Kitaj: Portraits and Reflections, Abbot Hall Gallery, Kendal

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The American painter R B Kitaj, long resident in London, left England in grief-stricken disgust after critics had panned his retrospective at the Tate Gallery in 1994. He died at his last home in Los Angeles in 2007. This mini-retrospective at the ever enterprising Abbot Hall Gallery in Cumbria is the first extensive sighting of his works in Britain since his death.

Was he an American or a European painter? Six of one and half a dozen of other. There is evidence of his near idolatry of European painting everywhere in this show. He re-paints Van Gogh, Cézanne and Rembrandt in his own image, reworking their motifs – he wants to see the world through their eyes. And yet he also cleaves to his Americanness. He paints with a kind of vibrant, outrageously colourful insouciance when the mood takes him. He is a cartoony collagiste in spirit, who seems to be forever tearing his images apart in order to recombine them in ways that often surprise or affront us. He respects no division between painting and drawing. His works look and feel, in the feverishness of their attack, like drawn paintings or painted drawings. He is above all things else a painter of the human figure, but his treatment of the human is far removed from that of a painter like Lucian Freud.

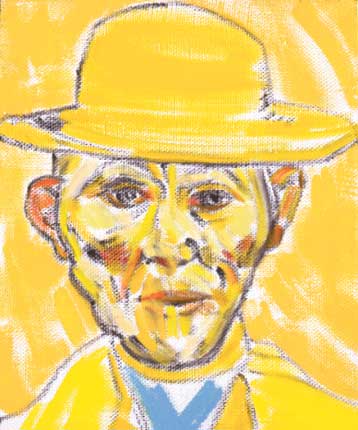

Kitaj has no particular interest in crooning over the perishability of the flesh. His human beings are engaged in significant activities that identify them as protagonists in particular worlds. Kitaj, for all his modernness, is something of a traditionalist in his love of oil paints, pastels, charcoal, but he also amalgamates all three in unexpected ways. He is a modern who also wants to be old. He is intensely autobiographical, but he wants his musings to be out in the world. He wants his works to look as if they are part of an ongoing debate about politics and cultural identity. And yet he is also utterly idiosyncratic. He paints awkward, collage-like things that allude to politics and literature and try to claim the space that those disciplines occupy, but he often looks and feels wild, obscure and wayward in the way that he chooses to amalgamate text and image. His extraordinarily exuberant use of colour is what catches our eye time and again – the cymbal clash of these violent yellows against that magenta.

He is also utterly besotted by his own Jewish identity. In painting after painting he seems to be asking himself what this means for his vocation as a painter. Does it give him a certain kind of hallowed awkwardness? He certainly seems to wish to claim that. In an extraordinary late painting called The Beautiful Dress, he presents himself as a kind of dancing schlemiel. It is the dress itself that seduces our eye, all those brilliant, whirling lozenges of colour. His last paintings are small and square and painted on canvas with a coarse weave. Several of them are self-portraits in which he depicts himself through the images of other painters, notably Cézanne and Rembrandt. They are pared to the bone, as if the simpler the image, the more truly defining it will be. He was always a man casting around for an identity, eager to demonstrate his intellectual gravity. He never stopped looking until death stopped him looking.

To 8 October (01539 722464)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments