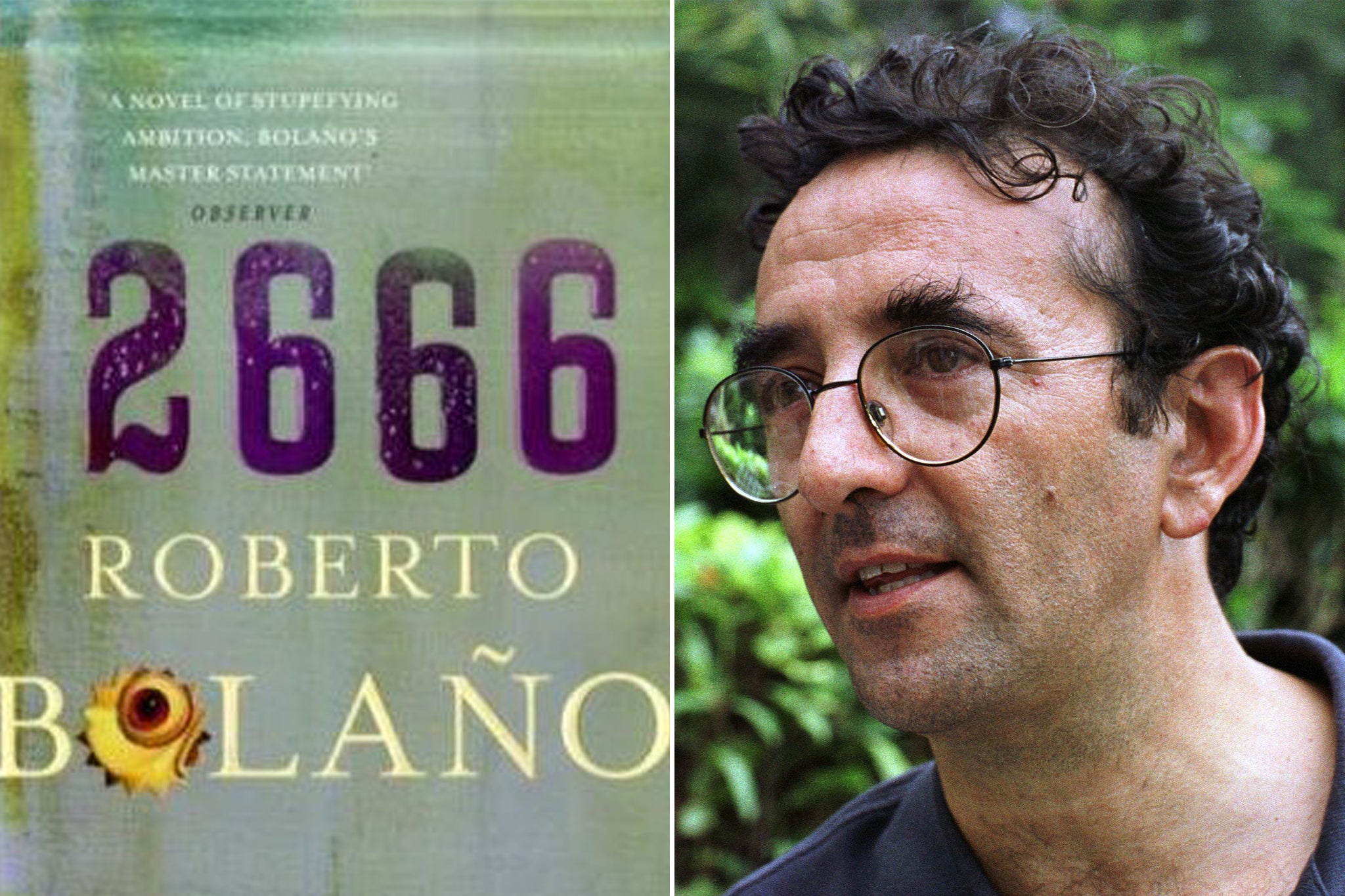

Book of a lifetime: 2666 by Roberto Bolaño

From The Independent archive: Jeet Thayil takes pleasure in the way profound aesthetic ideas occur at casual moments in a book Bolaño knew would be published after his death

First published in Spain in 2004, a year after the author’s death, 2666 appeared in English translation four years later. It is, among other things: a Russian war epic; an American reporter’s hard-boiled take on Mexico, boxing and love; a grisly if verifiable police procedural; a study of mental and other derangements; a skewed and scholarly view of the (great) writer’s life; a prison chronicle.

2666 is also a kind of time bomb. It hasn’t been around very long but it casts an impregnable shade of influence. It’s not unreasonable to speculate that in a decade or so it will be Bolaño, not Márquez, who will be considered the pre-eminent Latin American novelist of the 20th century.

Great books develop their own mythology. Bolaño wrote his when he knew he was dying. Though he is a master of the unsaid, of Dostoyevskyan digression and the open ending, the book’s last part doesn’t feel like its end. Which, apparently, it wasn’t: Part VI was found among his papers after his death. Knowing how self-aware the author was, he likely anticipated the kind of reception 2666 would receive and withheld the last part for sensational posthumous publication.

One of the pleasures of Bolaño is the way profound aesthetic ideas occur at casual moments. In Book II, Amalfitano, a professor of mathematics, holds conversations with a familiar voice that announces, among other things, that calm is the only thing in the world that will not let us down. Ethics will let us down, the voice says, as will the sense of duty, as will honesty, curiosity, love, bravery, art; everything lets us down. There is no love, no friendship, no lyric poetry “that isn’t the gurgle or chuckle of egoists, the murmur of cheats, the babble of traitors, the burble of social climbers, the warble of faggots.”

But, 15 pages later, Amalfitano runs into a young man who introduces him to a lost brand of mescal called Los Suicidos. The man cruises the city at night, he says, and gets into fights: sometimes he is beaten and sometimes he does the beating. Either way, he needs the release. Amalfitano asks the man what he reads. The reply is a theme that recurs across the vast range of Bolaño’s fiction and poetry: “I used to read everything, Professor, I read all the time. Now all I read is poetry. Poetry is the one thing that isn’t contaminated, the one thing that isn’t part of the game. I don’t know if you follow me, Professor. Only poetry-and let me be clear, only some of it is good for you, only poetry isn’t shit.”

The year 2666 is never mentioned in the novel. You have to go to another Bolaño story to understand the title, which is meant to represent a time so far in the future as to be almost unimaginable. This much we can imagine: if, at that time, books are still read, 2666 will be among them.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments