Shah 'Abbas: The Remaking of Iran, British Museum, London

A matchless exhibition unveils a ruthless Persian tyrant and his opulent taste

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Among the scores of exquisite things in Shah 'Abbas: the Remaking of Iran, one manuscript illustration seems to tell a big story on one A4-size sheet. In the very early 1600s, around the time that Shakespeare in Twelfth Night nodded to the riches of the Safavid ruler with his mention of "a pension of thousands to be paid from the Sophy", the court artist Habib Allah added new illustrations to a late 15th-century copy of the famous mystical poem, Attar's "Conference of the Birds". One of these paintings depicts, in sumptuous traditional style, the hoopoes, peacocks, herons, ducks and hawks as they gather by a river. But who's this skulking in one corner of the scene? A moustachioed hunter, armed with a musket of a very modern kind. Habib Allah makes the elongated barrel of this sinister weapon break through the edge of the painting into the blue borders of the page. New arms, and new arts, crash through the boundaries of a gorgeous, golden world.

The intimate kinship of firepower and fantasy has informed all of Neil MacGregor's blockbuster exhibitions on the art of globe-shaking rulers at the British Museum. After The First Emperor: China's Terracotta Army and Hadrian: Empire and Conflict, Shah 'Abbas paints at full length a cultivated despot who matched or topped them both in his fusion of taste and tyranny. Supported by the Iran Heritage Foundation, it's superbly curated by Sheila Canby, who also wrote the suitably splendid and covetable catalogue (British Museum Press, £25).

With Anglo-Iranian relations even dicier than usual, no visitor will miss the meta-show of quiet diplomacy that made all this happen. A British connection even bookends the whole experience. We begin with a portrait of the adventurer-turned-ambassador Robert Sherley. The Shah's envoy to the West when Europe craved Persian silks and other luxuries, he stands proud in his local bigwig's finery. His wife, the feisty Circassian Teresia, wields a scary firearm of her own.

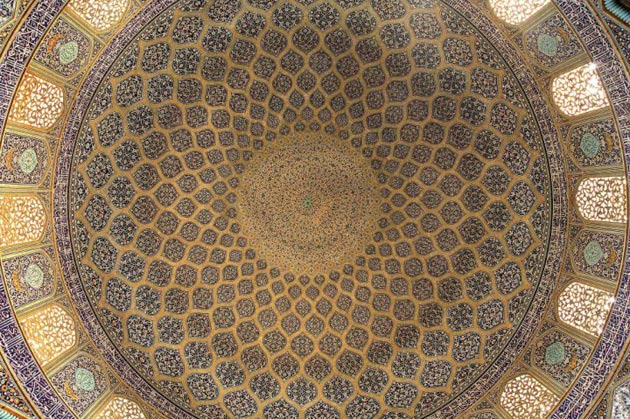

Shah 'Abbas: the Remaking of Iran is a triumph of curating and display, an experience as much as an exhibition. As the dark entrance passageway opens to reveal Panizzi's dome in the old Reading Room, lit to resemble one of the Shah's great mosques, a dramatic sense of theatre frames a show crammed with small beauties and big ideas.

Partitioned according to theme by latticed wooden screens and clay-coloured dividers, the layout takes us on a journey from Isfahan, the new capital where the Shah created his chief monuments, to the shrines of Ardabil, Mashhad and Qum. In these places, lavish donations shored up a policy of national unity – against the hostile Ottomans and Uzbeks on Iran's borders – and distinct religious identity, in a Shia state under threat from Sunni Muslim orthodoxy.

Shah 'Abbas, who reigned from 1587 to 1629, twinned public ostentation with personal discretion. Hardly any contemporary portrayals of him survive. A quizzical 1618 miniature by Bishn Das from Mughal India – Iran's closest economic and cultural partner – is the nearest we come to a court portrait. However flamboyant the twirly 'tache, the face of this ruthless nation-builder – who blinded two sons and killed another – gives little away. Later, an album illustration by Muhammad Qasim (from 1627) depicts the shaven-headed, middle-aged monarch canoodling with a pretty page-boy, who at lap level holds the stem of a wine flask at a saucy angle. The king commissioned it himself in an age when the royal mix of public piety and private indulgence raised no eyebrows.

Androgynous, dandified youths; bowers of sweet roses and serpentine vines; intricate floral decorations; luscious silks and velvets: the courtly polish of this show seems remarkably close to the late-Elizabethan culture of young Shakespeare's verse or Hilliard's miniatures. In both, a playful, filigree charm and grace curls around the edges of iron-fisted power.

Lovers of Islamic art with less-than-perfect eyesight will know the strain that close focus on fine carpets, illuminated Qurans and painted ceramics can impose. At a half-way break in the form of a miniature maidan (square), tall screens above the benches display unfolding photo-galleries of the Shah's grandest buildings. The ruler was a dedicated shrine-hopping pilgrim, who in 1601 walked 1,000 kilometres from Isfahan to Mashhad. Resting weary feet and eyes, we feel as well as see his world. If exhibition designs can ever compete for prizes, this would be a formidable contender.

British Museum (020-7323 8181) to 14 Jun

Charles Darwent is away

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments