Mantegna and Bellini, National Gallery, review: The new exhibition shows both Renaissance painters to be distinct masters of their craft

The quality of the artist's colours inspired the naming of the Bellini cocktail

Sibling rivalry can, as in the case of the Renaissance painters Giovanni Bellini and Andrea Mantegna, become an inspiration, which leads to greater things. They were brothers by marriage – Mantegna married Bellini’s sister, Nicolosia, in 1453. With this alliance, he ingratiated himself into Venice’s most prominent artistic family.

A new exhibition, Mantegna and Bellini, at the National Gallery brings these brothers-in-law side by side once again. By showing how they each tackled the same themes, particularly in the first decade when they worked together, the viewer is encouraged to notice where these masters of Renaissance painting converge, and where they remain distinct.

Bellini had only been painting six or so years when Mantegna, with 20 years experience, arrived in his father Jacopo’s workshop. In the early years he follows Mantegna’s themes, always religious. Later, he comes into his own.

Mantegna, the son of a carpenter and an artistic prodigy, was the master of perspective, creating three dimensions which are so convincing that they almost seem to disappear into the walls. Every corner of his paintings is covered with minute detail, showing his ability to paint facial hair, leaves, rocks and the winding of paths and rivers, which vanish into the background.

Bellini had a broader stroke, and was more of a colourist, with an ability to recreate the pink light of dawn, to leave a landscape open and contemplative, and depict water that looks good enough to drink or dive into. The quality of his colours inspired the naming of the Bellini cocktail: when Guiseppe Cipriani first mixed prosecco with peach nectar, the colour reminded him of a Bellini painting.

Mantegna’s painting of The Presentation of Christ in The Temple from 1454 is dramatic. Simeon’s beard is a perfect waterfall of distinct curls. His infant Christ, with the strange part-doll, part-adult features that all Renaissance babies seem afflicted by, is swaddled masterfully in bandages that reveal every curve and crease.

Bellini’s version follows the same composition. But his Simeon has an amorphous beard, like a cloud hanging from his face. The overall feel is muted, with facial expressions that are more expressive. It is quieter and emotional – a subtle display of skill.

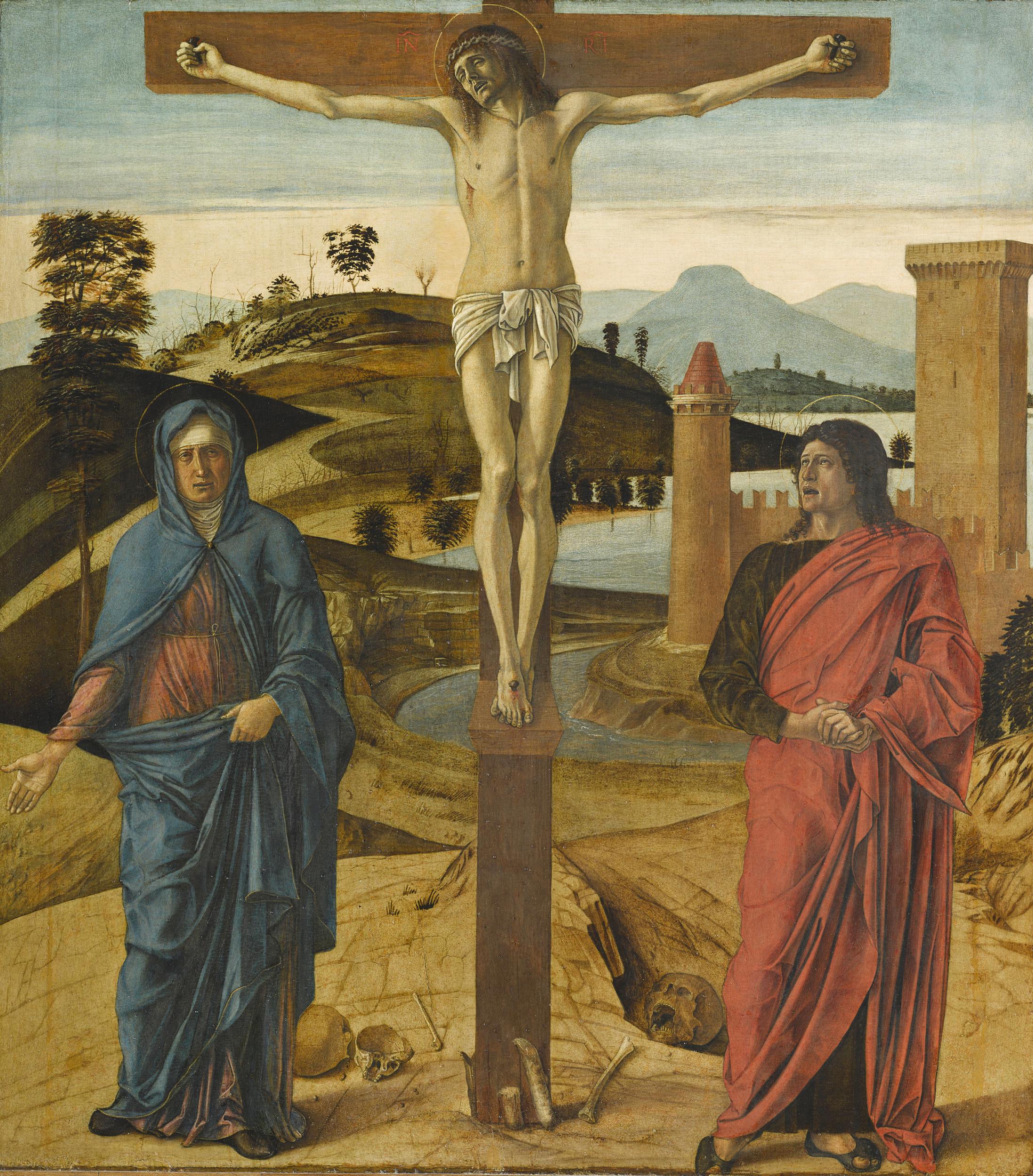

Bellini’s bodies, in later depictions of Christ, are softer and fleshier than those by Mantegna. One feels the weight and warmth of recently dead flesh, of limp muscles and collapsed bones. Mantegna’s bodies are like carved marble, every abdominal muscle and bicep defined. They are as rigid as Classical sculpture.

Mantegna’s interest in Classicism, encouraged during his time as painter to the wealthy Gonzaga family, develops later on. His subjects move from the purely religious to themes of antiquity: Samson and Delilah, Caesar.

The final rooms in the galleries offer the most spectacular paintings by each artist. Bellini, using oil paint, which Mantegna never did, reveals his flair in a private commission of Doge Leonardo Loredan, painted in 1501-02. No longer in profile, the sitter faces us, a palette in varying shades of gold, nut brown, white and blue. The richness of the surface, of gold brocade fabric, contrasts with the serenity of the sitter’s face. It is a stylish and simple portrait, elegant in its restraint.

Mantegna’s coup de grace shows Minerva expelling the Vices from the Garden of Virtue. The detailing – every blade of grass, the curls on a baby’s head – is outlined. The narrative is dense and complicated. Painted at the same time as Bellini’s portrait, it shows how the two have stepped into their distinct styles. By now, any need for rivalry must have surely dissipated. Both are masters of their craft.

Mantegna and Bellini is at the National Gallery from 1 October to 27 January 2019

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks