A song of praise for the poet in peril

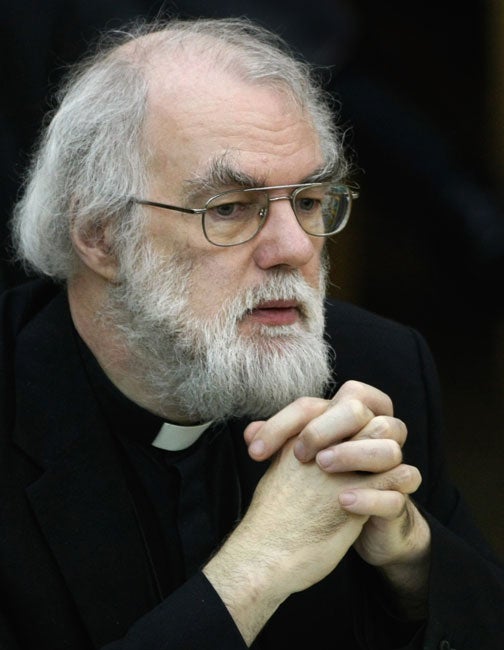

In addition to the spectrum of gifts that only stops short at a talent for unifying leadership, Rowan Williams is a poet - not a scribbler of holy doggerel, but a serious writer who aspires to (and achieves) the real thing.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Yesterday, the Queen hosted a garden party for Dr Rowan Williams and the 650-odd Anglican bishops who still (as they turned up to the Lambeth Conference) acknowledge his authority.

If Her Majesty felt the need for a soothing topic of conversation with the embattled Archbishop of Canterbury, she might have chatted about poetry. In addition to the spectrum of gifts that only stops short at a talent for unifying leadership, Williams is a poet – not a scribbler of holy doggerel, but a serious writer who aspires to (and achieves) the real thing. When a selection of his work came out on his accession, I read it with a tease in mind and ended up feeling like the parson's flock in Goldsmith's Deserted Village: "and fools, who came to scoff, remained to pray".

Except that readers of the Archbishop's poetry will seldom wish to fall on their knees. He hardly ever writes straightforward devotional verse, but knotted lyrics of personal struggle – sometimes with an overtly religious theme, pretty often not – which pay more heed to striving than arriving. In his new collection Headwaters (Perpetua Press, £9), a strenuous sequence compares Bach's St Matthew Passion to a storm-tossed sea voyage. It evokes "the long grey/ leaving of the day that never reaches night". Except for the odd genre piece (a meditation on Piero della Francesco's "Resurrection"; a Christmas carol), Williams writes from the troubled and twilit middle of the journey. And even his carol chillingly fixes not on manger and magi but on the Massacre of the Innocents: "Frost scratching at the door,/ Blood has spilled across the floor...".

Naturally, the scholar-primate nods to his great forerunners in the Anglican literary tradition, from the Dean of St Paul's (John Donne) to the Churchwarden of St Stephen's, Gloucester Road (TS Eliot) – with a special affinity, perhaps, for fellow Welsh poets, from Henry Vaughan to RS Thomas. I loved his timely translation of D Gwennalt Jones's "Sin", with its scorn for all pomp and position: "drop the reviews, awards/ Certificates, stand naked in your sty,/ A little carnivore, clothed in dried turds".

Translation seems to give Williams a licence to stray from his Anglican via media in poetry: a moderate modernist who embraces tradition. His versions of the Russian poet Inna Lisnianskaya have a special bounce and bite. In "At the Jaffa Gate", her aged lover buttonholes Solomon and, saluting the power of words for good or ill (as many of his own poems do), recalls that "It was the songs that turned me on, not just the hard flesh". As a sonnet on Much Ado About Nothing (part of a Shakespearean sequence) has it, "paper cuts can kill".

Many of these pieces would grace any volume by a poet who did not also hold down the second-most taxing post in our public life. They can stand, and sing, by themselves, although this week it's hard not to feel the breath of allegory in a reference to a sheepdog trial: "you need/ to chase the flesheaters, not just the browsers,/ to hold the wolf and the lamb in one fold/ for one long minute". For the shepherd of Canterbury, that's easier said than done.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments