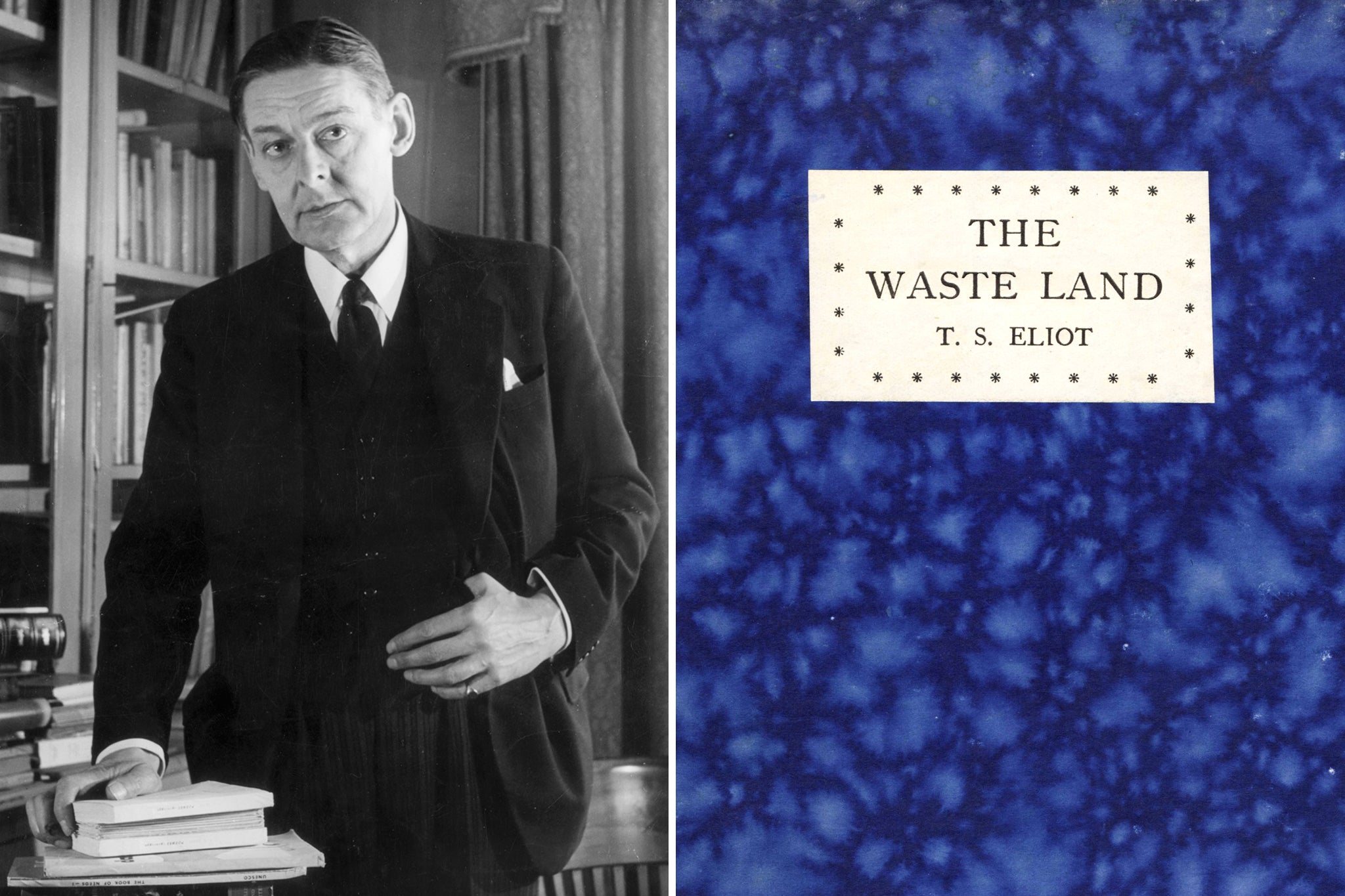

Book of a lifetime: The Waste Land by TS Eliot

From The Independent archive: Sally Gardner read ‘The Waste Land’ when researching the period between the two world wars for her new book and became utterly bewitched by its fragmented narrative

It is rare indeed to find someone who has stumbled unburdened by preconceived ideas upon this goliath of a poem. I used to believe that TS Eliot’s The Waste Land, buried deep under a monstrous papier mache pyramid of footnotes, dissertations, theories and essays, was well out of my reach.

“O O O O that Shakespeherian Rag –/ It’s so elegant/ So intelligent.”

I had been put off at an early age. I was told that I needed an English degree to properly understand it. So I didn’t read it. Then, two years ago I began work on my new book The Double Shadow. I knew that at the centre of my novel lay a memory machine. It was while pondering this notion of how memory defines us, collectively and individually, that I started research into the period in which the book would be set, between the two world wars.

I became fascinated by Ezra Pound and the part he played in the editing of The Waste Land. My interest in Pound’s literary and financial generosity towards Eliot’s work finally led me, rather reluctantly, to listen to a friend’s treasured recording of the reading by Ted Hughes. I sat, mesmerised, certain that there must be some terrible mistake. Surely this couldn’t possibly be that poem, the one wrapped around with so much intellectual barbed wire that it had managed to frighten off many a mere mortal? What I was listening to was a simply electrifying, helter-skelter ride, second to none. Cinema for the mind, sweets for the tongue, music for the ear. A diamond that no amount of academic “jug jug” should ever be allowed to dull.

I am never sure if you choose the book or the book chooses you. I do know that from the moment I heard The Waste Land, I was bewitched by the way Eliot (or Pound) had fragmented the narrative, distilled it like a fine wine into the essence of storytelling in all its many disguises.

I have spent many a happy hour contemplating Madame Sosostris, and her wicked pack of cards, but here Eliot is the famous clairvoyant. This poem was first published in 1922; cinema was still in its infancy, there was no TV, no internet, no mobile phones. He foresaw the future for a teller of tales. Today many of the stories we share come to us through collages of paper and multimedia technologies, staccato snippets, interrupted trains of thought, tales from the babbling tower, broken images on the cutting-room floor. There is never the time to listen to one voice. Too many stories are shouting to be heard. All this and more is captured in The Waste Land. Eliot gives us a library of unfinished possibilities.

Hurry up please it’s time.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments