The EY exhibition: Wifredo Lam, Tate Modern, London: 'Not a waste of time nor mental space'

The subject of the latest monographic exhibition at Tate Modern is billed as the most important Cuban painter of the early 20th Century

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Wifredo Lam, the subject of the latest monographic exhibition at Tate Modern, is billed as the most important Cuban painter of the early 20th Century.

Lam’s history was one of nomadic movement propelled by events of the early 20th century. His father was a Chinese emigrant who settled in Cuba; his mother was Congolese African and Spanish; his godmother a Yoruba princess.

Lam was celebrated on both sides of the Atlantic, his work being in many prestigious museum collections. Born in 1902, Lam spent his formative artistic years studying in Spain before the death of his wife and child from tuberculosis became the catalyst to join up to the Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War. Forced eventually to flee Spain in 1938 he landed in Paris where he met Pablo Picasso and André Breton. Lam returned to Cuba in 1941 but left again in 1952 to spend his last few decades between Paris and Albissola in Italy. His ancestry continued to be an issue: he was denied citizenship from the US because his father was Chinese. He died in 1982, a refugee from his own country.

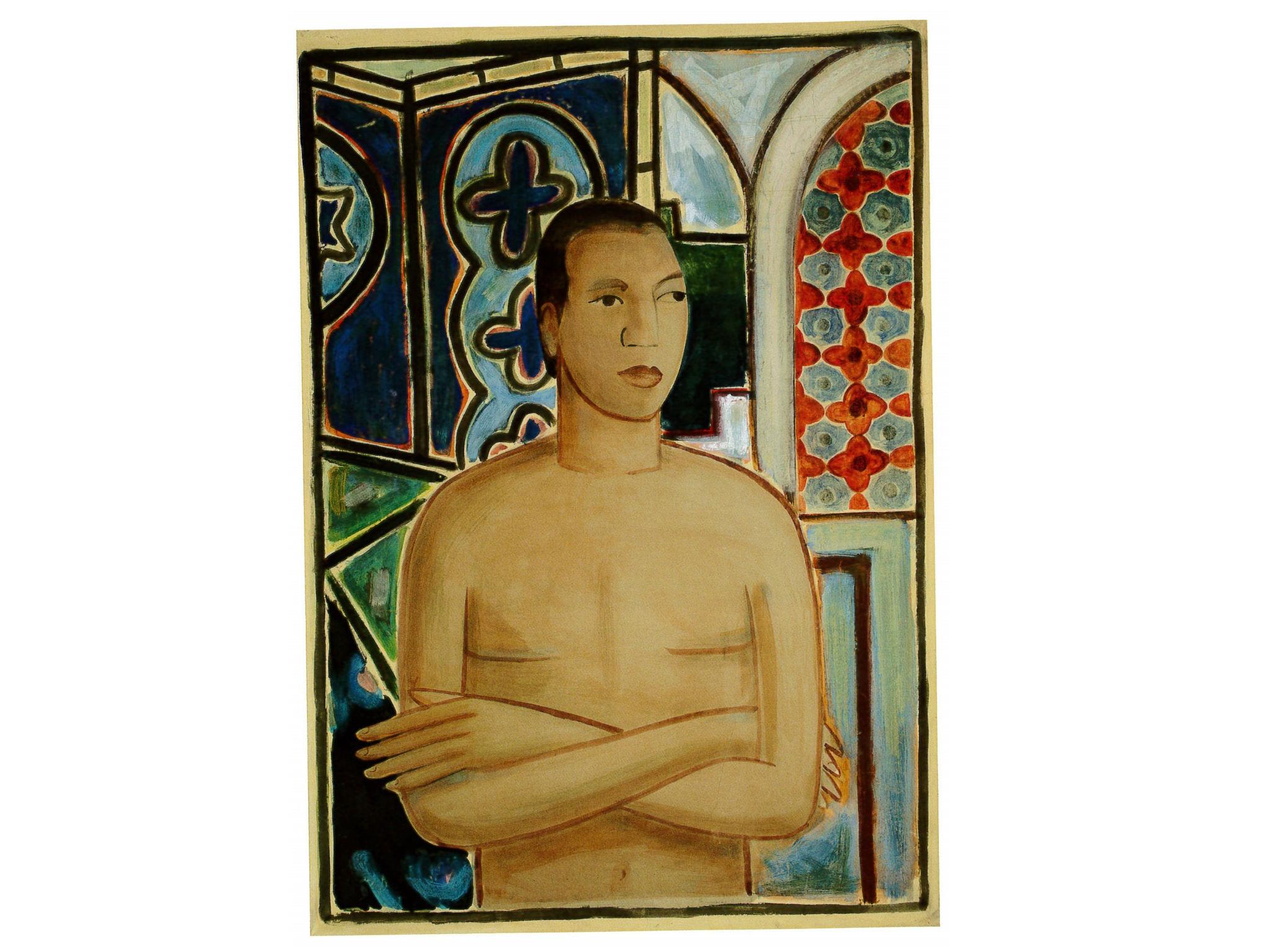

Two early self-portraits reveal much of Lam’s influences and heritage. Self Portrait II (1938) is heavily influenced by Matisse with its sumptuous palette and decorative back-drop, whilst Self Portrait III (1938) obscures the artist behind an African mask.

Lam spent much of the 1940s in Cuba and the paintings from this period are perhaps the strongest works. In his native land he produces works in a vocabulary most distinctly his own. There is still the shadow of Picasso, with the strangely disembodied bodies and quasi-caricature line. But there is a singular imagery, a mixture of voodoo and Surrealism amidst a vegetal setting that elevates them.

Retrospective exhibitions can be a strain. I recall an argument with the late great critic David Sylvester on what would be the optimum number of exhibits and we agreed on perhaps a rather arbitrary 65. But this exhibition with its mixture of paintings, drawings, prints, ceramics and documentary photography weighs in at more than 200 objects.

Is it worth persevering or is Lam yet another artist who has the technical ability to cannibalise the best of international artists without adding much himself to the personal discourse? There is originality in works such as Anamu (1942), where Lam daringly allowed seemingly unfinished blank canvas to set off the luminous central objects. Passages of rapid brush strokes and surreal detached lips and a fruity dangling breast convinces me that this visit is not a waste of time nor mental space. It seems a shame that this exhibition will travel only in Europe. Perhaps it is time to remind the Americans that there is knowledge to be had beyond the fences they are trying to build.

Until 8 January 2017, Tate.org.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments