Baileys Prize 2015: Why we sadly still need women-only book prizes

Why does having a vagina still matter in publishing? Because women's voices are not being heard

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

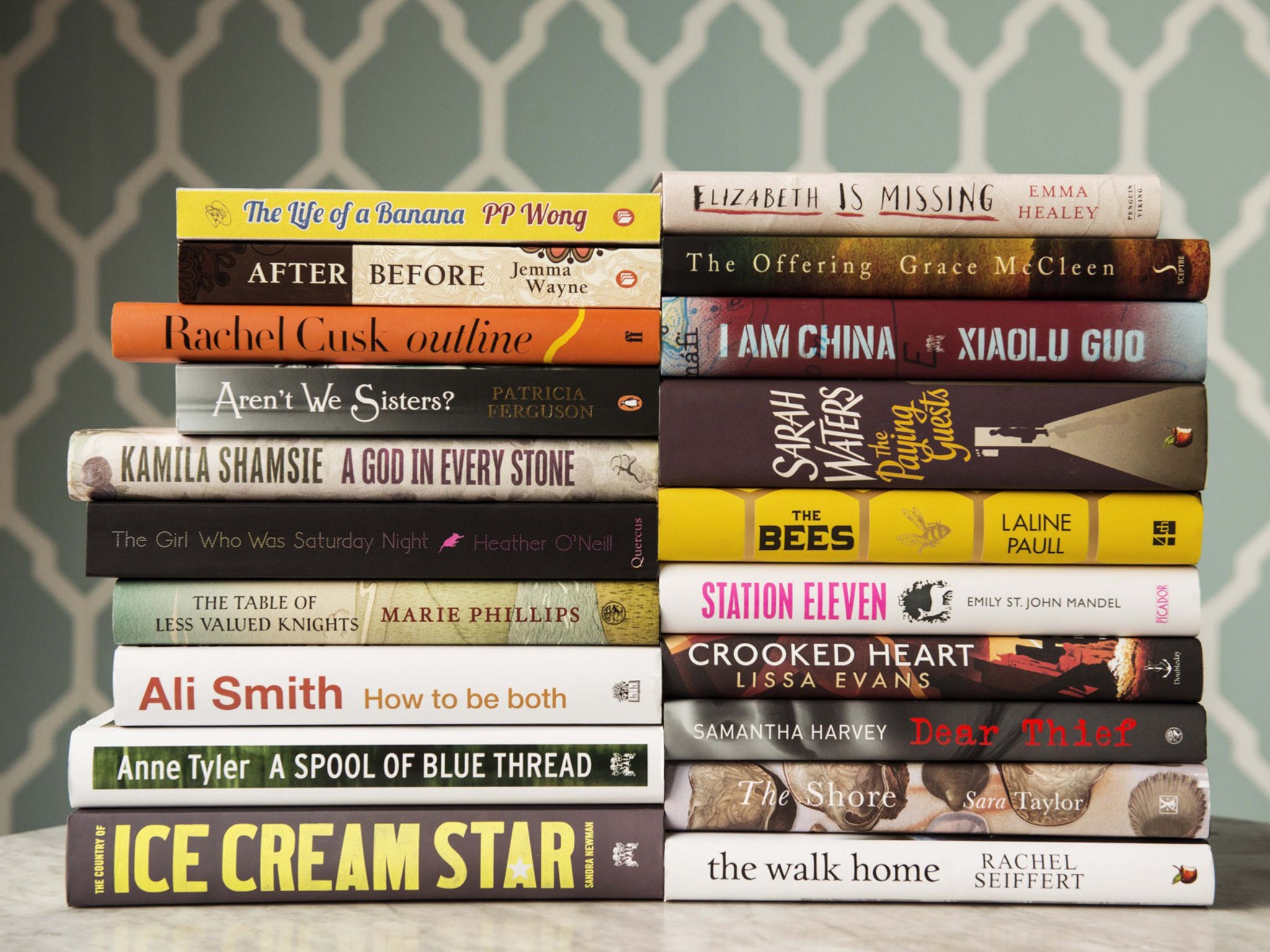

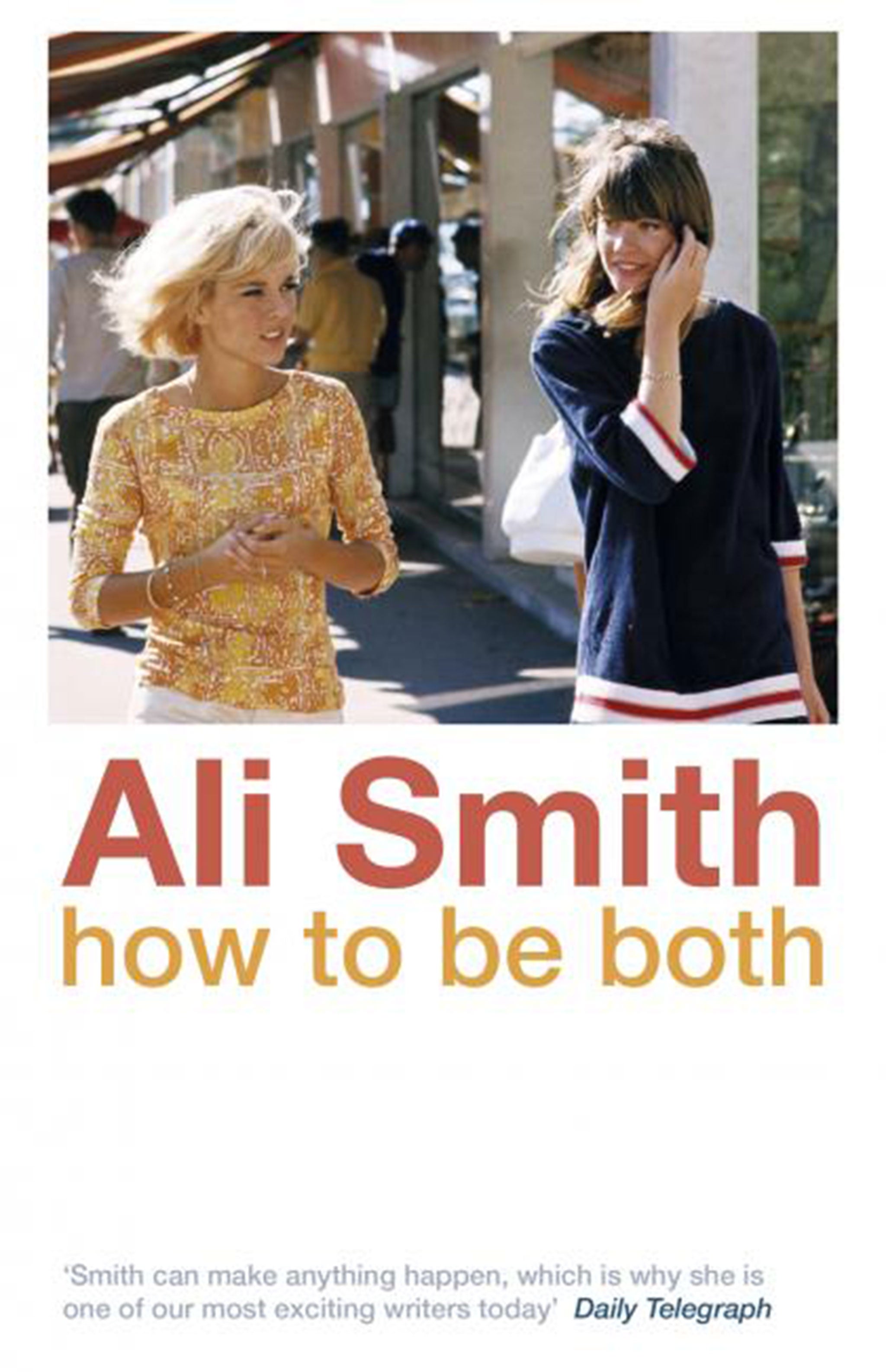

Your support makes all the difference.The Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction (formerly Orange) was last night awarded to one of the UK's best writers, Ali Smith, for her novel How To Be Both.

This year's shortlist was made up of a crop of writers so established (think Sarah Waters) and commercially successful that the fact that each of them has a vagina is probably be by the by for most of their readers.

But despite women being the main consumers of books, both reading and buying more fiction than our male friends and relations, as well as writing more novels, we continue to be sidelined and, despite our equal or majority (in population terms) status in the world, treated as a minority and a rarity by the literary establishment.

The likes of Hilary Mantel might have more awards than her, er, Mantel can handle, but we still have a way to go before women’s voices are deemed as interesting, acceptable and readable as men’s.

Books about women don’t win awards

“It’s hard to escape the conclusion that, when it comes to literary prizes, the more prestigious, influential and financially remunerative the award, the less likely the winner is to write about grown women,” critically acclaimed author Nicola Griffith wrote in a blog post this week.

“Either this means that women writers are self-censoring, or those who judge literary worthiness find women frightening, distasteful, or boring. Certainly the results argue for women’s perspectives being considered uninteresting or unworthy. Women seem to have literary cooties,” Griffith continued.

Analysis she conducted of the last 15 years of winners of six major literary awards found that women’s voices were not being heard or recognised by the literary establishment. “If half the adults in our culture have no voice, half the world’s experience is not being learnt from. Humanity is only half what we could be."

Only two Man Booker-winning novels had been written by women from a female perspective between 2000 and 2014, compared to nine Booker winners written by men about men or boys. In that time no novel by a man about women had won the Booker, while on three occasions female authors had won the award by writing from a male perspective.

Pink fluffy covers

Plenty of excellent works of fiction by women with clear and forthright female perspectives are sold by publishers in the(arguably) wholly pejorative genre of “chick-lit”. Whatever happened to romance fiction? Or a classic love story with, you know, characters of both sexes. Wait, you mean a man might actually read a story with a girl in it? Frankly it’s patronising to both genders to assume they wouldn’t.

By putting pink dust jackets on novels publishers are admitting that men don’t buy as many books as women and are assuming that they do judge them by their covers (who doesn’t?). But selling books as completely limited to one half of the population comes with an implicit denigration/criticism and assumes that men aren’t interested in women’s stories. The fact that JK Rowling is not known worldwide as Joanna Rowling was so that males weren’t put off by seeing her name on the cover of Harry Potter. How many hours of reading enjoyment have those clever publishers provided boys with via that canny marketing move? For something with the word-of-mouth traction of the Potter franchise surely it would have been as popular whether it had Hermione’s face on it not Harry’s.

“I write women’s fiction,” Picoult told The Telegraph last year. “And women’s fiction doesn’t mean that’s your audience. Unfortunately, it means you have lady parts.” She also claims the publishing industry ignores big issues in her books to put a girly spin on them. “When people call The Storyteller [which is about a former Nazi SS guard] chick-lit, I actually break up laughing. Because that is the worst, most depressing chick-lit ever,” she says.

Women love books and totally dominate the publishing industry

There is statistical evidence that women not only read more novels than men, attend more book clubs than men, buy more books than men, use libraries more than men, and write more works of fiction than men…

Yet between 2000 and 2014 the Man Booker Prize was won by nine books by men about men or boys, three books by women about men or boys, two books by women about women or girls, and one book by a woman writer about both.

Kate Mosse, who co-founded the Women’s Prize for Fiction in the mid-Nineties, has been told on numerous occasions by booksellers including giant of the high street Waterstones that “[the Baileys] sells books like no other prize”.

Smart, accomplished women are everywhere in the publishing business too – with the biggest publishing houses being run from the bottom upwards by the female of the species. Yet a recent report by the Bookseller found that despite the fact that 80 per cent of staff at Pan Macmillan (one of the largest publishers in the UK) are female there are just four women on the company’s board, five divisions that are run by female bosses and six division heads who are not men.

Clare Smith, publishing director at Little, Brown and Abacus, told the industry magazine: “It is hard to ignore the fact that publishing is very female-dominated to a certain level, and that beyond that level, the balance switches the other way.“

But female bosses are stealthily being ousted from the top jobs

Helen Fraser, the former Penguin managing director, retired in 2009 with her job going to a man; Gail Rebuck, chair of Penguin Random House’s UK operations, stepped down from the day-to-day running of the company two years ago; Victoria Barnsley, who founded the Fourth Estate publishing house, was replaced as CEO of HarperCollins by Charlie Redmayne; Ursula Mackenzie recently announced she is stepping down as Little, Brown chief executive to be replaced by David Shelley.

Industry experct Danuta Kean wrote a piece in Mslexia magazine claiming that there has been a “silent takeover by men of the top jobs” in publishing. She writes: “To some extent the departure of these women reflects a generational shift. All fought their way to the top in the 1980s and all are now of retirement age. But, given the huge workforce of women at every other level in the publishing industry, why aren’t they being replaced by women?”

The media are guilty too

In the London Review of Books, 73 per cent of the books reviewed are by male authors and just 27 per cent are by women, according to the Vida count 2012. While in the TLS, 75 per cent of books reviewed are by men and 25 per cent by women. In the New Yorker that year just 58 books by women were reviewed compared to 138 books by men.

Mosse has previously said that when she started the prize in 1996 around 60 per cent of novels published were by women, and roughly 70 per cent of novels bought were by women. But fewer than 10 per cent of books that ever made it to leading prize shortlists were by women “and in reviewing it was much worse”.

Why women want a women-only prize

“Part of the pleasure of being on last year's Baileys short-list was the relief of being able to just talk about my work rather than being continually obliged to quantify the relationship of my gender to my work and vice versa. Until that experience becomes as passé for female writers as it is for male ones, the need for female-only awards will remain, “ last year’s Baileys winner winner Eimear McBride told The Independent.

“This change would require a major recalibration of the industry's, and society's attitude towards the female experience and expressions thereof. I hope that day will come but it's certainly not here yet.”

Shami Chakrabarti, director of Liberty and a Baileys prize judge, said: “Often when a woman wins a big prize she has written about male characters, so this is yet another vindication of the importance of the Baileys Prize. Women are entitled to see themselves reflected in these stories.

“I have always been of the view that story telling changes the world – more than journalism, polemic, great speeches or even legislation. So given that gender injustice is in my view the biggest injustice on the planet, it is very important that women’s stories are told.”

Stella Duffy, who is in the process of launching the Women’s Equality Party with her fellow writer Kathy Lette and the radio and television presenter Sandi Toksvig , said: “Of course women’s voices aren’t being heard. This is entirely my experience. When I was writing The Room of Lost Things, with two male protagonists, I knew that even though it wasn’t markedly better than my other work, but it would be taken more seriously and get more attention than my other work.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments