestyle magazine for a book club offering readers 50 per cent off the price of its picks would have raised few hopes about the quality on show. But sneery snobs, fall silent. The roll-call of books selected for the tie-up between the chain and Grazia looks fairly impressive. Authors include Orange Prize winner Téa Obreht, Sofi Oksanen, Siri Hustvedt, Paul Murray, Jennifer Egan, Lionel Shriver, Christos Tsiolkas and Maggie O'Farrell (above). I hope the venture thrives. It might prompt Richard & Judy, whose book club choices for WH Smith have become formulaic and predictable, to raise their game.

The big tax break in small print

Which cultural activity enjoys a £600 million annual subsidy from the UK government that no one notices? Well, not many people do. The zero-rating of books for VAT represents a vast hidden boon for a £3.1 billion industry. It also greatly irks the European Commission. Yet the exemption only applies to printed works. E-books incur the full 20 per cent. Across Europe, publishers have urged the EU to narrow the gap between the taxes on print and electronic reading. Antoine Gallimard, from the great French house of that name, explains in a petition that "EU taxation law is to blame, which holds that the book, as soon as it is downloadable or accessed online, is deemed to be considered as a service, not as a sale of a cultural good." This week, Penguin UK chief John Makinson said that he has raised the anomaly with the Chancellor, but doesn't want to press in case the Treasury seeks harmonisation – upwards, with VAT on print. He shouldn't panic. Zero-rating also benefits those snarling papers the PM so fears.

b.tonkin@independent.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments