Tacita Dean: Portrait, National Portrait Gallery, London, review: It's a bit like going to the cinema many times over for relatively brief periods of time

In the gallery’s first exhibition that is devoted entirely to film, Dean’s portraits of artists, writers, a historian and a dancer, are part of a collaboration with the Royal Academy and the National Gallery

Tacita Dean, unlike some of the other members of the Brit Art gang who emerged in the 1990s, is the most unsplashy and least street-recognisable of individuals, the most muted of those tiresome, roaring beasts. She probably prefers it that way. What counts in the end, after all, is the durability of the work, not how much posturing and look-at-me prattling you may have done in its presence in order to draw attention to it – and you. Essentially she is a filmmaker, though she does other things too – photography, drawing, postcard making, for example.

This spring no fewer than three major institutions in London are singing her praises. Portrait, a retrospective of her films, takes place at the National Portrait Gallery. A second exhibition, called Still Life, is at the National Gallery. The Royal Academy’s exhibition, Landscape, which opens in May, will explore Dean’s interest in landscape phenomena. That an exhibition of the moving image should be at the National Portrait Gallery at all is significant enough. The NPG has never devoted a show to a filmmaker until now. Its collections consist entirely of still images of the painted, photographic or sculptural variety.

The nature of Tacita Dean’s unstillness is rather particular to her. She doesn’t believe in digital. It is the world of analogue filmmaking, with its reels of films turning and turning on rackety spools mounted on to hefty, garrulous projectors, that she loves, and which she has consistently championed, and perhaps even helped to bring back from the brink of near extinction by being so vocal about it. These film portraits at the NPG are of artists, writers, a historian and a dancer, and each one is assigned its own darkened and self-sufficient breathing space, together with a modest curve of chairs. It’s a bit like going to the cinema many times over for relatively brief periods of time. Included here, amongst others, are films about David Hockney, Cy Twombly, Mario Merz, Merce Cunningham and the poet and translator Michael Hamburger.

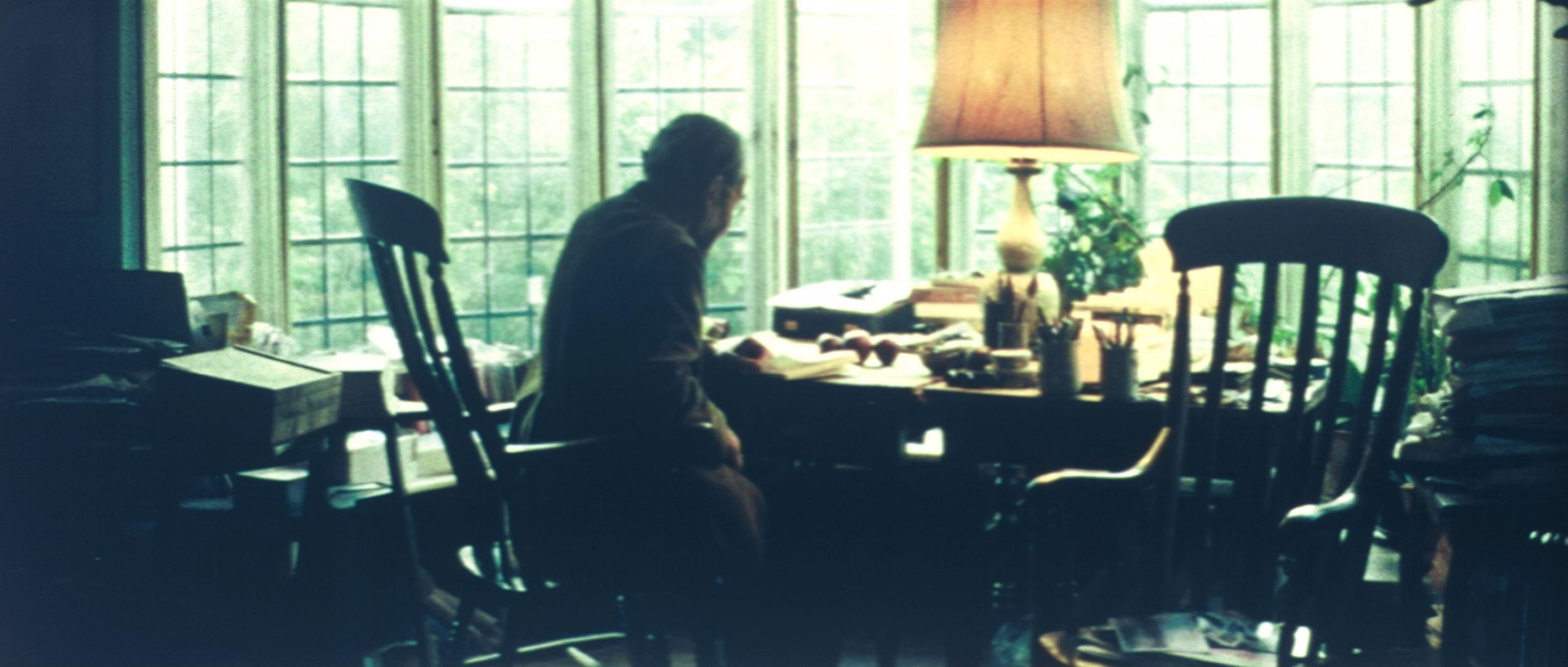

The analogue experience is an unsmooth one. It is grainy, flickery, jerky. It is not perfect. It does not elegantly self-preen. This lack of perfection is a good thing because we, the onlookers, are not perfect either. Nor are we glamorous – as, regrettably, the world seems so often to wish us to be. Dean does things in a hole-in-corner or through-a-keyhole sort of way – the blurrily odd detail, the too close close-up, the words that cannot quite be heard, the shadows that over-engulf the sitter. She spends such a long time close observing quite how much Hockney enjoys his favourite pastime of smoking, the way that those increasingly bony fingers seem to wrap themselves around the tip of the cigarette in a most deliciously long caress.

The film about Hamburger – her masterpiece – shows us very little of Hamburger at all. It is about his garden, and his wonderful apple orchard, and how it seems to embody him in all its wind-chafed restlessness. He is barely on the screen. The light rises and fades alarmingly, as if subject to fits of visionary intensity. When we do eventually spot him there, proceeding, hands knitted behind his back, at a ruminatively scholarly walking pace between his ancestral trees, and from time to time examining some rare wizened marvel of an apple, he is no sooner there than he is gone again. Yet he is present with such vividness in his absence precisely because she lingers over everything that always meant so much to him. His garden becomes a tempestuously romantic evocation of his nature. In short, she comes at the world so beautifully slant-wise, always. Face-on would be a crass betrayal of her subtle vision.

It is refreshing to be robbed of the artificial smoothness of the digital. The world is a messy, jagged, unpleasant place at the best of times.

Until 28 May (npg.org.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks