Sculptors' Drawings, Pangolin London/Kings Place Gallery, London

There's no getting around these sculptors' work – it is stupendously flat. And that is a joy to see

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Where is the front of a sculpture? Where do you stand, where does it stand? Confronted with a new person, we are instinctively drawn to the face. But sculpture is more liberating. Who does not, dwarfed by Michelangelo's clean-limbed David gazing sightlessly into the middle distance, creep round the back for an eyeful of those magnificent hamstrings and fruity buttocks?

When the sculptor abstracts the facial features – Henry Moore leading the charge – feet, belly, head and the very space that they occupy acquire equal prominence. But what happens when sculptors confine themselves to only two dimensions – when there is only a front – is the question answered at this massive exhibition over three floors, jointly staged in King's Cross by Pangolin London and Kings Place Gallery.

From sketches no bigger than your thumb to sprawling explorations on the scale that we associate with big public commissions, the 200-plus works in Sculptors' Drawings and Works on Paper include both sketches for three-dimensional pieces, and drawings that are an end in themselves. And what is striking about many of the finest is that they are stupendously flat.

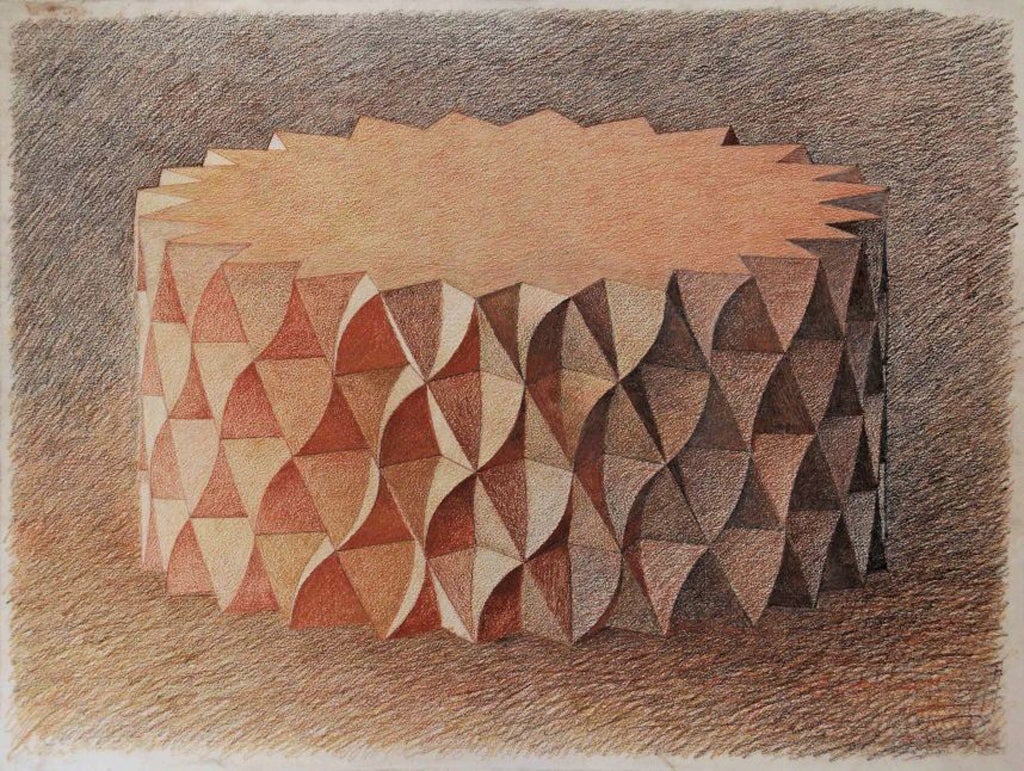

Yes, there are virtuosic exercises in depth and perspective – John Maine's Drum with Undulating Edge, engineering in crayon, Briony Marshall's Fibonacci-inspired Embryo Spiral, her radiating lines enclosing a spidery foetus – but the drawings that take your breath away are those that settle unprotestingly, indeed with relish, into two dimensions.

Small wonder that the galleries chose George Fullard's Head (1961) for the cover of its comprehensive catalogue, a drawing that is almost Bach-like in its capacity to take a simple line and weave it into something inventive and beautiful. With only 14 strokes of the pencil, William Turnbull's Nude (1976) becomes flesh and blood, the woman's arms raised, hair tumbling down her strong back. Lynn Chadwick, whose trademark fused and poised kings and queens grace many a public space, translates easily to paper. We learn that he sometimes created his full-scale sculpture first, and drew afterwards, overturning our expectations of the creative process.

Moore, for his part, admitted that his random jottings took on a life of their own: "I may scribble doodles in a notebook, and within my mind they may become a reclining figure ... Drawing is a means of finding your way about things."

But pen, pencil, crayon and charcoal are not the sculptor's only materials. Sarah Lucas's The Cords of the Sympathetic System pointedly traces the head and lungs entirely in cigarettes. Sokari Douglas Camp's Son and Mum (2009) draws on the wall, its colourful image of the family, with baseball cap and headdress affectionately intertwined, proving to be a painted steel stencil that throws the image in shadow on to the white paint behind with the legend "Obama rocks".

Taxidermy is the emphatically 3D domain of Polly Morgan, who on paper draws not with pencil but with the cremated remains of birds, the ash worked into a dilute glue to create the ink for Study for Harbour (2012). Alan Dun mixes his ink with bronze and iron powder for his touching profile of a printing press, Study for Old Number Six, its simple technology a proud totem of enlightenment. And is there anything blacker on this planet than Richard Serra's paintstick in Untitled (2009), a bottomless, impenetrable puddle, as mighty in its way as his slabs of metal presiding over city squares and galleries?

The colourists have their moment here, too, but it is still texture and line, rather than paint, that engages these artists. Ben Nicholson, entering this arena, one feels, on a technicality, his white reliefs being on the cusp between sculpture and drawing with shadow, gladdens the heart with his Green Jug (1978), colouring the paper, not the object, and zipping the outline of the pot over this green wash. Marino Marini's Two Acrobats with Horse summarises a complex manoeuvre in a few lines and makes it brilliant in a sunny yellow litho, and Bernard Meadows' haunting birds are ambiguously watercoloured with a flood of orangey red: jubilation – or fresh blood?

If all this sounds a little worthy and ascetic, there are also moments of humour and tenderness: Michael Joo draws dozens of mattresses and two chrome peas wedged low down, and envisages himself as the princess asleep on the top, not bothered by the obstacle one jot, but sleeping on, oblivious.

Susie MacMurray, whose sculptures in soft materials – feathers, textiles – are always things of wonder, draws two hairnets at 10 times normal size, turning them into organic objects of mystery and complexity. And, among the many mother-and-child embraces, perhaps none is as moving as Fullard's anxious parent escaping out of the picture, her innocent burden clasped under one arm, its little limbs flapping weightlessly.

There are some horrors: Damien Hirst's nasty scratchings with their floppy anatomy and annoying perspectival ticks quicken the pace rather than the pulse. And one can only recoil from David Bailey's Dead Andy. While its drawing is a tropical explosion of palm-tree hair, the sculpture showing Warhol bursting out of a tin of beans (actually jelly beans) is a nightmare.

More than making up for that aberration, however, is the handful of other sculptures shown with their drawings, and it would have been wonderful if there had been a few more examples of these. Nonetheless, this is an illuminating run around the past 100 years of art, from big hitters to newcomers. Picasso said that drawing was for him a habit, like nail-biting. For the rest of us, it is a gift that most would be happy to have.

'Sculptors' Drawings' (020-7520 1480) to 12 Oct

Critic's Choice

Tate Britain’s autumn blockbuster, Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Avant-Garde, is now open; book for your dose of romance and rebellion, beauty and mythbusting (till 13 Jan). Bringing together 10 international artists to examine concepts of the past, present and future, including Susan Hiller, Vernon Ah Kee and Jeremy Millar, The Future’s Not What it Used to Be is at Cardiff’s Chapter Gallery (till 4 Nov).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments