Keeping It Real: Subversive Abstraction, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London

This is the real thing – putrid cheese and all

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Dieter Roth's Grosse Landschaft (Big Landscape) seems strangely familiar, a golden sun setting on a brown field, some German take, perhaps, on Gustave Moreau.

Then it strikes you that Roth's sunset is familiar not from art history but from the deli counter, it being made of cheese. The work is now 40 years old, so it is difficult to say what kind of cheese has been used – a nice, round gelber Käse, maybe? – although its rotting has been coincidentally painterly. And why not? Raphael worked in egg yolk, after all, and most painters use linseed oil.

To make things sicklier, Roth has pressed his cheese on to roofing felt – yuck – and squashed the lot behind a clear plastic membrane, giving his landscape the puckered air of a particularly unhygienic supermarket. (Roth also liked to be known as Dieter Rot.) Its fascination with food fits Grosse Landschaft into a strain in modern German art which remembered postwar hunger; Roth's use of felt steers us towards Joseph Beuys, who likewise had a yen for saturated fats. It is thus the representation not of one but of many things, a history painting with a number of histories. And Grosse Landschaft is also a picture of nothing at all, a putrid cheese squashed against clear plastic, which is presumably why Roth's work is in a show at the Whitechapel called Subversive Abstraction.

What is abstraction? And, more narrowly, how long is a piece of string? To the English of the 1920s, Paul Nash was an abstract artist, although he painted landscapes that were clearly landscapes and had names such as Stone Cliff. One obvious way to subvert abstraction is to paint known things and then call them abstract, or to make abstracts out of materials that are recognisable as objects: cheeses, say. This is the opposite of abstraction as we more usually know it, a style whose aim is to look like nothing at all – the anti-representational rectangles of Mondrian, say, or the flicks and drips of a Jackson Pollock. Roth's allusive abstraction may sound like a case of having your cheese and eating it, but then that is rather the point.

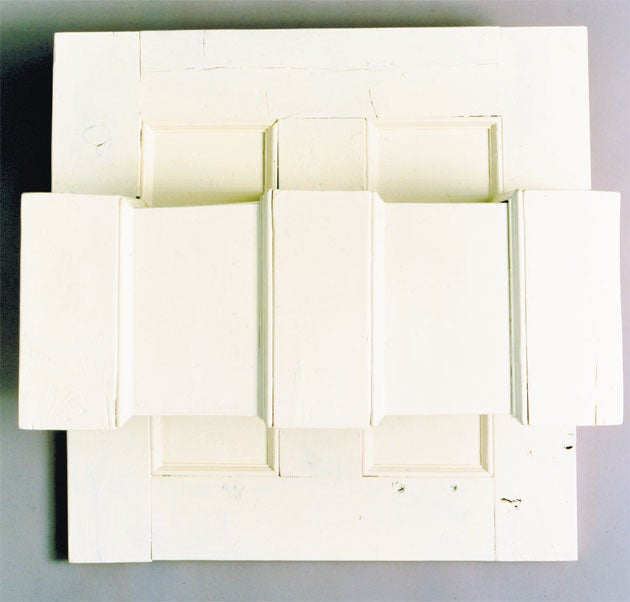

Take Robert Gober's Unfolding Door. Gober's sculpture is more or less what it says it is, a traditional white-painted wooden door sliced up, reassembled – sideways-on, it looks like a swastika – and hung on a wall. If it wasn't a door, it might be a Donald Judd, a piece of Minimalist sculpture. But it is, insistently, a door. A Judd wall piece may look like a shelf, but it doesn't mean to; Gober's sculpture looks like a door, and it does. Why?

It's a question that runs through the Whitechapel's show. The second in a series of four called Keeping It Real, Subversive Abstraction is drawn from the collection of a Greek yogurt millionaire called D Daskalopoulos. Food is a visceral thing to have made your money in, and Daskalopoulos's collection seems commensurately gutsy. Not for him the cerebral agonising of Neo-Geo Abstractionists such as Tomma Abts, but an (occasionally cheesy) abstraction which starts from the known object. Thus Mike Kelley's Transplant consists of three rag rugs with toy pooches on them made out of scraps of fabric; here a yellow gingham leg, there a Laura Ashley tail. Part of the uncanniness of Kelley's work lies in a process of what you might call de-representation, making familiar things look unfamiliar, the representational feel abstract. So, too, with the space capsule/hot-water boiler of Nikos Kessanlis, an artist I'd always thought of as a painter but who seems to have gone in for a kind of Hellenic Arte Povera sculpting as well.

The problem with all of this – a niggling one only – is that of intent. I'd imagine that Mr Daskalopoulos collects things he likes, but I'd rather doubt that he starts off by saying, "Today I'm going to buy something that subverts abstraction." That spin on his collection, or at least this part of it, comes from the curators of Subversive Abstraction. In these anti-elitist days, you can't really put on a show called Loans from the D Daskalopoulos Collection. Things have got to be contextualised, de-personalised. And so the Whitechapel has squeezed the work to fit a theory, convincingly so most of the time but not all of it. Why does Daniel Subkoff's slashed-canvas canvas count as subversive abstraction? Search me. But this is a nice show, and a clever one, and I should go if I were you.

To 5 Dec (020-7522 7878).

Next week

Charles Darwent seeks the definitive Monet at the Grand Palais, Paris

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments