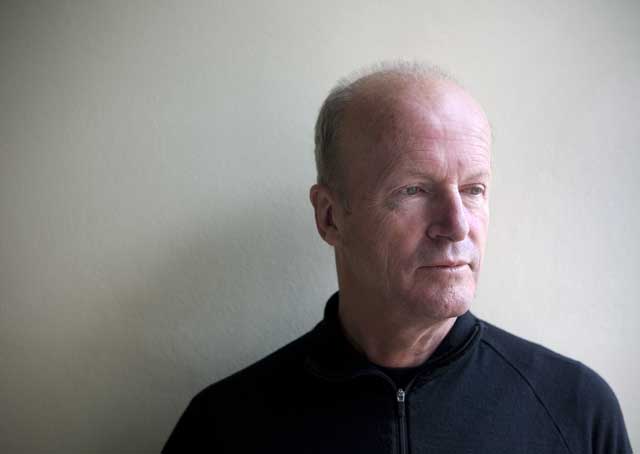

A radical proposal: Why will Jim Crace's next book be his last?

Jim Crace made his name with literary fiction, but his new novel lurches in an entirely new direction: real-world politics.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jim Crace is describing how, last autumn, he found himself living next door to Laura Bush. "There was only this much space" – he stretches his arms out wide – "between us." Crace was renting a house in Austin, Texas, while spending a semester teaching at the city's university. The wife of the former president came regularly to stay next door with her best friend – "otherwise a progressive woman" – who also happened to be Crace's landlady.

So, did he meet the book-loving, one-time librarian and ex-First Lady? "Noooh." His arms drop to his sides and he makes it sound like a relief. It wasn't, he explains, because of any violent antipathy to her husband's politics. "I was terrified because I knew that meeting her would have made a perfect circle. In the book I had just finished, I had given Laura a bloody nose. Literally. And all the time she was next door – that sat uneasily on my conscience."

The novel in question, All That Follows, is out this week and features Mrs Bush in a cameo as the victim of a violent assault. Though largely set in the curiously featureless landscape of Britain in 2024, it also has substantial flashbacks to Texas in 2006, and an idealistic but bungled attempt to stage a headline-grabbing protest against George W Bush by disrupting his wife's speech to a children's literary festival. Laura Bush – who, despite never quite meeting her over the garden fence in Austin, Crace admits he is disposed to believe isn't quite as supine as she has been painted ("she dated a Democrat and married Bush on the rebound") – ends up on the floor with blood pouring out of her nose.

All That Follows is an unashamedly political book and, in that sense, marks something of a departure for Crace. "I wanted a change with this novel," he confirms. "I wanted to lose myself for a bit and I felt I could afford to be reckless. I wanted to see whether I could pull off a book where I do the things which I don't normally do well. I'm recognised – and I'm sorry if this sounds vain – for long metaphors and rhythmic prose that is poetic and very structured in nature, moralistic and not ironic in tone. And I'm comfortable with that. But I'm not good at dialogue. I'm not good at holding a mirror up at a real world. I'm not good at believable characterisation. And so I thought, 'I want to have a stab at that.'"

While successful writers will happily talk about wanting to try new things rather than repeat the same old formula, it is rare to find anyone making a short-list of their failings quite so bluntly as Crace does. Even rarer when they have a shelf-load of awards: Whitbread First Novel of the Year in 1986 for Continent, Whitbread Novel of the Year for Quarantine in 1997 (also Booker short-listed) and the National Book Critics Circle Award in 2000 for Being Dead.

But there is something endearingly down-to-earth about the 64-year-old Crace. He has never been one to generate headlines by sounding off in public or on literary stages. Indeed, his profile is so low here that a Scottish paper recently referred to him as "the cult American writer". We are talking in the kitchen of his modest semi in the Birmingham suburb of Moseley. He still works in a cluttered converted garage, even though his two children have grown up and flown the nest (his daughter, Lauren, is an actress in EastEnders). And this slight, gently spoken man is clearly more comfortable discussing his adopted city's unfashionable reputation or his former career as a "middling" journalist than he is the string of novels that have brought him acclaim around the world.

These have tackled big, eternal themes such as life and death, God and Darwin. All That Follows, by contrast, has in its political subject matter a much narrower focus. "When I was a youngster," Crace recalls, "I was brought up in a very political background on an estate in north London. Part of me has been aware for a long time that my radical 17-year-old self would have despised the bourgeois literature that I have ended up writing. So part of the mix for this book was to write something with an agenda that my 17-year-old self would like."

The central character is Lennie Lessing, a jazz musician (Crace is a jazz fan) who is nearing his 50th birthday with the best days of his career apparently behind him and a paralysing addiction to screens. As he is switching between news and information channels that are covering the death of the final Rolling Stone, he latches on to an unfolding hostage crisis and recognises the Photofit of the lead kidnapper as Maxie Lermon. This was the man who, 18 years earlier, had been the moving force behind the "AmBush", the 2006 attack on Mrs Bush. Lessing had been part of it, but was tagging along more out of lust for Lermon's girlfriend, Nadia, than because of any radical conviction. When it came to the crunch, he bottled out, and has remained a coward ever after, albeit one with a buried grudge against Lermon for placing his spinelessness in such sharp focus.

"Lessing stands for the weakness in English bourgeois liberalism," Crace says, "the thing that I hate in my guts, the person who would rather not give offence than do the right thing. English politics is so much more concerned with the proprieties than with defending dogmas." With publication coming within two months of a General Election, All That Follows has a more immediate resonance than any of Crace's previous much-garlanded works. So where does he sit in this political clash between Lermon's direct-action conviction politics and Lessing's vacillating cowardice dressed up as polite good sense? Lessing, I suggest, is one of the most perfectly drawn but fundamentally unappealing characters I have come across in a long time. "Well, neither of them is likeable," Crace replies. "With Lermon, I have been around left-wing politics for long enough to recognise that there is a psychopathy there. And I recognise that psychopathy to some extent in me, running in parallel with my timidity."

The two men, then, both reflect aspects of his own character. "When I was younger," he remembers, "I wanted to be brave politically, but I wasn't. I remember being on a demonstration at Brize Norton air base, and the whistle went to sit down in the road and be arrested, but somehow I managed to sit with my bum on the pavement and my feet in the gutter rather than in the middle of the road. And by the time the police had arrested everyone in the middle of the road and reached me, I had my feet up on the pavement too. As far as I knew, it wasn't an offence to be on the pavement." At least, he reflects with a warm laugh, he is now being politically courageous as a writer.

He is, he says, already at work on his next novel. Will it follow the direction of All That Follows, or return to more familiar territory? The latter, he confirms, and then adds – very casually – that it will be his last book. "Writing careers are short," he expands. "For every 100 writers, 99 never get published. Of those who do, only one in every hundred gets a career out of it, so I count myself as immensely privileged. I will have written 12 novels when I finish this next book and it's enough. I'm going to stop. Too often bitterness is the end product of a writing career. I keep seeing writers who have grown bitter. And I know that I am just as likely to turn bitter as anyone else. So it's self-preservation."

Most writers would say that they are driven to write and know no other way to fill their time or make sense of the world. Crace is amused by their presumption. "My belief is that I will be quite happy not writing. JD Salinger once said, 'You've got no idea the peace of writing and not publishing,' but I am going to go one better and find the peace of not writing and not publishing. I'm looking forward to it."

The extract

All That Follows, By Jim Crace Picador £16.99

'... Nadia has jumped up on the great oak Speaker's table before the first protector, a beefy, uniformed state trooper, has succeeded in grabbing her ankle and succeeded too in toppling Nadia off the table and on to Laura Bush. There is an audible clash of heads. Inexplicably Nadia has not attempted to roll off her victim, but is ... gripping her by the lapel of her pearl pants suit'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments