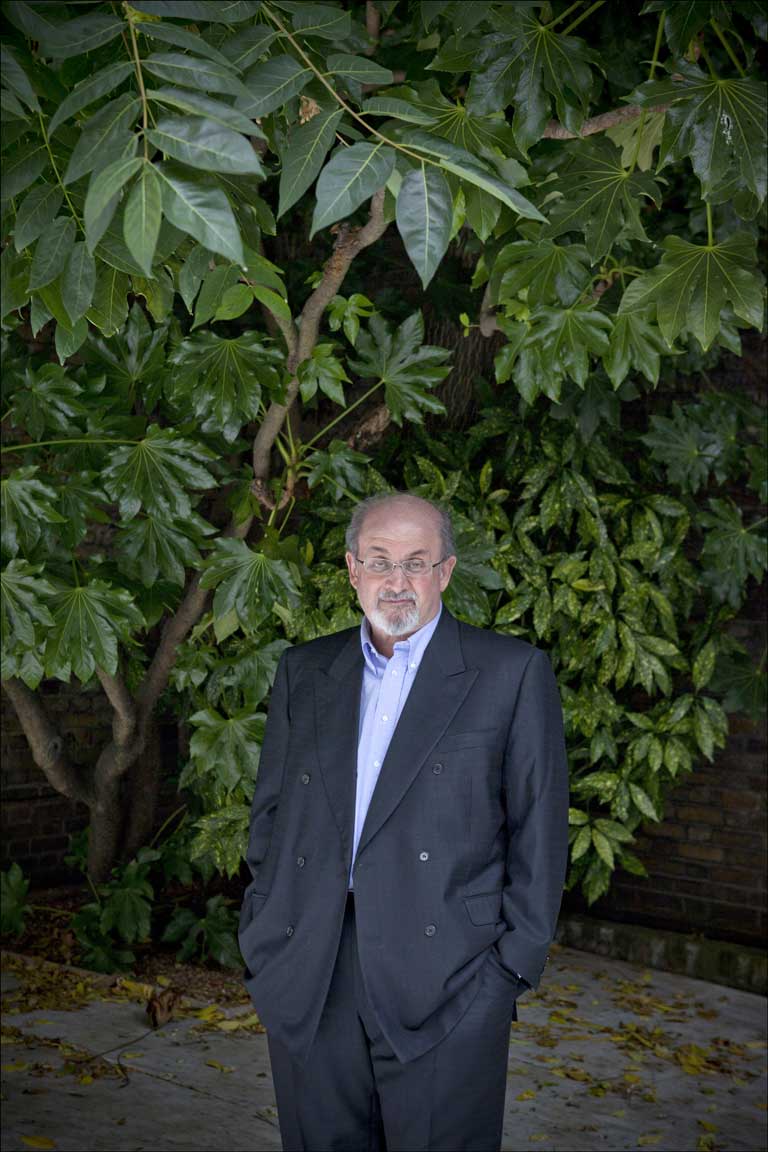

Before the storm: Salman Rushdie has told (almost) all in a frank and zestful memoir

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sir Salman Rushdie began taking notes for his memoir Joseph Anton almost as soon as the Ayatollah Khomeini delivered an "unfunny Valentine" on 14 February 1989. "Within about a week or less of this beginning" – the religious edict, or fatwa, against The Satanic Verses, which called on all Muslims to murder its author and his publishers – its target said to himself, "'You're never going to remember all this. You should start writing it down."

This was a gesture of hope. "I always had a sense, in a way a kind of optimistic sense, that 'One day when it's over I'll write about it'. Which was a way of telling me that one day it would be over." Early in his ordeal, when the novelist had reluctantly left his family home in Islington to begin more than nine years in hiding, he told an interviewer that "I can't write about it until I know the last chapter." Now, he says, "There were moments, depressed moments, when I thought, the last chapter could be so violent that I'm not going to be person telling the story. As depressing was the idea that there might never be a last chapter – that this might just go on and on for ever."

Joseph Anton (Jonathan Cape, £25) is both a precious historical document, and an immersive, page-turning read. Its author compiled it with the help of 120 boxes of personal papers, donated to Emory University in Georgia and then classified over four years. "After that, I had my whole life catalogued – with bar codes." The memoir takes its title from Rushdie's cover identity as an American publisher: a homage to two of his writer-heroes, Conrad and Chekhov.

Names matter in this story. Rushdie himself saw his true identity stolen and grafted on to a detested scapegoat: "It wasn't just that I had to become another person, but that lots of people were reinventing me." Moreover, as he tells us in tender reminiscences of his father Anis, the family tradition of liberal, eclectic, Sufi-tinted Indian Islam led sceptical Anis to change his surname in homage to the great Muslim philosopher of medieval Spain: Ibn Rushd.

Rushdie refers, in the middle of his dark wood of doubt and dread, to the "intolerable eternity" of the death sentence. Then, in 1998 and with Robin Cook as Labour's new foreign secretary pushing hard for progress, the government of Iran agreed not to rescind the dead Ayatollah's ruling (it had no such power) but to take no steps to enforce it. After the 1997 election, the mood "really did change," he recalls. "The energy that came out of Robin Cook and [his deputy] Derek Fatchett was very important in resolving this." So eternity ended. Rushdie has lived entirely in the open for over a decade, mostly in New York, while the Special Branch's Operation Malachite – the unique "prot" squad that guarded him – stood down long ago. He hears from his contact officer from time to time: "It's never been anything serious. But if I need them, I know how to get them."

We talk in his agent's Bloomsbury office. The knighted author, now 65, looks relaxed, speaks warmly and appears younger than in his hidden decade. Normal service resumed? Not quite. On that very day, violent protests against an apparently blasphemous video convulse the Middle East. A key image in Joseph Anton derives from Hitchcock's film The Birds, with the fatwa as "a sort of prologue… the tale of the moment when the first blackbird lands." Now, he says, "We see these storms of birds at the slightest provocation all over the world, chanting their slogans and believing that they can take human life – the lives of people completely unconnected to whatever it is that's supposed to have annoyed them... When it happened to The Satanic Verses, it was kind of an early harbinger of what later became a storm."

Bulky, pacey, intimate, surreal, whipped along by love and scorn, and overflowing with all the tall tales, salty digressions and ripe bit-parts of – well, of a Salman Rushdie novel –Joseph Anton exerts a mesmeric hold with its high-octane storytelling, even as the car-crash fascination of its content grips. It names names. It gives addresses – not just streets, but numbers. We know where he lived, even though he now believes that during those first days of panic and confusion, "I should have said, I'm going home". It annotates his meetings with PMs, presidents and policemen. It pays heartfelt tribute to the sardonic, sympathetic officers of Malachite. So much for the "ungrateful" Rushdie of myth: "They were very friendly relationships, and after all, if you live with someone for a long time, you do get to know a lot about them".

It tells the story of four marriages ("slightly too many marriages"), of two children, and of bereavement (his first wife, Clarissa Luard, died in 1999). It hands out bouquets, to campaigners, champions, sentinels and even tight-lipped London builders: "An enormous number of people did the right thing." And it flings the odd curse too – above all, at liberal appeasers of the zealots' fury: "I think this is a historical mistake of the progressive left. The sense that people who say they're offended have a right to have their offendedness assuaged." For him, free expression ranks as "the right without which all the other rights disappear". It is "the bedrock … If you compromise on that, you lose everything else."

Joseph Anton sits squarely within the canon of Rushdie's books, a swerve into non-fiction but not an outlier. "That was the thing I most wanted for this – that it should feel like one of my books and not like a freak consequence of something that happened to me." Michael Herr, author of the classic Vietnam War reportage Dispatches, crops up among his guardians. With its third-person narration (the writer is "he"), density of circumstantial detail and cracking pace over rich but rough ground, the memoir reminded me of a "non-fiction novel" in the vein of Herr, Tom Wolfe, Hunter S Thompson and Truman Capote. If not In Cold Blood (though of course one translator died; another was gravely injured; his Norwegian publisher survived three bullets in the back), then In Cold Sweat. He agrees, and notes that this chronicle of craziness called for a cool, even voice: "What's happening is so surrealistic, melodramatic, over-the-top... don't over-egg it."

I also ask the cliché question: how did his plight – a decade as a dead man walking – change him? He parries with a "cliché answer: 'Whatever doesn't kill you makes you stronger'." More seriously, "It showed me that I was a more resilient individual that I thought I was. If you had told me the story before it happened and said, 'How do you think you'll deal with that?', I would not have bet on myself to deal with it that way.... But I feel that I was able to come through it, with a lot of help from people who love me. It's information about oneself."

Those "people who love me" – his former wives, apart from the unreconciled second, the American novelist Marianne Wiggins; his sons Zafar and Milan; his sister Sameen; the agents Deborah Rogers, Gillon Aitken and Andrew Wylie; hosts such as Pauline Melville, James Fenton, Margaret Drabble and Liz Calder – kept him alive, and kicking, when the irked state sought to wash its hands. For a start, these friends had to house him. "There was this public idea that I was being accommodated at the expense of the state in government safe houses… But I have never in my life seen a government safe house. It was made very clear to me not only that I could not go home, but that it was up to me to find places to go. One of things I'm most happy about is to have had the chance to talk about how much people helped me."

The Major government proffered only tepid support, with the Foreign Office notably hostile ("that sense I'd made a terrible nuisance of myself and didn't deserve any kind of major effort was there in quite a lot of the civil servants I met"). Other foes dog endeavours to keep his cause afloat. Self-appointed "community leaders" misconstrue the unread The Satanic Verses – with its dream sequence in the mind of a deluded man – and turn co-religionists against him. "One of things that has been very effective, and has probably done the greatest long-term damage... is the campaign inside the Muslim world to demonise me, and to make me out to be an arch-enemy of Islam."

He must also battle his own frailty, especially when – in late 1990, close to despair – he committed his "Great Mistake" and briefly made a profession of faith to pacify his pursuers. At this "bottom of the barrel", he can't draw on the journals because "it's clear, reading them, that the person writing them is in bad mental shape." Yet he knew at once that it was "the stupidest thing I ever did… My body recognised it before my brain. I came out of that meeting literally feeling like throwing up."

In retrospect, "'I see it as a turning-point – not just in this story, but in my life." After that nadir, he chose to fight, embarking on long, weary years of advocacy. Not until 1995, and The Moor's Last Sigh, did Rushdie the novelist of crossed borders and blended cultures return. What's remarkable is that the generous, exuberant post-fatwa novels of mingling and migration read so much as natural extensions of a line that stretches back to Midnight's Children. "One of the things I'm proud of is that early on, I told myself that's what I should try to do. There are these ... elephant-traps: I could have been frightened into writing inoffensive little timid books, or distracted into writing embittered, angry books. And both of those are destruction for me."

Joseph Anton not only reveals political secrets, but personal ones. Its frankness about the strain of marriage on virtual death-row – to Wiggins, then to the editor Elizabeth West, and in the aftermath to actress-presenter Padma Lakshmi – will have jaws dropping. Apart from Wiggins, the ex-wives read and, after amendments, consented to these passages. As for his first marriage, and the woman whose beloved shadow falls across the book, "Clarissa wasn't around to read it, but Zafar [their son] read it, and certainly if he had felt awkward with anything about his mother, I would have respected that. But he liked it very much... With the exception of Marianne, I'm on perfectly good terms with everyone I've been closely connected to, and this isn't going to come to them as a surprise."

There it is," Rushdie concludes. "I can't be more honest, more open, more detailed, than this. Whatever people make of the book, I hope that they will see that it's written by somebody who's really trying to tell the truth – who is not being defensive or revisionist." Currently, he plots a return to fiction, and "can't think of anything nicer than spending a couple of years quietly in a room trying to make up a story." But the moving image has always lured Rushdie - a walk-on actor in Bridget Jones's Diary, author of a monograph on The Wizard of Oz, and with Deepa Mehta's film of Midnight's Children, which he both wrote and narrated, due to open soon. He has a TV project afoot in the US, a "paranoid politics-slash-science fiction series called The Next People, for Showtime". Now, "paranoid politics-slash-science fiction" might strike the reader as a thumbnail sketch of Rushdie's bizarre, afflicted yet oddly exhilarating journey through Joseph Anton. As the blackbirds flock again, let's hope that such a weird hybrid stays firmly in the studio.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments