Matisse in the Studio, Royal Academy, London, review: gorgeous and surprisingly revealing

The RA's new exhibition beckons us into the hedonistic cocoon of the artist's studio, where he surrounded himself by objects he considered his muses

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

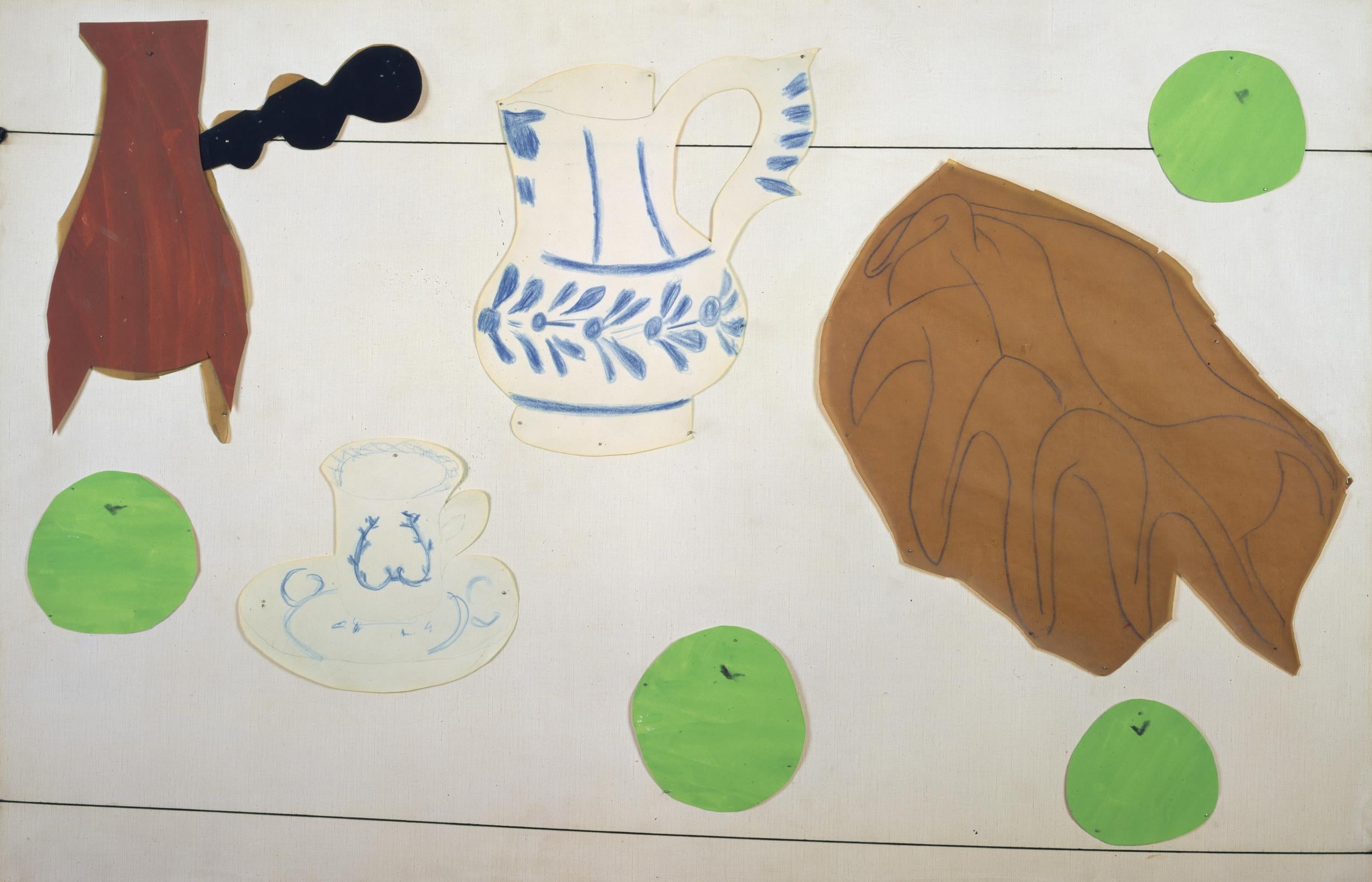

Your support makes all the difference.This gorgeous and surprisingly revealing exhibition allows us to experience the intimate thought processes of Henri Matisse as he worked in the hedonistic cocoon of his studio, surrounded by the many objects that served as his constant personal muses. Amassed from his travels, antique shops and flea markets, the 35 objects in the exhibition are shown alongside 65 significant works of art, the latter embracing the many mediums that Matisse explored throughout his long life (1869-1954) – painting, sculpture, drawing, print and, uniquely, his gouache cut-outs.

While two world wars savagely raged outside and models came and went, Matisse created beautiful studios that became complete environments for his own adventures in art and design, filled with furniture, textiles, African sculpture, chocolate pots and more. An evocative photograph in the first room of the exhibition shows the elderly Matisse in his Villa La Rêve in Vence (1944), a picture of tranquillity surrounded by beloved objects and vases of flowers.

The exhibition is curated around the various objects that Matisse used in his art, which he compared to actors. "A good actor can have a part in ten different plays," he explained: "an object can play a role in ten different pictures." In this sense, the objects are much more than bit-players, as Matisse transforms them according to their particular context. A green blown-glass Andalusian vase, which appears in several works, can hold Safrano roses, while at the same time playing a dominant role in what Matisse was searching for: "a sympathy between communing objects."

The star of the second room is a flamboyant 19th-century wooden Venetian chair, which Matisse declared himself to be obsessed by. Its voluptuous form, made up of painted and gilded shells (seat and back), reptilian creatures (arms), and seahorses (legs) also becomes a swirling container for fruit and flowers. In one picture the chair dances with a table, made up of similar arabesques; in another it becomes an anthropomorphic personalised object, its crouching form sporting a small boutonnière of white blossoms.

The central rooms show Matisse grappling with African sculpture – from as early as 1906 – as he creates difficult, abstract tough nudes, together with strikingly abstract faces that mask and reveal "hidden feelings". Vitrines displaying the actual figures and masks he collected, including a wonderful Hellenistic torso, nuance our understanding of Matisse’s lifelong interest in abstracting the human form.

The final rooms explore the studio as theatre, with a selection of some fine Islamic artefacts – a brass brazier, an octagonal chair with exquisite painted decoration, and splendid fabric hangings that replicate fret-wood screens. These ‘props’ appear again and again in Matisse’s works of the 1920s, evoking the languid world of the Odalisque (concubine) but also creating an hermetic world of pattern, colour and design. A large Chinese calligraphic panel becomes the starting point for the preoccupations of Matisse’s last years as, incapacitated by cancer, he turned to the design of decorative objects and also created his revolutionary paper cut-outs, which attain "a form filtered to its essentials". While the term ‘decorative’ is often used pejoratively, Matisse’s absorbing approach to the objects and forms that he used demonstrate just how profound ‘decorative’ can be.

'Matisse in the Studio' is at the Royal Academy of Arts, 5 August to 12 November

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments