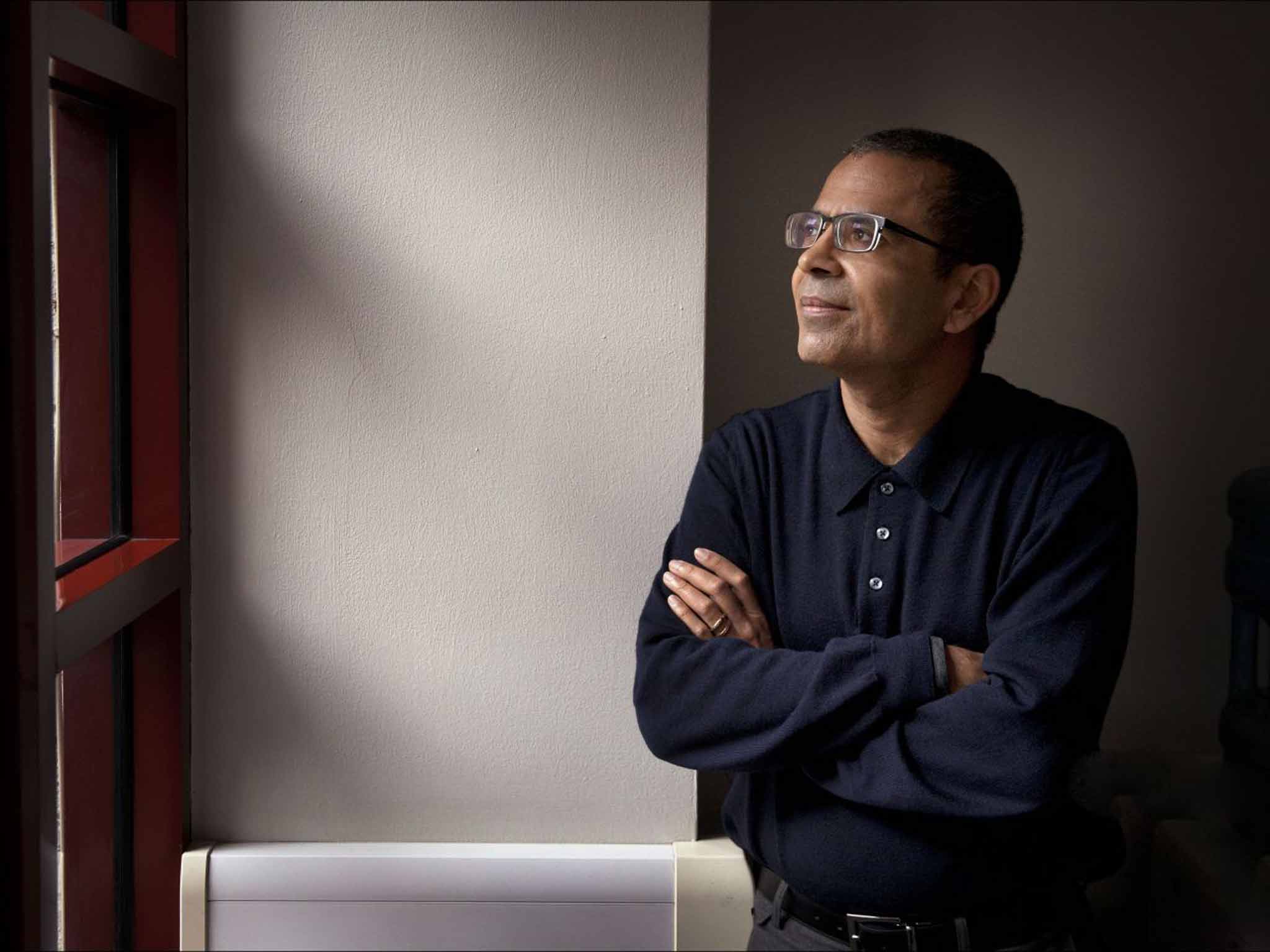

Akhil Sharma on his Folio Prize winner 'Family Life': A triumph plucked from despair

A tragedy moved Akhil Sharma to write 'Family Life' so the prize was bittersweet, he tells Nick Clark

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Few authors, after receiving a prestigious literary prize, wish they had not written the winning book. But Akhil Sharma, newly crowned winner of the Folio Prize, is no ordinary author – and the traumatic 13-year process of writing his acclaimed novel, he said, has left him "damaged".

Family Life, the prize-winning work, is an intensely personal novel which fictionalises his family's move to the US – a move that was shattered by a devastating tragedy. He started writing at the age of 30, and now, at 43, and on the night of the award, said that the effort had "shattered my youth".

Sharma was born in Delhi and moved with his family to America at the age of eight. Two years later, his brother Anup, who was then 14, dived into a pool and hit his head on the bottom. He was underwater, stunned, for three minutes, and was left with severe brain damage when they pulled him out.

The first response – after William Fiennes, chair of the judges for this year's Folio Prize, read out Sharma's name – was unexpected. "It was shame," he said, explaining that he felt he had received "too much luck" while his brother had none. With time to reflect on his victory, Sharma said that the shame had "gone away. What is left is anxiety about what it means."

Reliving the story for his novel and carrying it around for 13 years was "damaging", he told The Independent. "Things occur now and I panic much more than I would have before I started writing this book. All the trauma of writing it comes back." The author then echoed the sentiment from the previous night's press conference: "I'm proud of the book; I just wish I hadn't been the one to write it."

Sharma said he had written all his life – but after attending Princeton University and then Harvard Law School, he joined the Wall Street investment bank Salomon Smith Barney. From the start, he loathed the banking culture and lifestyle. "I hated it because I could not care less about the industry; yet it was also enormously stressful and demanding."

He had kept up his writing – and during his time at the firm his first novel, An Obedient Father, was published. It had taken nine years to write and won the PEN/Hemingway Award.

After three and a half years, Sharma left Wall Street. "I just couldn't stand it," he says, but writing brought its own challenges: "I didn't think it would be easy, I just didn't think it would be this hard." Family Life, his second novel, was, by his own admission, nine years overdue – and the process "felt like chewing stones".

The protagonist, Ajay, is closely modelled on the author, and the descriptions of his initial wonder at arriving in America at the age of eight reflects Sharma's own. The novel turns tragic, yet "My own life was so much darker," says Sharma. "I wanted to preserve certain things, but knew there was stuff I couldn't put in without driving the reader away. All the physical illness."

His brother remained alive for 30 years, 28 of which were in his parents' house, but he died three years ago. "I wanted him back, no matter how sick he was, I wanted him back. I don't care about the misery, I just wanted him there."

While he is unsure if his mother has read the book, and sure that his father has not, he did consult with them. "I see this as a love song to my parents and my brother," he says. "They endured the unendurable. But everyone will have to go through it, people get sick and die, and it is unendurable. And then you'll endure it.

"Initially I wanted to write it because it was an interesting story. It became really hard, but part of the reason I stuck with it was because I wanted to memorialise my family," he says. "I don't want what happened to my brother to be forgotten."

He experimented with different styles, voices and even narrators, as "I didn't really know how to do this book." Trying to apply the same techniques as the first book failed completely – and he turned to admired writers such as Chekhov for guidance.

Then it clicked. "After spending all this time looking at my parent's suffering and misery, I had to come up with a sympathy and understanding of it. When I did, it became possible to come up with a different style."

Sharma was not writing any other fiction during the first eight years of writing the book, and was supported by his wife, who he met in law school. Yet the collapse of her firm, Lehman Brothers, in 2008 meant that Sharma had to find a new job, and he started teaching creative writing at Rutgers University-Newark, where he is still assistant professor.

It had a positive effect on his writing. "First, getting a pay cheque made me much less anxious and meant that I could concentrate on writing more fully," he says, adding that it made him more confident and able to see different perspectives on his own writing.

It was finally published last year. Despite the plaudits and the prizes, Sharma has not found closure after finishing the work. "I don't know what closure means in this case. There's no closure in life; instead I ask, 'did I do something useful with this experience?'" He dedicated the book to carers – and said that he was hugely proud that it was being taught in medical schools around the US. He has also started lecturing to medical students on dealing with patients and families in long-term caregiving.

Despite a string of awards to add to the Folio, and being named on the list of Granta's Best of Young American Novelists in 2007, the doubts persist: "Even now, I have a hard time thinking that I'm a writer," Sharma says. "With fiction, you have to reinvent everything. I was able to do these two books, but I never know if I can do the next thing."

After the dust had settled from the award ceremony yesterday morning, Sharma, standing in a sunny courtyard, said that he realised that the £40,000 cheque meant that he could go to Italy, possibly to the Umbrian countryside. "It's the sudden relief of having money, and with any excuse, I will go to Italy." The only other extravagance he has thought to spend his winnings on so far is a tailor-made overcoat from India.

Sharma is currently working on a collection of short stories which should be released later this year. He said that after the difficulty of the two novels, he had taken a conscious decision to shift to the shorter form – and writes five hours a day, timed with a stopwatch. "I don't have the emotion in me to write another novel – well, for now at least."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments