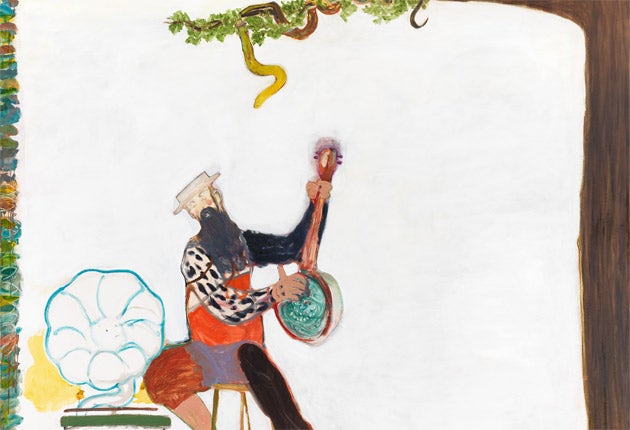

Ryan Mosley, Alison Jacques Gallery, London

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Two years ago, this newspaper talent-spotted a young painter. Ryan Mosley, who is from Chesterfield, that small market town with a crooked spire at its heart, had recently graduated from the Royal College of Art. Now he is enjoying his first solo show at a major West End gallery. What's the fuss all about?

At this time of year, as the rain spits malevolently into your face, the miserable lines of the great Irish poet WB Yeats swim into the mind: "the centre cannot hold/Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world." If you were to look for an antidote to such an apocalyptically gloom-struck message, you would find it in the paintings of Ryan Mosley.

Some painters create worlds of precious stillness. Even when there is a promise of music, it is restrained and decorous. Think of Vermeer, for example. Mosley's paintings inhabit a world of brash, non-stop, cacophonous, shape-shifting carnival. He has a kind of wild recklessness of manner, a crude exuberance. When you walk into a gallery full of his paintings, it is as if you have turned a corner and stepped into the path of a brass band in full flight. There is so much noise and breathless activity in his paintings. Some painters seem to paint, pause, breathe and then paint again. Mosley seems to spend his life running at the canvas, full-tilt.

There are two sizes of paintings in this show, big and small. In mood there is nothing to choose between the big and the small. It is all part of Mosley's world of gleeful unreason. The small paintings tend to feel like details snatched from the larger ones.

You can call these narrative paintings if you like, but they don't tell a story that could be re-told in a sensible fashion. There are figures and objects but they are more often than not bits of figures and objects and at any moment the objects could easily become figures and the figures objects. Things morph into other things. Legs end in heads with Afro wigs.

Here are two favourite motifs: the snake and the cactus. There is something altogether slippery, gaudy and unreliable and unknowable about snakes. All these characteristics seem to appeal to Mosley. Cactuses are spiky and visually rather ridiculous. They seem to be dancing in the air, fisting up and out. Mosley loves dashes of almost unpremeditated wild colour and he likes the idea of menace and mock-menace, the two in combination.

One of the largest paintings is called Southern Banjo. A curious banjo player sits on a stool, crooning to a gramophone with an extravagant horn. Usually it is the gramophone which sings the song. Not in Mosley's topsy-turvy world.

There is something quite willfully uncalculated about this way of making paintings, as if every one starts somewhere quite unexpected and goes on pushing forward until it has finally exhausted its own possibilities.

To 13 February (020 7631 4720) at Alison Jacques Gallery

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments