Alain de Botton: the idea of home

For a word that carries intimate associations of sanctuary and relief, "home" seems riddled with a remarkable number of incoherencies and paradoxes. To begin with, home is almost always a place that we don't appreciate when we are there. Its omnipresence makes it invisible. Think about how differently we approach "abroad" as opposed to "at home". We approach new places with humility. We carry with us no rigid ideas about what is interesting. We irritate locals because we stand in traffic islands and narrow streets and admire what they take to be meaningless details. We risk getting run over because we are intrigued by the roof of a government building or an inscription on a wall. We find a supermarket or hairdresser unusually fascinating. We dwell at length on the layout of a menu or the clothes of the presenters on the evening news. We are alive to the layers of history beneath the present and take notes and photographs.

Home on the other hand finds us more settled in our expectations. We feel assured that we have discovered everything interesting about our house and our neighbourhood, primarily by virtue of having lived there a long time. It seems inconceivable that there could be anything new to find in a place which we have been living in for a decade or more. We become habituated and therefore blind. But if we leave home and end up in an alien and frightening environment, how soon we remember home – and with what fondness! The only time we really "see" our homes and recognise their value is when we aren't in them – just as we might only truly feel the love we have declared for our spouses when they are away from us, or when they are dying. Deprivation quickly drives us into a process of appreciation – suggesting that one way to better appreciate something is to regularly rehearse its loss.

To all this we can add the thought that our need for a home arises out of a vulnerability and a lack of solid identity. Our sensitivity to our surroundings may be traced back to a troubling feature of human psychology: to the way we harbour within us many different selves, not all of which feel equally like "us", so much so that in certain moods, we can complain of having come adrift from what we judge to be our true selves.

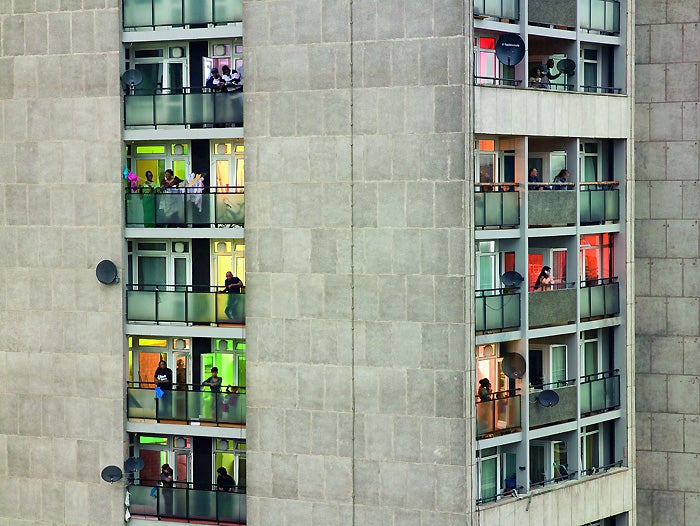

Unfortunately, the self we miss at such moments, the elusively authentic, creative and spontaneous side of our character, is not ours to summon at will. Our access to it is, to a humbling extent, determined by the places we happen to be in. In a hotel room strangled by three motorways, or in a wasteland of run-down tower blocks, our optimism and sense of purpose are liable to drain away. We may start to forget that we ever had ambitions or reasons to feel spirited and hopeful. We depend on our surroundings obliquely to embody the moods and ideas we respect and then to remind us of them. We look to our buildings to hold us, like a kind of psychological mould, to a helpful vision of ourselves. We arrange around us material forms which communicate to us what we need – but are at constant risk of forgetting we need – within. We turn to wallpaper, benches, paintings and streets to stanch the disappearance of our true selves. In turn, those places whose outlook matches and legitimises our own, we tend to honour with the term "home".

Our homes do not have to offer us permanent occupancy or store our clothes to merit the name. Home can be an airport or a library, a garden or a hotel. Our love of home is in turn an acknowledgement of the degree to which our identity is not self-determined. We need a home in the psychological sense as much as we need one in the physical: to compensate for a vulnerability. We need a refuge to shore up our states of mind, because so much of the world is opposed to our allegiances. We need our rooms to align us to desirable versions of ourselves and to keep alive the important, evanescent sides of us.

It is the world's great religions that have perhaps given most thought to the role played by the environment in determining identity and so – while seldom constructing places where we might fall asleep – have shown the greatest sympathy for our need for a home. The very principle of religious architecture has its origins in the notion that where we are critically determines what we are able to believe in. To defenders of religious architecture, however convinced we are at an intellectual level of our commitments to a creed, we will only remain reliably devoted to it when it is continually affirmed by our buildings. In danger of being corrupted by our passions and led astray by the commerce and chatter of our societies, we require places where the values outside of us encourage and enforce the aspirations within us.

Without honouring any gods, a piece of domestic architecture, no less than a mosque or a chapel, can assist us in the commemoration of our genuine selves. Imagine being able to return at the close of each day to a beautiful home. Our working routines may be frantic and compromised, dense with meetings, insincere handshakes, small talk and bureaucracy. We may say things we don't believe in to win over our colleagues and feel ourselves becoming envious and excited in relation to goals we don't essentially care for. But, finally, on our own, looking out of the hall window on to the garden and the gathering darkness, we can slowly resume contact with a more authentic self, who was there waiting in the wings for us to end our performance. Our submerged playful sides will derive encouragement from the painted flowers on either side of the door. The value of gentleness will be confirmed by the delicate folds of the curtains. Our interest in a modest, tender-hearted kind of happiness will be fostered by the unpretentious raw wooden floor boards. The materials around us will speak to us of the highest hopes we have for ourselves. In this setting, we can come close to a state of mind marked by integrity and vitality. We can feel inwardly liberated. We can, in a profound sense, return home.

We value certain buildings for their ability to rebalance our misshapen natures and encourage emotions which our predominant commitments force us to sacrifice. Feelings of competitiveness, envy, and aggression hardly need elaboration, but feelings of humility amid an immense and sublime universe, of a desire for calm at the onset of evening or of an aspiration for gravity and kindness – these form no correspondingly reliable part of our inner landscape, a rueful absence which may explain our wish to bind such emotions to the fabric of our homes. A beautiful home can arrest transient and timid inclinations, amplify and solidify them, and thereby grant us more permanent access to a range of emotional textures which we might otherwise have experienced only accidentally and occasionally.

There need be nothing preternaturally sweet or homespun about the moods embodied in domestic spaces. They can speak to us of the sombre as readily as they can of the gentle. There is no necessary connection between the concepts of home and of prettiness. One can feel at home in a place which is very unhomely – such as a diner or a motorway café with others similarly lost in thought, similarly distanced from society: a common isolation with the beneficial effect of lessening the oppressive sense within a person that they are alone in being alone. The very lack of domesticity, the bright lights and anonymous furniture can be a relief from what may be the false comforts of a so-called home. What we call a home is merely any place that succeeds in making more consistently available to us the important truths which the wider world ignores, or which our distracted and irresolute selves have trouble holding on to.

Alain de Botton is the author of 'The Consolations of Philosophy' and 'The Architecture of Happiness', among other works

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks