Threads of Feeling, The Foundling Museum, London

Mothers and babies whose lives hung by a thread

Desperation is a terrible thing to find seeping from the pages of a register.

Bureaucratic documents more than two-and-a-half centuries old cannot wring their hands or weep. And no doubt the functionaries who painstakingly registered each abandoned baby at Thomas Coram's found-ling hospital between the years 1740 and 1770, noting its age (rarely more than four weeks), gender and clothing (sometimes "verminous rags"), were soon enough hardened to the task.

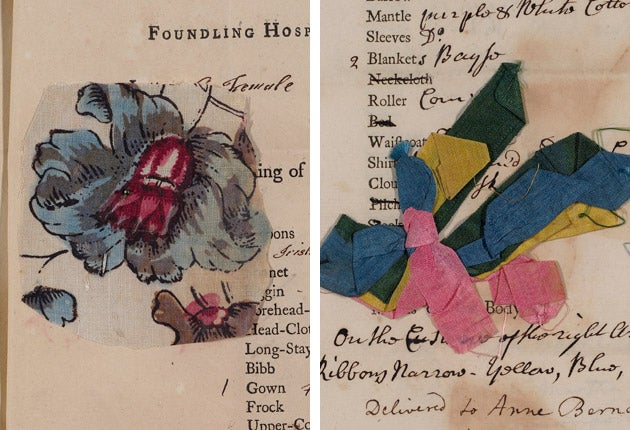

The desperate party was the baby's mother. Her anonymity assured by the hospital, she was urged to leave with the baby an identifying token, partly with a view to her retrieving the child should her circumstances ever improve. Sometimes this took the form of a coin, cheap watch seal or string of buttons. More often though, mothers left a swatch of fabric, probably cut from their own clothing, which was then pinned to their registration paper with a detailed description. Threads of Feeling, an exhibition at the handsome former hospital premises in Bloomsbury, has for the first time put on show some of these textile scraps – now of great value to historians, given that no examples of poor people's clothing of the period survive.

Camblet, fustian, susy, calimanco and linsey-woolsey – even to a non-historian, the sheer range of textile types and their names is intriguing. Few of the fabrics are what you'd expect from impoverished dressing, which is to say brownish and coarse. The lively flowered prints on linen or cotton strove to resemble the fashionable pale embroidered silks of the rich. On this evidence, even the lowliest 18th-century woman, however degraded, held tight to a degree of social aspiration.

More touching still are the forlorn hopes for the infant's survival. One mother had neatly snipped out a printed acorn, another a bird; many chose hearts. In the face of such testaments of tenderness, words are redundant.

To 6 Mar 2011 (020-7841 3600)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks