Book inscriptions reveal the forgotten stories of female war heroes

A simple signature can lead to an incredible story

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Open up a book from the late 19th or early 20th century, and chances are that you will find an inscription inside the front cover. Often, they are nothing more than handwritten names that state who owned the book, though some are a little more elaborate, with personalised designs used to denote hobbies and interests, tell jokes or even warn against theft of the book.

While seemingly insignificant markers of ownership, book inscriptions offer important material evidence of the various institutions, structures and tastes of Edwardian society, and act as tangible indicators of class and social mobility in early-20th century Britain. They can also reveal vast amounts of information on how both attitudes of ownership and readership varied according to geographical location, gender, age and occupation at this time.

My research involves collecting these inscriptions from secondhand books and working with archives to delve into the human stories behind these ownership marks. I am particularly interested in “everyday” Edwardians – the miner, the servant, the clerk – who are so often forgotten by time, yet played an essential role in ensuring Britain ran smoothly during the war years.

My latest work has focused on the stories of the female heroes of World War I. They weren’t fighting on the battlefield, but their contributions at home and abroad were nothing short of incredible. Using the inscription marks they left in books, censuses, local history, and Imperial War Museum archives, I have tracked several untold tales, two of which I’ve written about here.

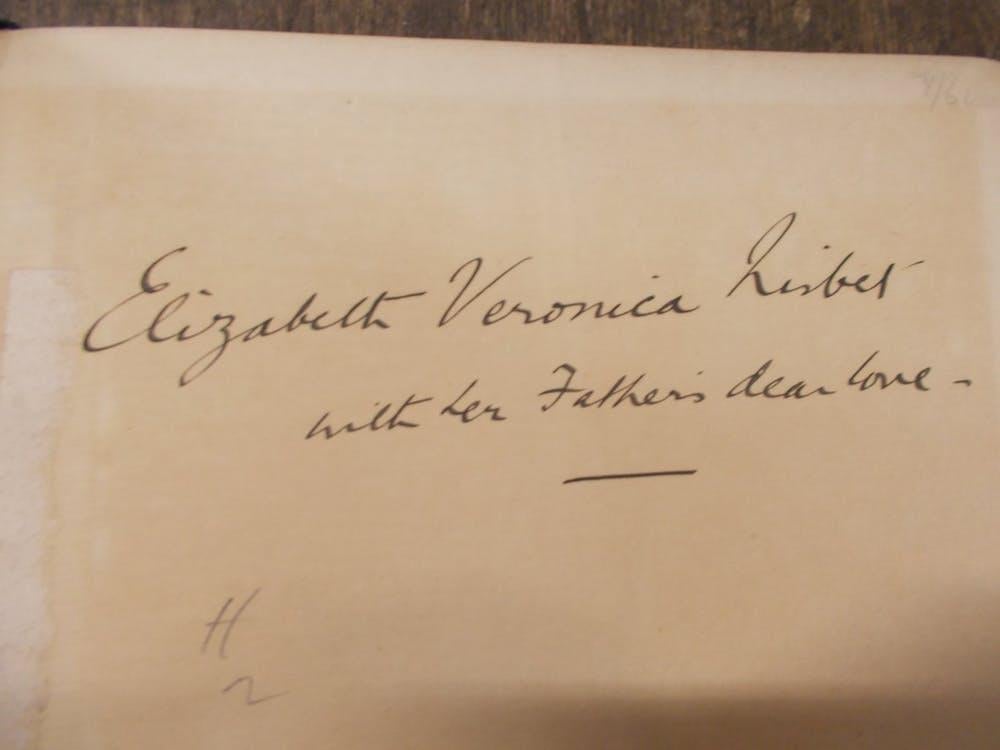

Elizabeth Veronica Nisbet

Elizabeth Veronica Nisbet was born in 1886 in Newcastle. The daughter of a colliery secretary, Nisbet was part of the lower-middle class that emerged in Britain at the end of the Victorian era. She studied art at Gateshead College before serving as a nurse with St John Ambulance and the Royal Victoria Infirmary.

In 1913, Nisbet’s father gave her a copy of the biography of cartoonist George Du Maurier, and inscribed it “with dear love”. Du Maurier was well-known for his cartoons in the satirical magazine Punch, which inspired Nisbet’s own artwork.

Just one year after receiving the book, World War I broke out and Nisbet headed to France to aid wounded soldiers at St John Ambulance Brigade Hospital in Étaples. This hospital was the largest to serve the British Expeditionary Force in France and treated over 35,000 casualties.

Throughout these troubled times, Nisbet’s passion for art was her salvation: she kept a scrapbook of cartoons, sketches and photos, which provide an insight into wartime Étaples and the vital work of the female nurses. Looking at her artwork, it is clear that she was strongly influenced by the cartoon style of Du Maurier, suggesting that the book remained a treasured artefact to her while she was serving in France.

Today Nisbet’s work is kept at the Museum of the Order of St John in London. After the war, she returned to Newcastle and worked again as a nurse until the 1920s when she became a full-time artist, travelling regularly to the US and Canada to showcase her work. She died in 1979 at the age of 93.

Gabrielle de Montgeon

Born in France in 1876, Gabrielle de Montgeon moved to England in 1901 and lived in Eastington Hall in Upton-on-Severn throughout her adult life. She was the daughter of a count of Normandy and part of the upper class of Edwardian society.

Her affluence is showcased in the privately-commissioned bookplate found inside her copy of the 1901 Print Collector’s Handbook. The use of floral wreaths and decorative banderoles in her plate – both features of the fashionable art nouveau style of the period – mimic the style of many of the prints in her book. This demonstrates the close relationship that Edwardians had between reading and inscribing.

Stepping out of her upper class life, during World War I, De Montgeon served in the all-female Hackett-Lowther Ambulance Unit as an assistant director to Toupie Lowther: the famous British tennis player who had established the unit. The unit consisted of 20 cars and 25-30 women drivers, who operated close to the front lines of battles in Compiegne, France. De Montgeon donated ambulances and was responsible for the deployment of drivers.

After the war, she returned to Eastington Hall and led a quiet life, taking up farming, before passing away in 1944, aged 68.

Considering the testing circumstances of war, the survival of these two books (and their inscriptions) is a remarkable feat. While buildings no longer stand, communities have passed on, and grass on the bloody battlefields grows once more, these books keep the memories of Nisbet and De Montgeon alive. They stand as a testimony of the unsettling victory of material objects over the temporality of the people that once owned them, and the places in which they formerly dwelled.

Lauren O’Hagan is a PhD candidate in language and communication at Cardiff University. This article was originally published on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments