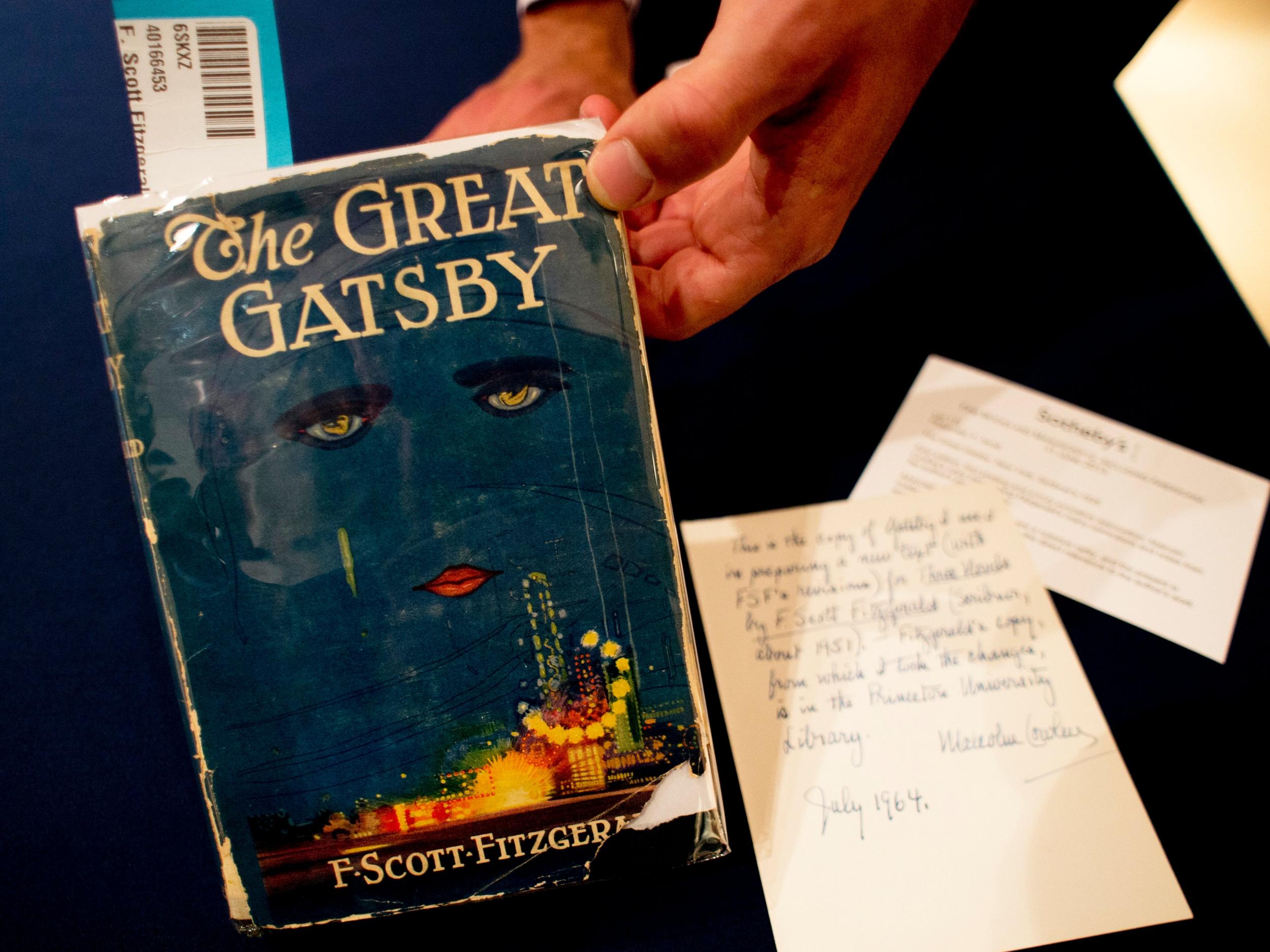

Book of a lifetime: The Great Gatsby by F Scott Fitzgerald

From The Independent archive: a love story, an American fable and an echo chamber of the 20th century. Whenever Alan Glynn revisits this extraordinary study of the power of illusion, dreams are deconstructed

The Great Gatsby by F Scott Fitzgerald is one of those rare books that shouldn’t ever be adapted for the screen. Seriously. But it keeps happening. In 2013, Baz Luhrmann made a version of it in 3D with Leonardo DiCaprio and Carey Mulligan. It took me 35 years to shake Robert Redford and Mia Farrow out of my head, and then I had to contend with those two. It’s not fair.

And it’s Daisy, more than Gatsby, that’s the problem. To cast her, to objectify her, is straightaway to diminish her impact as a character. I felt the same way about Anjelica Huston’s Gretta Conroy in The Dead. Because however many dimensions you manage to pack up there on the screen, you’ll only really be getting one. On the page, by contrast, in astonishingly beautiful, layered prose, what Scott Fitzgerald manages to do is to replicate some of the mystery of what it is to be human, and that can only properly be experienced inside your head.

Published in 1925, The Great Gatsby, a “consciously artistic achievement”, is a study of the power of illusion. It’s a deconstruction of our dreams – of romance, of identity, even of consciousness. It’s a love story, an American fable and an echo chamber of the 20th century. For these reasons it is also one of those rare books that you can read at different times in your life, and each time it’ll do something different to you.

When you’re young, Gatsby’s desperate pursuit of Daisy might break your heart. When you’re older, the fragility of Gatsby’s reinvented self might crack your soul. Whenever you do read it, though, you’ll never be in any doubt that you’re reading something extraordinary.

If the book is tugging at your heart, you’ll find the language lush and iridescent, and the imagery sensuous, with its calibrated system of blues and yellows, of eyes and water, of honey and straw. If it’s chipping at your soul, you’ll find the language weighted and resonant, and the imagery quite simply unforgettable, with its poetic elevation of the quotidian to the level of the profoundly philosophical.

In fact, with the elaborate but unstrained imagery of the “valley of the ashes” and the eyes of Dr TJ Eckleburg, Fitzgerald pretty much did what Joyce did in Ulysses and Eliot in The Waste Land. By pitching an all-seeing God against an all-pervading advertising billboard, he looks back in sadness to an imagined lost world, but also looks forward in anxiety to a burgeoning new one.

But let’s not forget Jay Gatsby. Whenever I revisit the book, I imagine that this time, somehow, it will all work out for him. The Great Gatsby retains that tension, that pull on the reader, taking us back, every time, to the blue lawn, and the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks