Zaha Hadid: How did she change architecture and its view of women?

The larger-than-life artist, who was widely regarded as the greatest female architect of her time, reshaped architecture for the modern epoch and smashed the glass ceiling to smithereens

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Initially dubbed the “paper architect”, Dame Zaha Hadid’s plans were once perceived to be unbuildable. For years, her designs struggled to move beyond the sketch phrase and be transformed into bricks and mortar.

Nevertheless, this did not last long. Thanks to her unshakeable determination and fierce dynamism, the Iraqi-born British architect became known for building the unbuildable.

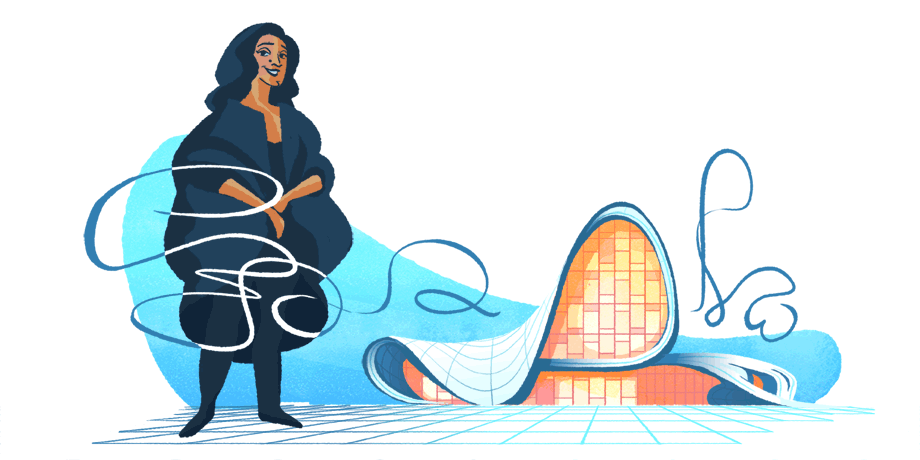

Today, Hadid’s ongoing legacy, embodied in her creations around the world, is being honoured with a Google Doodle – in honour of the day, in 2004, when she became the first woman to win the coveted Pritzker Architecture Prize.

Hadid, who is widely seen as the greatest female architect of contemporary times, reshaped architecture for the modern epoch. The esteemed but divisive artist, who died of a heart attack at the age of 65 last spring, was known for designs such as the London Olympic Aquatic Centre and the Guangzhou Opera House.

Her plentiful buildings appear all over the world, including in America, China and Switzerland; some of her most renowned commissions include the London Olympics, Glasgow’s Riverside Museum, the Cardiff Bay Opera House and the 2022 Fifa World Cup Stadium in Qatar.

Dubbed a diva, the caffeine-loving, chain-smoking “Queen of the Curve”, who won the Stirling Prize twice, was also famed for her larger-than-life personality.

Speaking about her tremendous acclaim in receiving the Royal Gold Medal for Architecture back in 2016, the artist, architect and designer said she still did not feel like she belonged to the establishment.

Nevertheless, she did admit: “I suppose I must be part of the establishment now. I’ve always been independent and, because I’m ‘flamboyant’, I’ve always been seen as difficult. As a woman in architecture, you’re always an outsider. It’s OK, I like being on the edge.”

This brings us to the question of how Hadid revolutionised modern architecture itself and the role of women within it.

She was renowned for her disregard for dull functionality and penchant for experimentation. The architect would not compromise her concepts or designs for practical constraints or technology. Instead, her swooping, curved, futuristic buildings tended to be structurally intricate.

But she did not just do away with boundaries; her flamboyant buildings arguably helped to popularise and thus glamorise architecture into something for onlookers to enjoy rather than merely utilise.

Hadid also massively changed the industry for fellow female architects. She gave them a role model and someone to inspire towards, as Despina Stratigakos, associate professor and interim chair of architecture at the State University of New York and author of Where Are The Women Architects?, explains so lucidly in a piece for The Conversation in the wake of Zaha’s death.

“With Hadid’s passing, we have lost a role model in a field that has few others,” she says. “That is not to say that there are not a great many accomplished and inspiring women in architecture. But none have achieved Hadid’s prominence – as, indeed, have few male architects.”

“Against all odds and a great deal of prejudice, she broke one glass ceiling after another, no mean feat when that glass was as hard and thick as concrete.”

In recent years, she had become increasingly vocal about the professional challenges she was forced to deal with as a woman.

Interestingly, in 2013 she told Business Insider she had faced “more misogynist behaviour” in London than anywhere else in Europe and that the state of play was not improving for women in architecture.

“I am non-European, I don’t do conventional work and I am a woman,” she once told an interviewer. “On the one hand all of these things together make it easier – but on the other hand it is very difficult.”

But Hadid was not just a woman in an industry dominated by men, she was also a person of colour in a predominantly white field.

It’s worth noting that as celebrated as Hadid was, she was not free of controversies. She received great criticism from human rights campaigners when her $250m (£194m) cultural centre in Baku, Azerbaijan, forced families to be evicted from the site, as well as for a number of her other projects.

Nevertheless, however you feel about Hadid, it cannot ever be denied that she was a force to be reckoned with and a tremendous pioneer in the architectural world. In the words of her mentor Rem Koolhaas, she was “a planet in her own inimitable orbit”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments