Bloomsbury laid bare: The last member of the famous artistic set reveals all

They were the controversial literary and artistic set whose members were said to have 'lived in squares and loved in triangles'. In a rare interview, Olivier Bell talks about the discovery that throws new light on life at Charleston.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is more than 70 years since Virginia Woolf last put pen to paper. And 50 since her sister Vanessa Bell put away her paints. In 1941, Virginia filled her pockets with stones and walked out into the River Ouse, never to return. Vanessa died peacefully 20 years later, aged 81, after a bout of bronchitis. But the Bloomsbury Group – of which the sisters were among the leading lights – remains with us, its focus on personal relationships, ideas and aesthetics as appealing today as ever.

Charleston, the house in Sussex which became the country quarters of many of its members, is now a world-famous and much-visited museum. The numerous romantic affairs (some homosexual, some bisexual, most enthusiastic) between the men and women who made up this fluid set of friends, and their bold experiments in living arrangements (they were, it was said, "a group of people who lived in squares and loved in triangles"), continue to prompt biographies, films and plays, and have ensured a certain gossipy fame for the set.

But it isn't all tittle-tattle: much of the intellectual clique's artistic, political, philosophical and literary output remains widely respected today, while this summer the British Library is publishing – to no little excitement – possibly the last pieces of Woolf's unpublished work.

It was 1916 when Charleston first became a focal point for the Group. Vanessa Bell and her fellow painter – and lover – Duncan Grant rented this brick farmhouse, at the foot of a high point of the South Downs at Firle in East Sussex. They spent two full years there, living with Grant's other lover, the writer David "Bunny" Garnett; the two men worked on the land as an alternative to military service during the First World War, to which they morally objected (many of the Group were passionately, and radically, committed to pacifism).

From 1918, it became simply a holiday home, "for Sussex summers away from London", until 1939, when Vanessa and Grant moved back full-time. Charleston was where Vanessa's children – Julian and Quentin, whom she had with her husband, the art critic Clive Bell, and subsequently Angelica, her daughter with Grant – spent their childhoods.

In 1923, when Quentin was 13, he began to produce a regular "Charleston Bulletin", with tales and drawings teasing everyone who visited or lived there. He had plenty of subject matter. Visitors included John Maynard Keynes, Lytton Strachey and Roger Fry (see box, above). Quentin enjoyed himself a great deal. So did his aunt Virginia, who was happy to contribute, mostly for his special Christmas supplements. These are the final pieces of Woolf's work that will go on display for the first time in June.

"Julian and Quentin did the 'Bulletin' together at first, every day," remembers Quentin's wife, Anne Olivier Bell, known as Olivier, "but Julian lost interest quite quickly. Quentin enjoyed it and kept them going – nearly 100 altogether! Bad spelling, the lot. There were jokes, pictures, stories. Back then, nobody took the 'Bulletins' too seriously. They disappeared into a box and were forgotten," says Olivier, who is now 96.

Olivier is one of the few still alive who knew the group first hand. Her memory remains full of clear images of the toings and froings of the busy collection of artists, writers, philosophers and anyone else they thought interesting enough to have to stay.

Olivier has outstayed nearly all of them. Today, the small windows of her old Sussex cottage look out on to the fields and green slopes of the Downs, views with which she has been familiar for the past 60 years.

Pieces of Quentin's chunkily charming pottery (about which she smiles indulgently – "They keep breaking!") are on shelves and mantelpieces, and there is a black-and-white photograph of the art historian's benign, bearded face on the dresser. On his death in 1996, he also left behind a collection of writing and illustrations, both private and public.

A recent exhibition at Charleston showed examples of the latter, and his biography of his aunt Virginia, published in 1972, was a critical and popular success. "Leonard Woolf was always being bothered by people asking to write about [his wife] Virginia, so he finally asked Quentin to do it," recalls Olivier.

The book won numerous awards and (together with Michael Holroyd's biography of Strachey) contributed significantly towards bringing the Bloomsbury Group back into the public consciousness. It silenced naysayers, too, including the literary editor of The Times, who had declared that nobody would read it.

Quentin was lucky to have the diligent Olivier to check and unearth facts, anecdotes and other information: "From Virginia's diary, Leonard had published only the bits about her writing, and had cut out bits that mentioned people: an awful lot was in pieces in envelopes! I put them all together," she says now.

The success of the biography prompted another project – Olivier's editing of Woolf's diaries. This was a mammoth task, involving serious scholarship and considerable diplomacy (Woolf was always candid, occasionally downright bitchy, in her descriptions of others). Olivier worked on the diaries for 20 years, and published each of the five volumes as it was finished, to considerable acclaim. She became a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and received two honorary doctorates.

Meanwhile, academic and public interest in Woolf had mushroomed in the latter half of the 20th century; her work was particularly embraced by second-wave feminist academics, and her novels achieved canonical status. The love lives and inter-connected relationships within the group were also a treat for writers, historians and journalists, while many of the group's writings were republished, artworks re-assessed. Bloomsbury was well and truly back.

Olivier's life did not start with Bloomsbury, however. Her mother, Brynhild Olivier, was a well-known beauty who had caught the eye of the First World War poet Rupert Brooke, while her father AE (Hugh) Popham was Keeper of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum and an expert on Leonardo da Vinci.

Olivier herself studied Art History at the Courtauld, where she met Graham Bell (no relation to Clive), a penniless South African painter. They were to meet again, in Paris in 1937. They started a relationship, and decided he would divorce his wife Anne in order to marry Olivier. This turned out not to be possible and to her great grief he was killed in the war. Before his death he had painted her portrait.

Living in London during the war, Olivier was very active: in 1939, she was an air-raid warden. "Then in 1941 I was at the picture desk of the Ministry of Information, and volunteered as a motorcycle despatch rider as well."

In 1945, Olivier was posted to Germany, and stationed at the Divisional Headquarters of the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives Programme (MFAA), co-ordinating the branch officers' work. This consisted of tracking down works of art appropriated by the Nazis, with a view to restoring them to their rightful owners. She is the only surviving British member of what became known as the "Monuments Men" (a film about them, called simply The Monuments Men and starring George Clooney, is due out later this year). For this work she was honoured by the United States government in 2007 – though not by the British government, which has never recognised the achievements of the MFAA.

Olivier encountered the Bloomsbury Group for the first time in Paris in 1937. She was visiting her friend Helen Anrep (the long-term partner of Roger Fry), who was staying at the same hotel as Vanessa Bell. "As we were leaving for dinner," Olivier recalls, "Helen pointed over the lobby balustrade to a group gathered below: Vanessa, Quentin, Duncan Grant and his and Vanessa's daughter, Angelica. I had never met Vanessa, but she looked devastated. I learnt that she had only just heard about the death of her son Julian in the Spanish Civil War. We didn't say anything to them at all as we passed – it would have been completely inappropriate."

At the end of the war, Olivier met Vanessa again, in happier circumstances. "She was lovely and asked me to sit for her at Charleston," she explains. "At that time, in Austerity Britain, artists had a hard time finding canvases and paints, so the Arts Council commissioned various artists to undertake large-scale paintings, and provided them with the materials to do so. Vanessa was one of them."

Grant met Olivier, for her first visit, at Lewes station in the horse and cart kept for such occasions. This was not used very often. "Except for Vanessa, they were great walkers," remembers Olivier. "Just as well. No car, buses not good: you walked down the road to catch one, or you got a taxi from [the nearby village of] Berwick.

"When we got to Charleston, Clive [Bell] was there – he was pretty scary. And Quentin and Vanessa. We had dinner around the table and coffee in the sitting-room. The next day I sat in the drawing-room and Quentin looked in through the open French window and modelled me. It was hot, I remember. Quentin was big and fat and had a large ginger beard."

Later, Olivier and Quentin talked of summer plans. "I had two weeks' holiday and I wanted to go to Greece. It cost too much to fly there, and it took three days by rail. We talked about it and decided to go to Italy instead. Quentin gave me a kiss on the way to the station, I think… or perhaps I kissed him. It was a long time ago!"

It was the start of a romance, and they married in 1952. "Quentin had a small private income which was not enough to keep a family, so, with me, and a baby on the way, he needed a job." He found one in the art department at Newcastle University, for five years, before becoming Professor of Fine Art at Leeds University. "[He] moved us all to a lovely house on the edge of the city, where we lived for the next seven years." k

But the Bloomsbury Group epicentre of Charleston was still very important to them: "We would spend a month or two every summer at Charleston," Olivier remembers.

Olivier's daughter, Virginia Nicholson (who was named in honour of her famous great-aunt, and has also written books about Charleston and the Bloomsbury bohemians) wrote of her vivid memories of the farmhouse in a piece for American Vogue, in which she described the interior which Vanessa and Grant had painted and decorated vividly: "The rooms were a progress of colour and pattern: the green dining-room table was adorned with a necklace of white circles against a salmon background; it glowed in front of black walls, hand-decorated with chevrons in grey, against which hung vivid paintings… Flowers and sculptural forms in pink, lemon and green processed across doors and cupboards, whilst, against an azure sky, full-bosomed goddesses presided over the fireplace."

Despite this riot of creativity and colour, it was by no means luxury living. True, there was Grace, the housekeeper, "who came from Norfolk aged 18, and stayed till she was 70", but it was pretty rural. Comfortable, but basic. "I slept in the spare room, and could hear the calves mooing while I fed my babies," Olivier recalls.

And Olivier and Quentin were destined to move back to their much-loved Sussex countryside permanently. The historian Asa Briggs "invited Quentin to join him at the nearby Sussex University, and so we moved, in 1969, to a house three miles from Charleston", says Olivier. "Vanessa and Clive were both dead by then, but we saw Duncan [Grant] often."

Olivier's daughter has written about this time with affection, and some sadness: "In his nineties, Duncan was as merry and spirited as ever, never without a cigar and a busily sketching pencil. When he died in 1978, Charleston very nearly died too."

Charleston and its influence, which had been controversial in the early part of the 20th century, had faded by the time of Grant's death. Vanessa and Grant's art was firmly out of fashion and their house was suffering from neglect. The wallpaper was flaking, the paint was chipped, the roof was leaking, and the full-bosomed goddesses were presiding over a fireplace that had become sadly dilapidated.

Olivier recalls ruefully that, "It was all a terrible mess – a wreck. Nobody bothered. Luckily Quentin and others realised that it was a unique and extraordinary place, and thought it should be preserved." A fundraising committee was set up, but it took six years to raise the money required. Over the next five, it was spent on restoring walls, roof, wallpaper, woodwork…

Now Charleston is renowned worldwide and open – during its season – to all. Yet it still feels off the beaten track. A narrow, bumpy lane runs between fields up to the farmyard, and turns towards the square stucco house, covered with Virginia creeper, clematis and roses.

The 25,000 visitors who come each year find an unpretentious home whose now-dead tenants still whisper their presence in the rooms and corridors. Every surface – walls, lampshades, screens, chairs and tables – is decorated, the studios waiting for sitters to take their places on chairs by windows that look out on to a carefully planted but exuberant cottage garden.

Charleston's tenants produced their work among the feathers of cow parsley, the smell of manure, the buzz of bees, the shadow of white chalk slopes – and this has not changed. The house is tidier, the visitors respectful, but it keeps its sense of quiet, creative possibility.

Olivier – who better? – is senior trustee, and will remain so for her lifetime. She looks over articles for the Friends of Charleston magazine Canvas, and rare is the error that slips past her beady eyes. Money is always needed, as is the way of these things, and Quentin, from beyond the grave, continues to contribute.

After Quentin died, Olivier discovered an old box in the attic. In it were nearly 100 "Charleston Bulletins", their old pages evoking everyday life at Charleston in a way that paintings and more serious pieces of work cannot. The jokes are still funny, the drawings jolly, the teasing sharp and clever. Virginia Woolf's six or so contributions to the Christmas issues were there, handwritten by her or dictated to her nephew.

She mocks Clive Bell, who "attained his present undisputed eminence in the world of Art and Letters by his skill in the science of equitation"; Quentin provides the illustrations, of Clive riding a horse, and striding along clutching a book marked "KEATS" under his arm. Trisy, a cook, also comes in for gentle ribbing – she makes "dozens and dozens of pancakes", although her porridge is described by Woolf as "a very different affair. This was close… and crusty. It dolloped out of a black pan in lumps of mortar. It stank: it stuck." A sight which Quentin evidently took great enjoyment in drawing.

Olivier wanted the "Bulletins" to stay in this country, so she sold them to the British Library, and gave the proceeds to Charleston, helping with the upkeep of this important building. But the "Bulletins" have helped keep the old house alive in another way, too: when you read them, Charleston's long dead ghosts live again, reanimated by those who knew them.

The main players

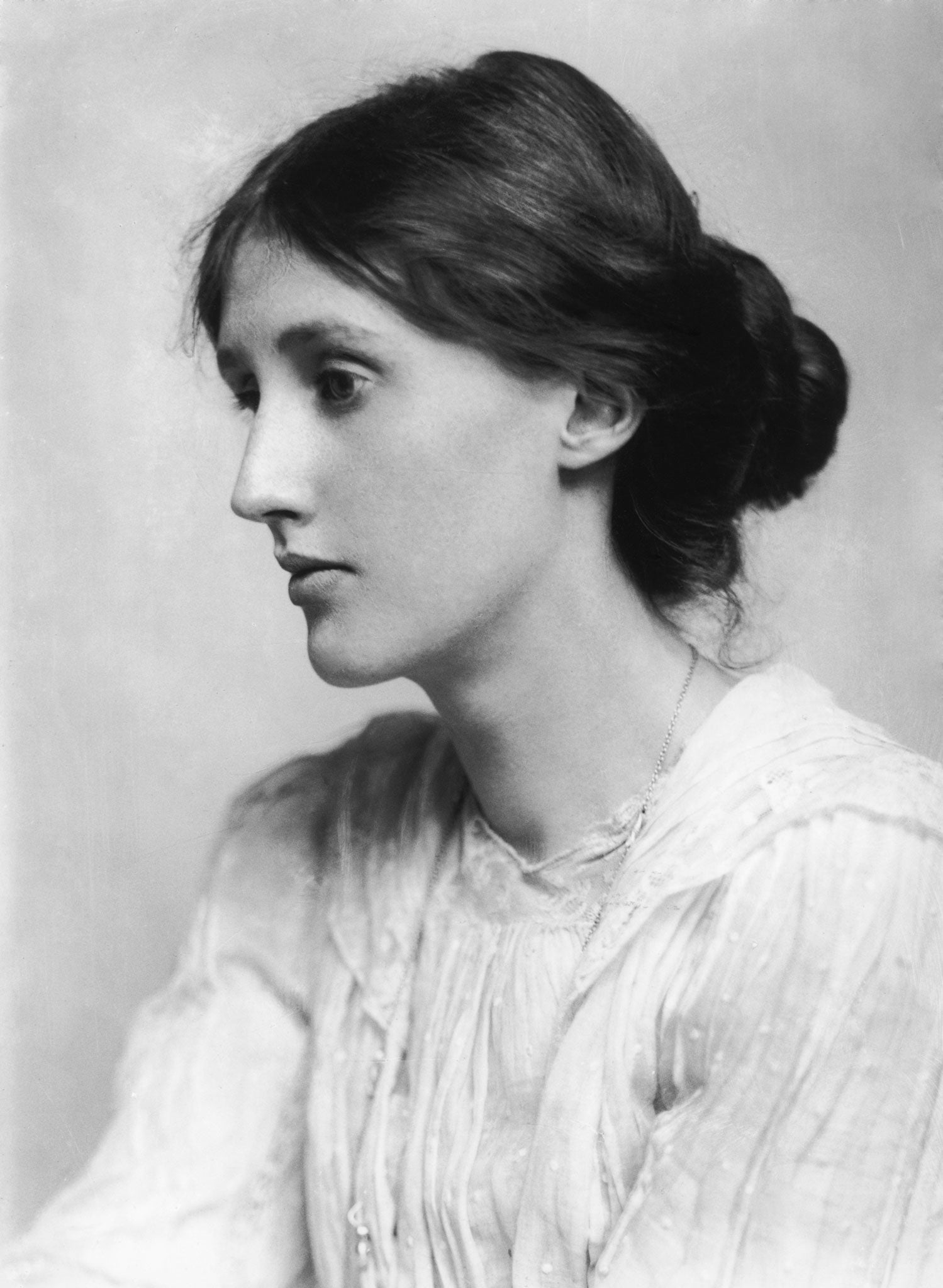

Virginia Woolf

Penned nine novels including Mrs Dalloway and the feminist tract A Room of One's Own, as well as biographies and criticism. Sister of Vanessa Bell. Married Leonard Woolf in 1912, with whom she ran the Hogarth Press. Later became lover of Vita Sackville-West

Vanessa Bell

Artist and interior decorator; co-founder of Omega Workshops, with Roger Fry. Married Clive Bell; they had two sons, Julian and Quentin. Had relationships with Fry, and Duncan Grant; in 1918, Bell and Grant had a daughter, Angelica, who grew up believing Clive Bell to be her father

Leonard Woolf

Met Clive Bell, Lytton Strachey and EM Forster at Cambridge, where they were all members of elite intellectual society the Apostles. Was a civil servant in Sri Lanka; returned to England and married Virginia. Wrote novels, but was better known for his political and Fabian writings

Lytton Strachey

Revivified the form of the biography with Eminent Victorians and Queen Victoria. Although openly gay to friends – with several of whom he had relationships – he also proposed to Virginia Woolf and later lived in a ménage a trois with the painter Dora Carrington and Ralph Partridge

John Maynard Keynes

Worked for the Treasury during the First World War, causing a rift with some pacifist friends. One of the most influential economists of the 20th century, his theories are still pertinent today. Had a relationship with Duncan Grant; married ballet dancer Lydia Lopokova in 1925

Roger Fry

Artist, co-founder of the Omega Workshops and art critic, curator and historian. Became curator of paintings at New York's Metropolitan Museum in 1906. In 1896 married the artist Helen Coombe, who was later committed to a mental institution; partner of Helen Anrep

Duncan Grant

Primarily a painter but also interested in decorative arts. Cousin of Lytton Strachey. Had one child, Angelica, with Bell; also had relationships with Maynard Keynes, Adrian Stephen (Virginia and Vanessa's brother), and David 'Bunny' Garnett – who would later marry his daughter.

The Charleston Festival, featuring dozens of author events, takes place from Friday to 26 May. The house opens to the public every summer, this year until 27 October. For more information, and details of the Centenary Project restoration plans: charleston.org.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments