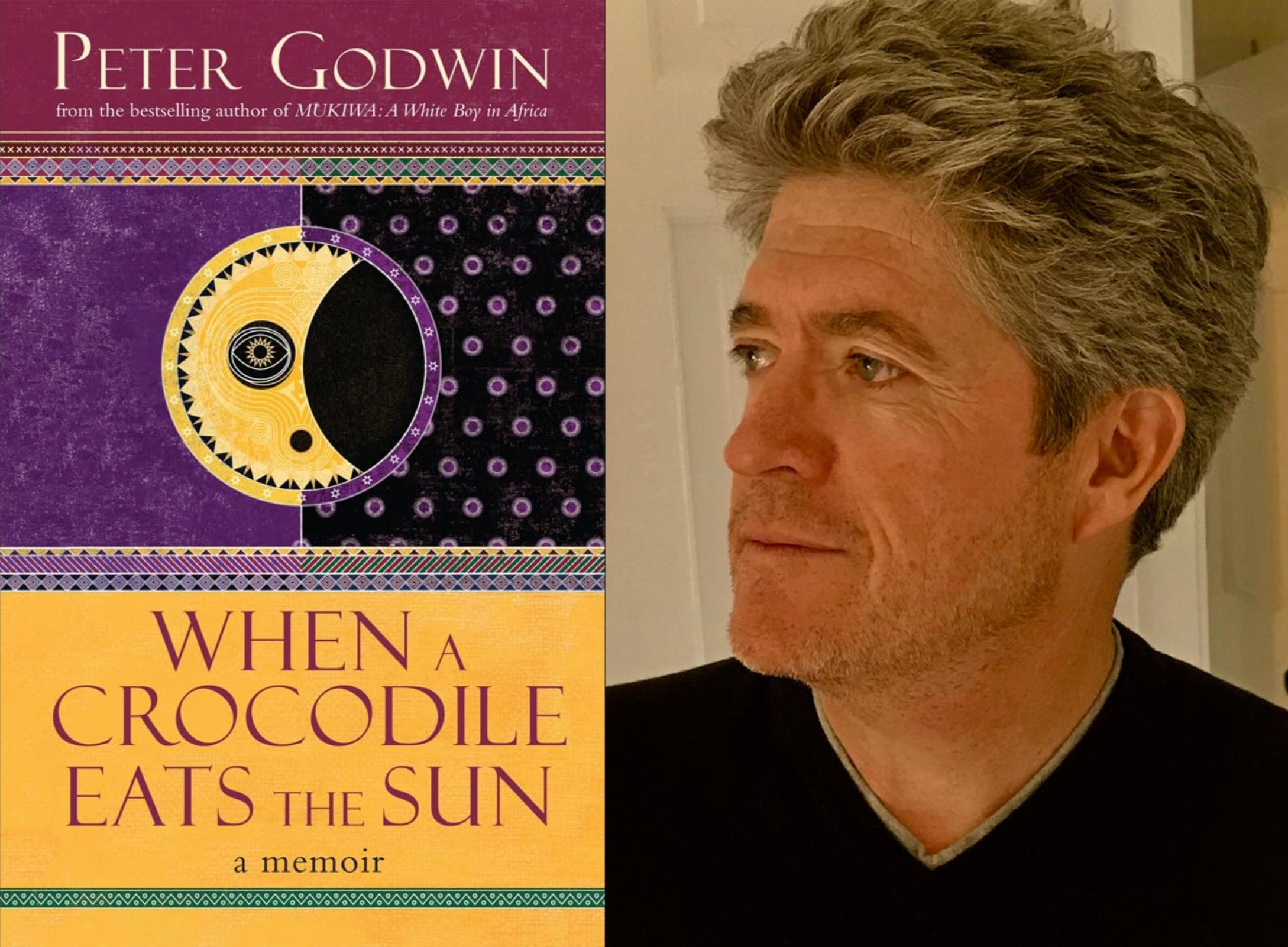

Book of a lifetime: When a Crocodile Eats the Sun by Peter Godwin

From The Independent archive: Nicola Barker devours literary caviar in a memoir about the disintegration of Zimbabwe that is a joyful celebration of the horribly cracked prism of life

Peter Godwin has written three pretty much universally acclaimed, semi-autobiographical books about Zimbabwe. While When a Crocodile Eats the Sun is one of my favourite books of all time, I have yet to read the other two because I loved this one so intensely.

It demanded so much, was so colourful, so wise, so... well, edifying, that I feel as though I have to do something amazingly heroic to earn the privilege of reading his others. It’s anal, I know. I apply the same cracked logic to the books of my other all-time favourite author, Thomas Mann. Godwin – like Mann – writes literary caviar.

If I had to place Godwin into a fold – a category – of writers, I would bracket him with Ryszard Kapuscinski and Jonathan Kaplan (the viscerally brilliant South African doctor/writer). Godwin really can stand shoulder to shoulder with the best of them.

His writing style is engaging, immediate and utterly involving. He is a natural storyteller. If there is a bird or a smell or a flowering tree then you will instantly be introduced to it, listen to the cadences of its song or gingerly inhale its curious scent.

But it’s not just Godwin’s fascinating and often menacingly inexplicable exterior world that keeps you glued to the page; it’s his wonderfully illuminated interior world. He is a master of self-examination and he is full of love. Every line of this marvellous and gripping work exudes it.

When a Crocodile Eats the Sun is principally a book about the disintegration of Zimbabwe in the 1980s and 1990s, filtered through the mechanism of Godwin’s relationship with his ageing parents.

It’s a tried-and-tested formula for books of this stamp, but Godwin’s parents are both exceptional individuals and deserve to have a book or three written about them. Nothing here is carefully meted out. This is a condensed kind of literary milk.

I might be expected to have a special, heightened, connection to this book because of my own childhood spent partially in apartheid South Africa, but I believe that its reach is universal. It is a story, at root, about the nature of belonging, a story about the “inside outsider”, about fairness and truth and honour and inequality, and as such it transcends all boundaries.

It is a joyful celebration of the horribly cracked prism of life. Reading it is like taking a harrowing holiday in a bright/dark world and returning to the comforts of home with a malady – a fluttering heart-sickness – which defies all traditional forms of medication, which simply cannot, and should not, be healed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments