Books of the month: from Jonathan Coe’s new novel to a joint biography of Joan Didion and Eve Babitz

Martin Chilton shares his November reading highlights

Alan Bennett turned 90 in May and the marvellous old trouper shows flashes of his famously droll wit in Killing Time (Faber), a novella set during the pandemic in a home for the elderly called Hill Topp House. Incontinence, coffins and crematoriums – and an old man who has trouble locating his penis – all come into a story that is easy to digest but has the somewhat sad texture of an eccles cake that has been left too long in the glass display cabinet.

Meanwhile, sprightly 75-year-old Haruki Murakami will surely delight his devotees with The City and Its Uncertain Walls (Harvill Secker, translated by Philip Gabriel), which is a story of love and a quest, as well as a celebration of reading and the libraries that house the world’s wonderful books. The Japanese master’s new novel is also a parable for the bizarre post-pandemic times, now becoming such a feature of some of this decade’s fiction.

If you are after something completely different, then here’s a recommendation for Joan Smith’s Unfortunately, She Was a Nymphomaniac: A New History of Rome’s Imperial Women (William Collins), in which the author of Misogynies looks at the long shadow of Roman misogyny. Smith writes with great force about how women were abused and murdered on a horrifying scale in ancient Rome – and highlights the influences the empire has had on the modern-day world. Misogyny certainly wasn’t built in a day. As Smith shows, Rome played its part in fostering present cultures, in which male violence is all too common.

The letters of Oliver Sacks, children’s fiction by Maggie O’Farrell, a novel by Jonathan Coe and non-fiction by Tim Robey, Lili Anolik and Guy Leschziner are reviewed in full below.

Box Office Poison: Hollywood’s Story in a Century of Flops by Tim Robey ★★★★★

Some books are off to a promising start simply because they are built on the foundation of being a cracking idea for a publication. A case in point is a history of Hollywood through a century of films that stand as the medium’s “weirdos, outcasts, misfits and freaks”. Put that idea together with the insight, humour and sharp judgement of one of Britain’s best film critics (I worked with Tim Robey at the Telegraph and cheerfully proclaim my respect for his work) and you have a winner.

The 26 chapters, covering films from 1916’s Intolerance to 2019’s Cats, are brimming with bizarreness and full of juicy details. Robey wisely leaves aside some stinkers that have been fully excavated before – such as Heaven’s Gate and Bonfire of the Vanities – and instead provides rich, sometimes shocking, details on trouble-strewn films such as Queen Kelly (1929), The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) and Howard Hawks’s 1955 epic Land of the Pharaohs, which was plagued by disasters including a fight among the minor cast that resulted in the death of one “extra”.

Robey’s extensive research unearths numerous illuminating and revealing quotes about his chosen movies (David Lynch admits with candour that filming Dune was “maybe 75 per cent nightmare”), and the anecdotes are often amusing and wince-inducing in equal measure. The tale of Terry Gilliam and his windscreen will brighten your day, but you may be left nauseated by reading about what Uma Thurman had to endure as a teenager at the groping hands of Oliver Reed. The book also puts flops into context – it was interesting to note Robey’s assessment that The Hudsucker Proxy’s “towering failure” ended up actually schooling the Coen brothers “in how not to do it”.

Ultimately, I am sure the book will leave you wanting to watch for yourself some of the cinematic messes in question (Robey calls them “stinky binbags”), including 2002’s The Adventures of Pluto Nash, a film that helped its star Eddie Murphy pocket $20m, nearly three times the amount the film grossed worldwide.

I read the book in one sitting (although it’s possibly best savoured slowly enjoying each entry as a separate entity), on a long train journey, during which I startled a woman next to me when I snorted with laughter at Robey’s account of the crummy 2019 Cats. Andrew Lloyd Webber’s third wife, Madeleine, said “I’ve never seen him so upset” after the creator of the original theatre musical watched Tom Hooper’s adaptation. She said Webber was so traumatised by the experience that he went out and bought “an emotional support dog” called Mojito.

The ludicrous comedy of that image is just one of the many reasons that Box Office Poison packs such a punch.

Box Office Poison: Hollywood’s Story in a Century of Flops by Tim Robey is published by Faber on 7 November, £16.99

Oliver Sacks: Letters (edited by Kate Edgar) ★★★★☆

Oliver Sacks, who died in 2015, was a world-renowned neurologist, best known for his books Awakenings and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat. His longtime editor, Kate Edgar, has done a fine job of compiling his correspondence, letters that reveal a sensitive, probing and humorous man.

The selected missives, running from 1960 to the year of Sacks’s death, reveal his struggle for acceptance, as both a scientist and a queer man born in London in 1933. They include dozens to his parents, Elsie and Samuel Sacks. In 1962, he tells them of the squalor and poverty of life in Mexico, the people so “pitifully thin and emaciated”, adding: “In the streets of Culiacan I saw a corpse lying in the gutter, probably dead of starvation, with nobody paying attention to it. When it starts smelling too high, they will collect it and throw it on the rubbish dump.”

The collection includes letters to writers such as WH Auden, Harold Pinter and Susan Sontag, and to strangers he enjoyed meeting on his travels. There is also a sweet letter to Robin Williams – who starred in the 1990 adaptation of Awakenings – and another to filmmaker Peter Weir, in which he reflects on the differences between the “explosive” character of Williams and that of his co-star Robert De Niro, concluding that De Niro strikes him as “a polar opposite – shy to an almost pathological degree”.

Sacks had a brilliant mind – and these letters reveal it further to the world.

Oliver Sacks: Letters (edited by Kate Edgar) is published by Picador on 7 November, £25

The Proof of My Innocence by Jonathan Coe ★★★★☆

Satire and murder mystery overlap in Jonathan Coe’s snappy new novel The Proof of My Innocence, set over a shifting period and pivoting around the murder of a political blogger in the summer of 2022.

The novel is full of humour – the jokes include ones about Liz Truss, a bishop’s privates and greedy antiquarian booksellers – as Coe, one of our finest modern novelists, gently skewers literary fads and the whole writing game. One character quips that what all authors are angry about is “lack of recognition”.

In his state-of-the-nation novel, Coe sharply depicts a Conservative-run Britain where fantasy took over from real life. The story also brings to life the comedy of the sinister political think tanks (whose origin story allows Coe to send up weird parts of academia) who have schemed over the past four decades to dismantle the NHS.

The dialogue is entertaining throughout – there is a splendid character called Phyl, a zero-hours sushi seller at Heathrow’s Terminal 5, who helps solve the murder – while also shedding light on the degraded society left for our youngsters to navigate.

The Proof of My Innocence by Jonathan Coe is published by Viking on 7 November, £20

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik ★★★★☆

Lili Anolik explores the complicated relationship between Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, who first met in June 1967, in this riveting account of two complex, elusive and humorous writers.

Didion & Babitz is a stimulating, provoking read (even the chapter titles, such as “Female Male Chauvinist Pigs”, hold your attention) by an author who conducted more than a hundred interviews with Babitz before the writer’s death in 2021.

I ended up with a stronger sense of Babitz than Didion – and a feeling of warmth for a unique, enigmatic character. Babitz was capable of being wounded and simultaneously ambivalent to fame and able to brush off criticism. When she received a stinging review for her novel Eve’s Hollywood from friend and critic Larry Dietz, Anolik notes, she was not caught by surprise: “The main thing about Larry was that he was a t***,” Babitz told the author.

Sexual sparks and sparky characters galore come into Didion & Babitz – including Joseph Heller, Jim Morrison and Jane Fonda – in a book which also serves as a portrait of a lost, bohemian time in America. The only sadness is reading about the decline of the main subjects. More uplifting are the examples of the blazing prose in the letters in which the pair argue about Virginia Woolf.

“I can’t stand meetings. I’d much rather figure things out from gossip,” said Babitz. If that comment raises an approving nod, I’m sure you’ll enjoy this fascinating slice of history.

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik is published by Atlantic Books on 14 November, £20

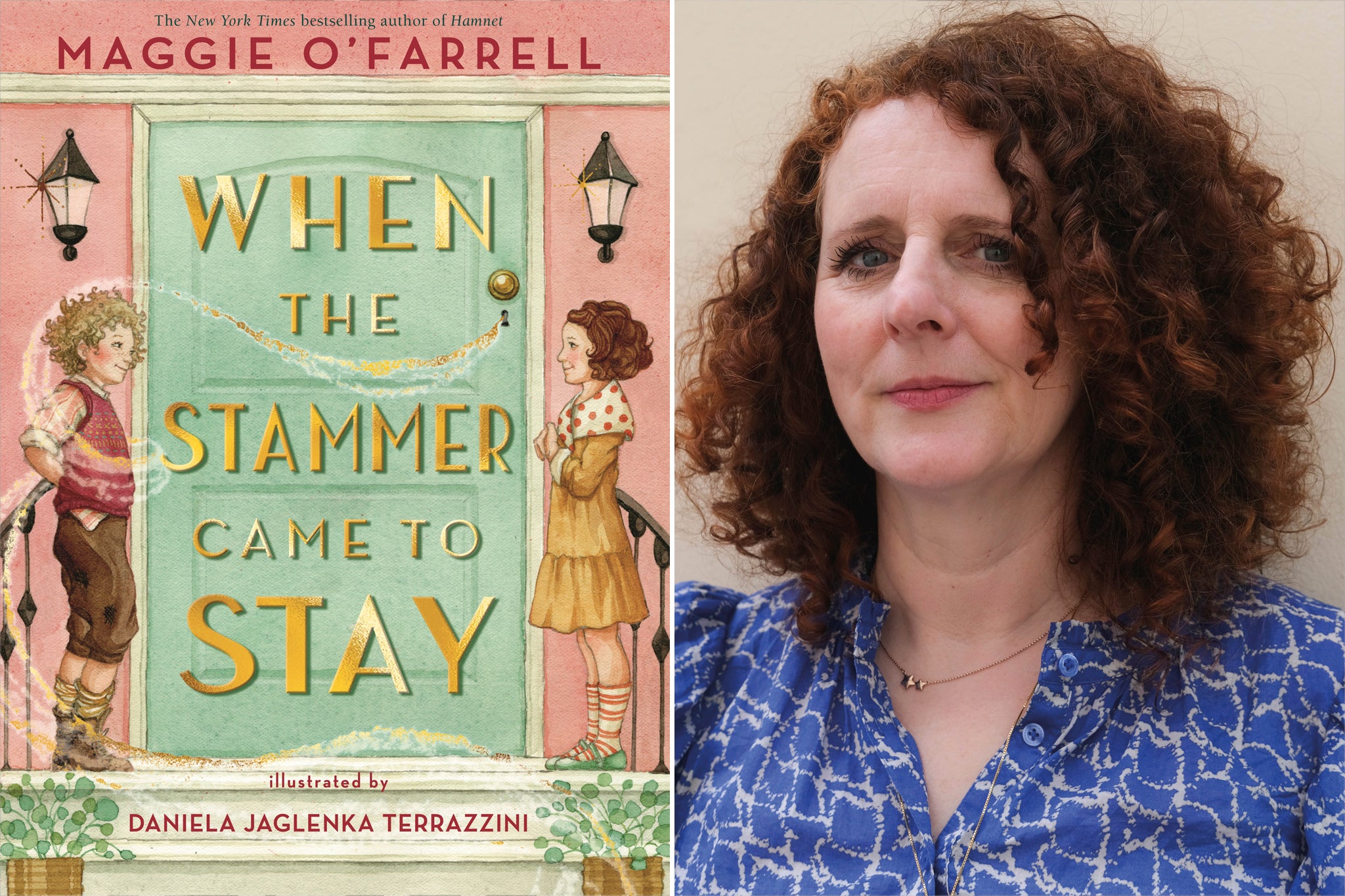

When the Stammer Came to Stay by Maggie O’Farrell ★★★★☆

Maggie O’Farrell, the author of the wonderful Hamnet, returns to children’s fiction with When the Stammer Came to Stay, a story about two contrasting sisters, Bea and Min. One day, as Min is chatting, her tongue feels locked and she begins to stutter. Min feels “scorched with embarrassment”, words all the more potent if you know that the book is based on the Derry-born author’s own personal experience with a stammer.

This heartwarming book – with gorgeous illustrations by Daniela Jaglenka Terrazzini that bring to mind the classic drawings by Shirley Hughes – ends on a positive message for young children: about looking for the good that happens in your life without you noticing.

When the Stammer Came to Stay by Maggie O’Farrell is published by Walker Books on 21 November, £14.99

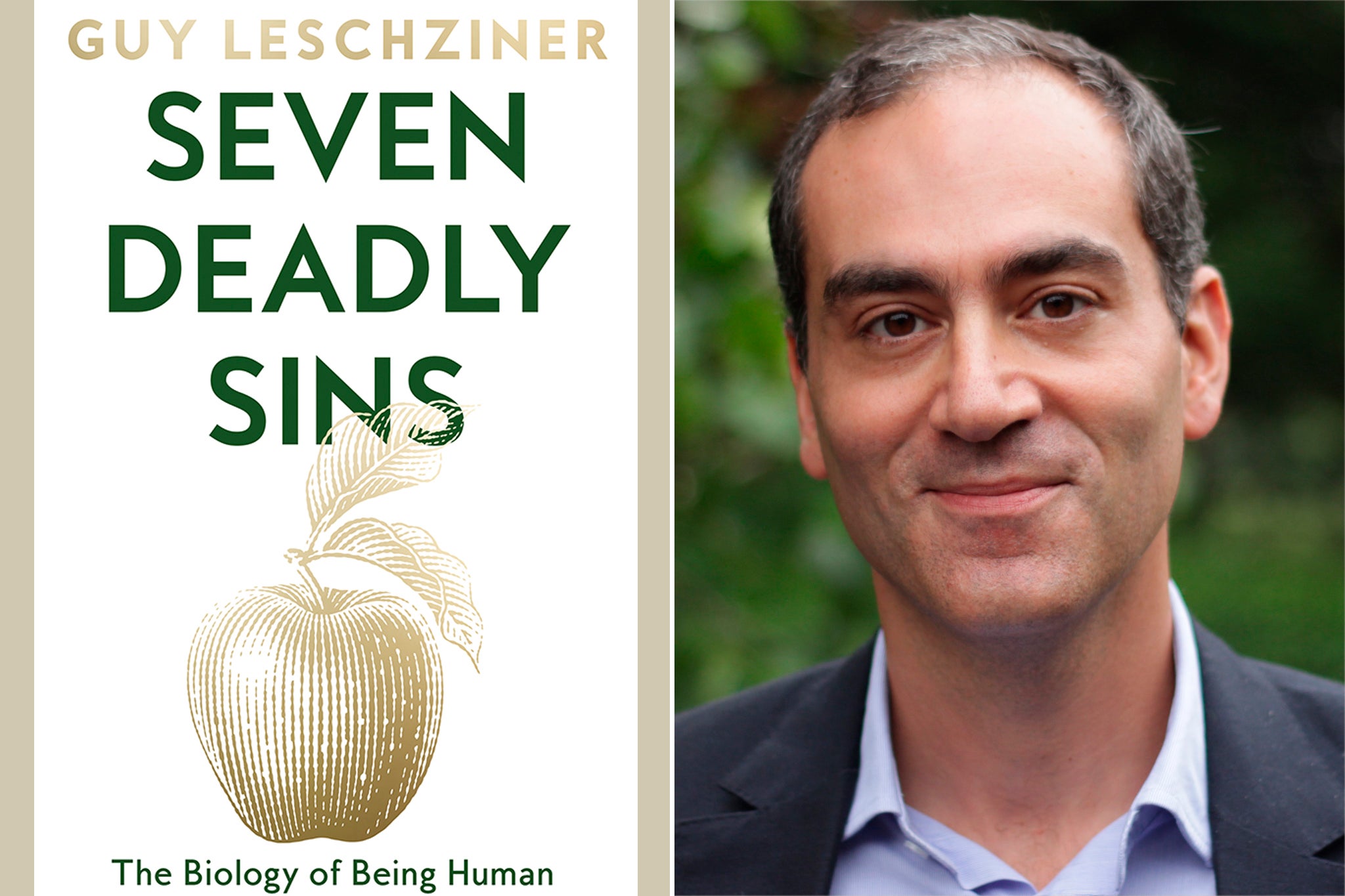

Seven Deadly Sins: The Biology of Being Human by Guy Leschziner ★★★☆☆

In the 1987 film Wall Street, Gordon Gecko famously contends that “greed is good”. Dr Guy Leschziner, professor of neurology and sleep medicine at Guy’s and St Thomas’ hospitals, has a rather different take on it in his Seven Deadly Sins: The Biology of Being Human. For a start, greedy people have less stable, satisfying relationships, he states.

Leschziner details the reasons in his erudite and case-packed study of “wrath, gluttony, greed, sloth, pride, envy, lust and anger”, the supposed “Seven Deadly Sins” that define human vices. In the book, he reframes sin from a biological perspective, encompassing genetics, neuroscience and evolutionary psychology as well as the nature of free will.

There are surprises, too, including about the benefits of losing your temper. “Anger has some very clear positive aspects,” writes Leschziner. “If individuals are given a puzzle to solve (one that is actually unsolvable), some respond with despair or dejection, while others respond with anger. When given a second puzzle, this time one that does actually have a solution, those who experienced anger with the first perform much better, and persist in their efforts for longer.”

Seven Deadly Sins: The Biology of Being Human by Guy Leschziner is published by William Collins on 21 November, £22

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks