Book of a lifetime: Microscripts by Robert Walser

From The Independent archive: Luke Williams celebrates the mysterious handwritten scraps – only deciphered decades after the author’s death – that revealed one of the most remarkable examples of Modernist literature

Wednesday afternoons in primary three were given over to free writing. I remember this only because of one particular class. While the rest of us struggled to compose our stories, a boy whose name I forget was scribbling at such a rate he broke his pencil. He was given a new one, and he continued with furious concentration, even after the teacher had ended the session. What had possessed this otherwise unremarkable boy? What was his story? He had not been writing a story at all, we later discovered, but the same word over and over again.

I don’t think I ever knew what that word was. What remains is the sight of him writing feverishly, the physical labour of it. There was something compulsively wretched in the way he covered page after page with this barely legible script. It was in the action, not the word, that meaning resided.

About the time of the First World War (the exact date is unclear), the Swiss writer Robert Walser developed his “pencil system”, a method of literary composition requiring him to write in radically shrunken letters. Walser had been a prodigious and acclaimed author of novels, stories and essays. Hesse and Kafka admired his work. But by the 1920s his output had stalled. Responding to a “hideous” and “frightful” hatred of his pen, he took up a pencil and “learned again, like a little boy, to write”.

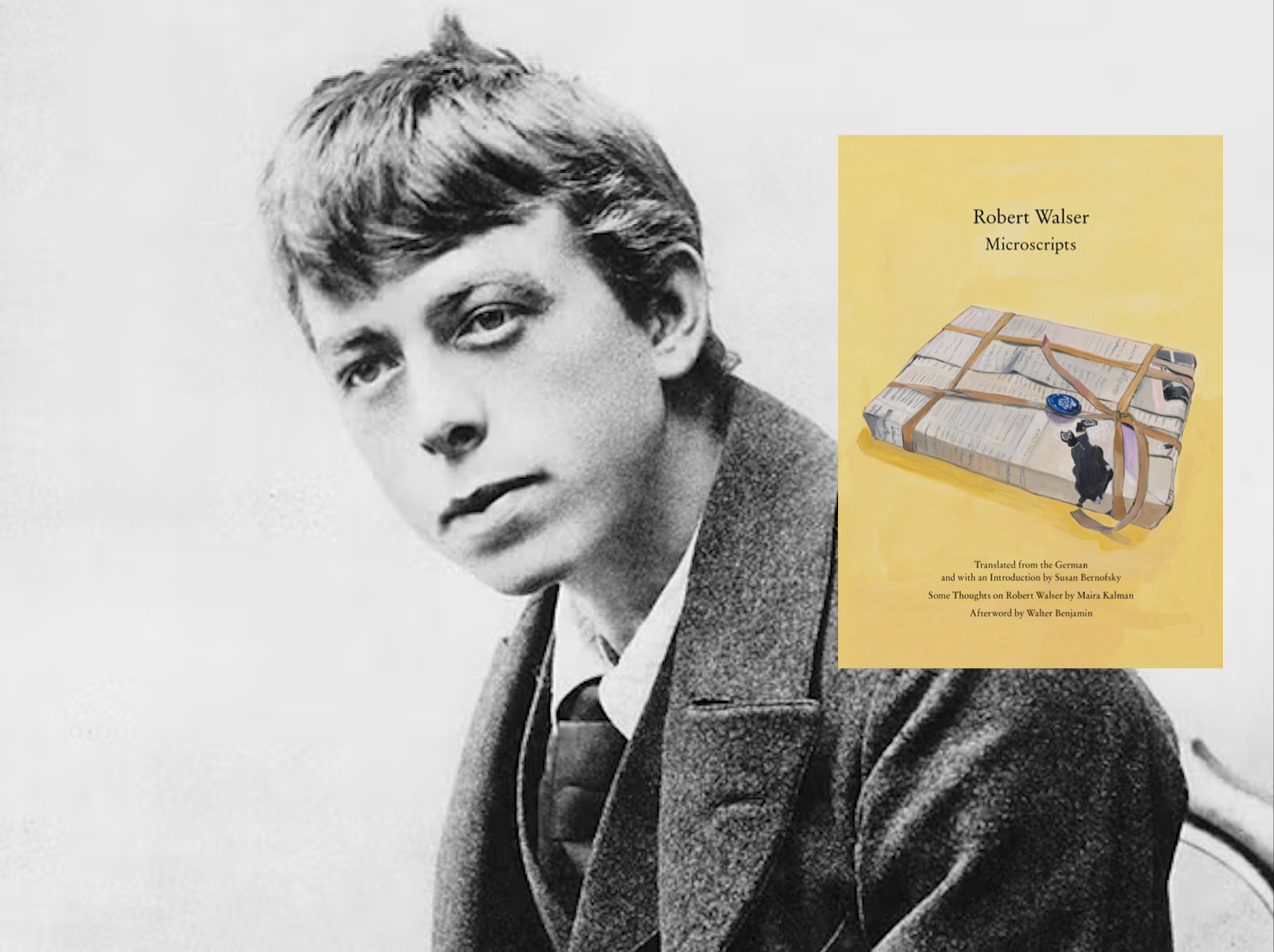

The result was one of the most remarkable, idiosyncratic, mischievous periods of Modernist literary output. He wrote in a Kurrent script so small and obscure that for years scholars considered it indecipherable, on tiny scraps of paper. Walser produced more than 500 such prose pieces before he stopped writing altogether sometime in the 1930s. Microscripts, brilliantly translated into English by Susan Bernofsky, comprises a selection of these.

It’s difficult to summarise their effect. Sketches, parodies and notes relate trifling incidents in unexceptional lives; the prose is chirpy, oblique, at times banal, always self-effacing. Plot and characterisation barely figure. It’s as if, having pioneered and mastered his pencil system, Walser had freed himself from the obligations to write stories. “These lines of mine are autumnally fading,” he writes in microscript 72, “with which, in point of fact, their purpose has been fulfilled.”

What thrilled me above all on reading Microscripts was the relationship between the stories and the handwritten scraps, reproduced in the book as photographs. The effect for me is bound up with the mystery of the boy in my class. Like Walser, he wrote in a private form – the barely-legible handwriting, the single word repeated – and like Walser, his interest lay in writing’s labour rather than its communicative potential.

The boy’s scrawl, and Walser’s work, has come to represent for me language’s failure to adequately represent experience, even as it rails against this. Language is all that connects us to ourselves and to others, and to celebrate this even while we mourn the fragility of our connection to the world is, in the end, to come down on the side of life.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments