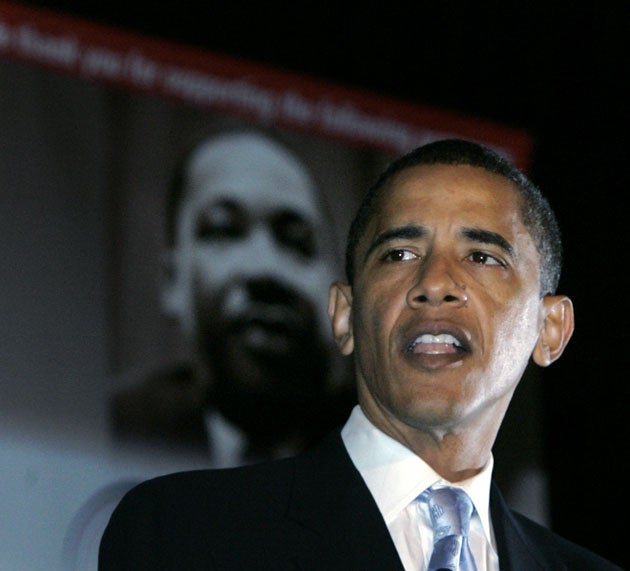

Barack Obama: The words of a dream

Barack Obama, writer and orator, has deep roots in a tradition of eloquence that dates back to the age of slavery. As he prepares to accept the Democratic nomination in Denver next week, Candace Allen traces his literary heritage of memoir and testimony

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Next Thursday, in a major departure from tradition, Illinois Senator Barack Obama will deliver his speech accepting the presidential nomination of the Democratic Party not from within the Party's convention space but before a crowd of 75,000 at Denver's Mile High football stadium and, in this era of expanded technological capabilities, a world-wide audience of millions.

This will happen 45 years to the day after the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom that culminated in Dr Martin Luther King, Jr.'s epochal evocation of a dream. The broad outlines for the Denver convention schedule were finalised long before anyone could have conceived that an African-American candidate would be baking such history, let alone one who shared with MLK, Jr. so eloquent and elegant a mastery of the word, written and then delivered. The emergence of Obama is often thought to be without precedent, but he is part of a tradition stretching back over 150 years.

Only 34 on the afternoon he outlined his dream in 1963, King had been a recognised leader of the Civil Rights movement since the age of 26, when he took the helm of Montgomery, Alabama Bus Boycott. King's life moved at a lightning pace during his 13 years in the nation's spotlight before being struck down by an assassin's bullet in April 1968. There may have been requests for him to record his life story, but there was no time. The momentum of the movement allowed few moments for respite and most reflection was in service of its cause. King's written legacy is his speeches: inspirational, thoughtful, influenced by a wide range of philosophy and activism. What kind of memoir could such a mind and soul have produced? Our loss.

At 26, Barack Obama was engaged in community organisation and activism on the hard streets of Chicago's South Side. His first flicker on the screen of national consciousness occurred at 29, when he was elected the first African-American editor in the then 103-year history of the Harvard Law Review. In the first half of the 19th century, fugitive slave narratives written by the narrator him- or herself became a major feature of the abolitionist movement. At this point, in the same pattern, Obama was asked: "Tell us how you got here. Tell us who you are. Tell us how someone like you came to penetrate our world." The result, in 1995, was his memoir, Dreams from my Father.

The most famous of these slave accounts was the Narrative of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself in 1845, when Douglass was about 23 (he never knew his birth date). It was followed by the Narrative of William Wells Brown, Fugitive Slave in 1847 when Brown was approximately 33. Both Douglass and Brown were products of slave mothers and unknown white fathers. Both had to struggle for literacy, but their slave lives were very different: that of Douglass characterised by the worst kind of punishment, humiliations and whippings, while Brown had gentler owners and was able to trickster his way to freedom.

Both Douglass and Brown had been eloquent orators on the abolitionist circuit for years before being commissioned to record their tales. The resultant narratives mirror the differences in their experiences and temperaments. Brown's was more modest, written in a plain style with very little self-reflection, while that of Douglass was fiery, as electrifying as he was as an orator, as it related one slave's understanding of himself as a human being with human rights.

Brown never wrote autobiography again, going on to publish the first black-written American novel, Clotel, or The President's Daughter (1853), the first travel writing (Three Years in Europe in 1852) and the first drama (The Escape or Leap to Freedom in 1858). Douglass dedicated his life to activism. With his own life as the object lesson, he wrote two more books of autobiography, each more reflective than the last, in 1855 and 1892.

In a world in which very few blacks had access to books, where slave literacy was illegal and punishable by severe whipping and even death, the overwhelming audience for the 19th-century slave narratives was white. This began to change with the slow and often limited spread of education for the freedmen. But for decades, the readership, let alone the publishers, of such books would remain overwhelmingly white and keyed to the white disposition.

Naturally, in the 150 years between the appearance of Dreams from My Father and the Douglass/Brown narratives, the intended audience has greatly diversified and the white temperament become somewhat more flexible. But it was Obama himself who decided to move from the "explain yourself to us" initial commission from his publisher. Instead, he wrote, "through exploration and rumination perhaps I can explain myself to myself, chart my route to the identity I understand and establish for myself, and thereby, perhaps, have a message for others".

Historically, such psychological exploration – almost always within the context of "how do I place myself within this treacherous terrain of race?" – appeared first in fiction: from Iola Leroy, Frances Harper's tale of the triumphant claiming of black heritage by a mulatto woman in 1892, to James Weldon Johnson's The Autobiography of an ex-Coloured Man in 1912, through to Richard Wright's Native Son in 1940 and Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man in 1952. Along the way mature, ruminative memoirs appeared by Douglass, Weldon Johnson, Langston Hughes and Claude McKay, among others. But identity- fixated African-American youthful memoir didn't manifest its panoply of possibility until the first essays of James Baldwin. Baldwin never wrote a formal long memoir, operating instead from the stance that "all art is a kind of confession". But, from his first essays until his death in 1987 at 63, his prism was his own experience, refracted through a formidable erudition.

Like many of his antecedents, like Douglass who was whipped for attempting to learn, like the Jamaican-born Harlem Renaissance writer Claude McKay, Baldwin sought through books an escape from harsh realities and the indication of a path to a less degraded way of life. This desperation for learning, this search for explanation and salvation via the word, has not, of course, been restricted to those of the black race. But it has often characterised the lives of outsiders who later excel - the essentially self-taught Abraham Lincoln, for example, who struggled for both knowledge and wisdom from a position of deprivation and never took them for granted.

Barack Obama's early life wasn't plagued by the extremes of pain or poverty of many of those towards whom he looked for guidance; but after some undistinguished academic application and mild adolescent nihilism, a good amount of the guidance Obama sought, he found on the printed page. In Dreams, he relates that he couldn't find the answers he sought in Wright, Hughes, Ellison, Baldwin and WEB DuBois, characterised as they were by ultimate exile, disappointment and even self-contempt.

To the teenage Obama, only Malcolm X's repeated acts of self-creation, as related in his dictated autobiography, made redemptive sense, especially after Malcolm's abandonment of The Nation of Islam's more racist precepts. Malcolm's self-creation included self-educated erudition. Though I doubt that he would compare himself to either Malcolm X or Martin Luther King, like them Obama found his way to himself and to political activism via the word. Like them, he has combined that mastery with inspirational dynamism. It will be interesting to see if his example might also inspire a return to the written word among a generation that has essentially eschewed its necessity. Whether or not Barack Obama is elected President of the United States, the nature of American politics has been transformed by his candidacy – which developed from his relationship to the word.

Candace Allen's novel 'Valaida' is published by Virago

Memoirs of hope

Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass

Born a slave in Maryland in 1818, subject to a brutal master, Douglass escaped to freedom in 1838 and served as a spearhead of the abolitionist movement. His autobiography (1845) became near-holy scripture for the cause.

The Souls Of Black Folk

W.E.B. Du Bois

In 1903. Du Bois took the record of Black American life into new territory with a blend of memoir, history and psychology, asserting: "the problem of the 20th century is the problem of the colour line". He explored the psychic and cultural legacy of slavery.

Black Boy

Richard Wright

In his 1945 autobiography, the author of 'Native Son' shows how religion, family and racial pressures converge in a shocking account of a Mississippi upbringing in the Jim Crow era. His rejection of faith and passion for literature signal an agonising separation from roots.

Notes Of A Native Son

James Baldwin

Baldwin enriched all the essays in this first non-fiction book with glimpses of his background. From his love-hate for his father to memories of segregation and a quest for liberation in Paris, his journeys as an African American, writer and radical entwine.

The Autobiography Of Malcolm X

Malcolm Little from Nebraska became the fieriest, most feared of 1960s Black activists. After his jail conversion, the former criminal campaigned for the separatist Nation of Islam. He abandoning its extremism for mainstream Muslim belief before his assassination in 1965. This testament was ghosted by Alex Haley, later of 'Roots' fame.

I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings

Maya Angelou

Before she became Oprah Winfrey's mentor, the former dancer had, in 1969, published this memoir of hard times and high ideals in 1930s and 1940s Arkansas. Abuse, hardship and racism never silence the note of hope and aspiration that carried Angelou through many future memoirs and made her a beloved American icon.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments