Naked and the dead: William Burroughs's artwork

A new exhibition showcasing William Burroughs’ other talent – as an artist – is disturbing enough, before you realise the shocking event that fuelled his creativity

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was after the American Beat writer William Burroughs shot his common-law wife Joan Vollmer in the head by accident during a game of William Tell in Mexico City in 1951, rendering her two young children motherless, that his creativity achieved new power.

He said: “I am forced to the appalling conclusion that I would never have become a writer but for Joan’s death... I live with the constant threat of possession, and a constant need to escape from possession, from control. So the death of Joan brought me in contact with the invader, the Ugly Spirit, and manoeuvred me into a lifelong struggle, in which I have had no choice except to write my way out.”

Burroughs was never punished for the crime and his enduring remorse is documented by Barry Miles in a biography that was recently published to celebrate the centenary of his birth. Most famous for novels that fizz and spit at you – particularly Naked Lunch (1959) with its “junk-sick morning” – and for being part of a triumvirate with Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, Burroughs was also a visual artist. Sometimes he would make art with his eyes closed, literally, in order to explore his own psyche rather than to be shown to the public. The visitor to this exhibition should perhaps bear that in mind.

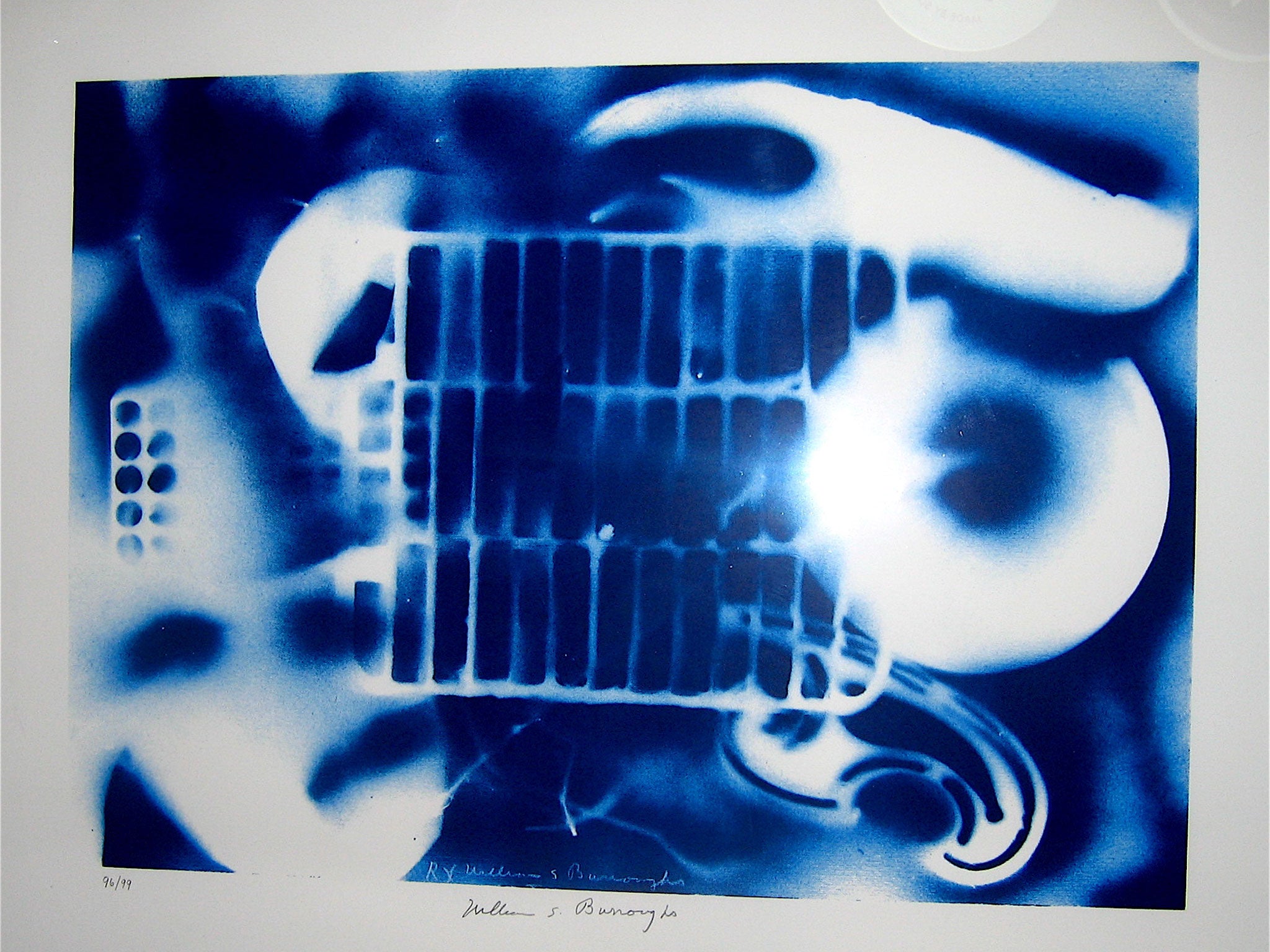

This is a modest selection of mostly paintings – a rougher, more ad hoc complement to the exhibition of Burroughs’ photographs at the Photographers’ Gallery. Would these works be recognised without the myth of their creator? Probably not – but they are fascinating cultural documents, testament to the “rancid magic” (to borrow a phrase from Naked Lunch) which Burroughs continues to trail in his wake. He died in 1997 at – miraculously, given his Herculean drug intake – the age of 83. Most striking and disturbing about this exhibition is the number of works that involve shooting things.

Out of the Closet (1990) is a sculpture comprising a square of aged American plywood, about as big as a TV screen. It is spray painted a range of vivid reds, from cherry to dried blood, and black, which gives the impression the wood has been doused in guts and soot. There are stencils of ghoulish figures with imprecise, wobbly limbs, no features. They are brought into relief by the darkness around them. The figures recall Burroughs’ own self-proclaimed status as “el hombre invisible [the invisible man]”. He famously wore impeccably cut three-piece suits. “Basically, it was because he was gay and he was a junkie,” Miles said in an interview. “He really didn’t want to draw any attention to himself.”

The sculpture is not good. It looks like a piece of goth art, conceived by a disaffected teenager in a garage somewhere in the Midwest. It is crudely angry, Halloweenesque, in love with the dark side. However, it becomes resonant when you look closer and see that the plywood is punctured by two gaping holes, one in the centre and one lower, to the right. The holes have been made with force; the wood has splintered around the edges to look like satanic, jagged teeth. They evoke the screaming mouth of Bacon’s Pope. In fact, the holes are gunshots.

Burroughs was living in Lawrence, Kansas, when he made this sculpture. He was in his early seventies. Miles has described his love of shooting: “One day he noticed the way that the wood had splintered was very interesting, as in a sculptural way… he started to hang cans of spray paint in front of the pieces of wood so when he let rip with his gun the can exploded.” Burroughs would hang the cans of paint above the wood too, which recalls that fatal 1951 game of William Tell. Vollmer had placed a highball glass on top of her head, which Burroughs shot at. He missed.

The power of these artworks lies in their entwinement with his biography. They are vitalistic outbursts, wilfully lethal, boyishly destructive. There is a long history of combining the forces of Eros and Thanatos, life and death, in transgressive art. They bring to mind a toddler torturing insects. The shotgun paintings are akin to French artist Niki de Saint Phalle’s 1960s Shooting Pictures, for which she filled polythene bags of paint, enclosed them in plaster, and then invited people – including fellow artists Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns – to shoot. The paint exploded over the backgrounds in abstract expressionist chaos. Saint Phalle stopped making the works in 1963, however, because she said: “I had become addicted to shooting, like one becomes addicted to a drug.”

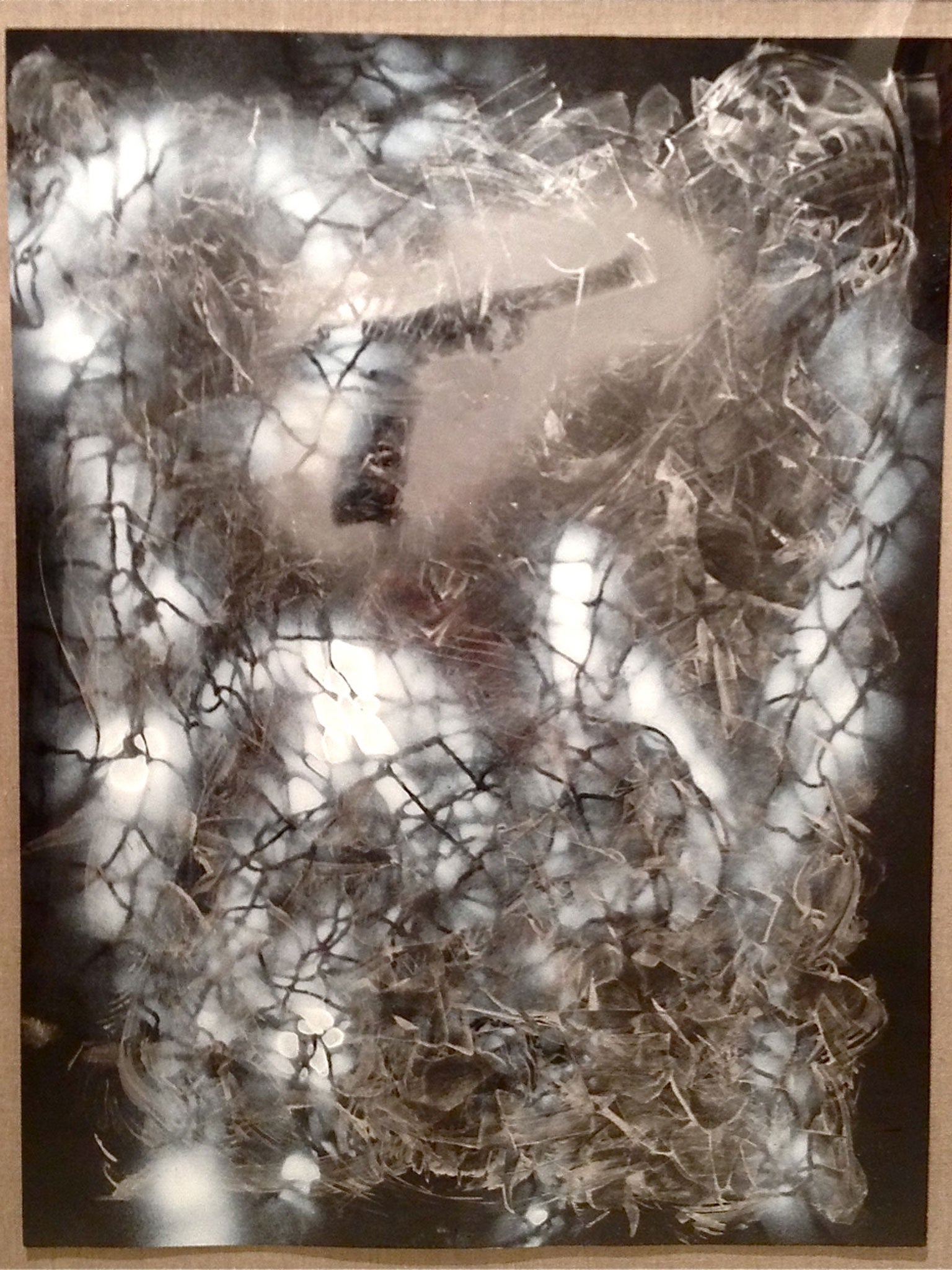

The statement chimes with Burroughs, whose output is infused with drug addiction. Indeed, some of the more charming works here were possibly made by dipping magic mushrooms in paint and wiping them over the surface of manila folders. The File-Folder series were made from 1988 to 1992. They began when Burroughs used the outside of the folders, in which he stored his writings, as colour palettes for paintings. Like so much of Burroughs’ work, they started by accident. They are small abstract expressionist paintings in swooping red and purple strokes, forceful yet elegant. They are the best works here, indebted to the calligraphic paintings of Burroughs’ long-time friend, Brion Gysin.

It was Gysin who introduced Burroughs to the cut-up method for which he became famous. Following Dada and Surrealism, Burroughs rearranged bits of text and image to create new orders of meaning (or no meaning, depending on how you look at it) in both writing and visual art. He inspired punk writers like Kathy Acker. It’s a shame that none of his cut-up collages are included in this exhibition.

Instead, the theme of shooting overwhelms. Next to a portrait of Burroughs looking like a stony-faced undertaker on the Rue de Seine, there is a portrait that he made in 1993 of his dentist. He hated his dentist. This is clear. It is a large child-like drawing in black felt marker, redolent of the Mexican Day of the Dead. Presumably by way of revenge for the pain inflicted on Burroughs, the dentist’s mouth is a mangled void, broken dashes for teeth. He has “cancelled eyes”, to borrow another phrase from Naked Lunch. He has been marked with a “curse number” – 23 – and the canvas has been shot at 23 times with a gun. Again, the work assumes a different meaning when you think of Vollmer.

The obsession continues elsewhere: there is a red florescent spray-painted image from 1989, covered in stencils of what look like penises, pointing in all directions. This is confirmed by the title: Red Pricks. They could also be guns, drawing the old parallel: phallus = weapon = pen = power. It is a trashy piece of art, but a potent piece of ideology.

The art historian Griselda Pollock has written about “killing men and dying women”. The phrase is relevant to the history of genius. Often the woman must “die” – be metaphorically dominated or overcome – in order for the man to feel sufficiently potent to create. In other words, art requires sacrifice, and that sacrifice is historically feminine. In a horrifyingly literal way, Burroughs seems to embody this theory.

Burroughs was a visionary and renegade, but he was also a Harvard graduate from a wealthy family who got away with homicide because his brother bribed the authorities in Mexico. He only spent 13 days in jail for killing Vollmer. This fact cannot be overlooked as a mere biographical detail. In this light, his insistence that “everything is permitted” seems more aligned to the entitled hedonism of the Bullingdon Club than the counter-cultural dawn. The fanatical emphasis on guns in this exhibition might be a sign of guilt, the motif of sin repeated ad nauseam until the end of his long life. Or it might be the arrogance of a man protected from the law by privilege.

William Burroughs 100, Riflemaker Gallery, London W1 (020 7439 0000) to 29 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments