Hannah Höch, Whitechapel Gallery, art review

Hannah Höch was a pioneer in Berlin's Dadaist movement of the 1920s. As a feminist and lesbian, she was later to clash with the Nazis, but her work remained joyful, as Adrian Hamilton discovers at a long-overdue retrospective

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

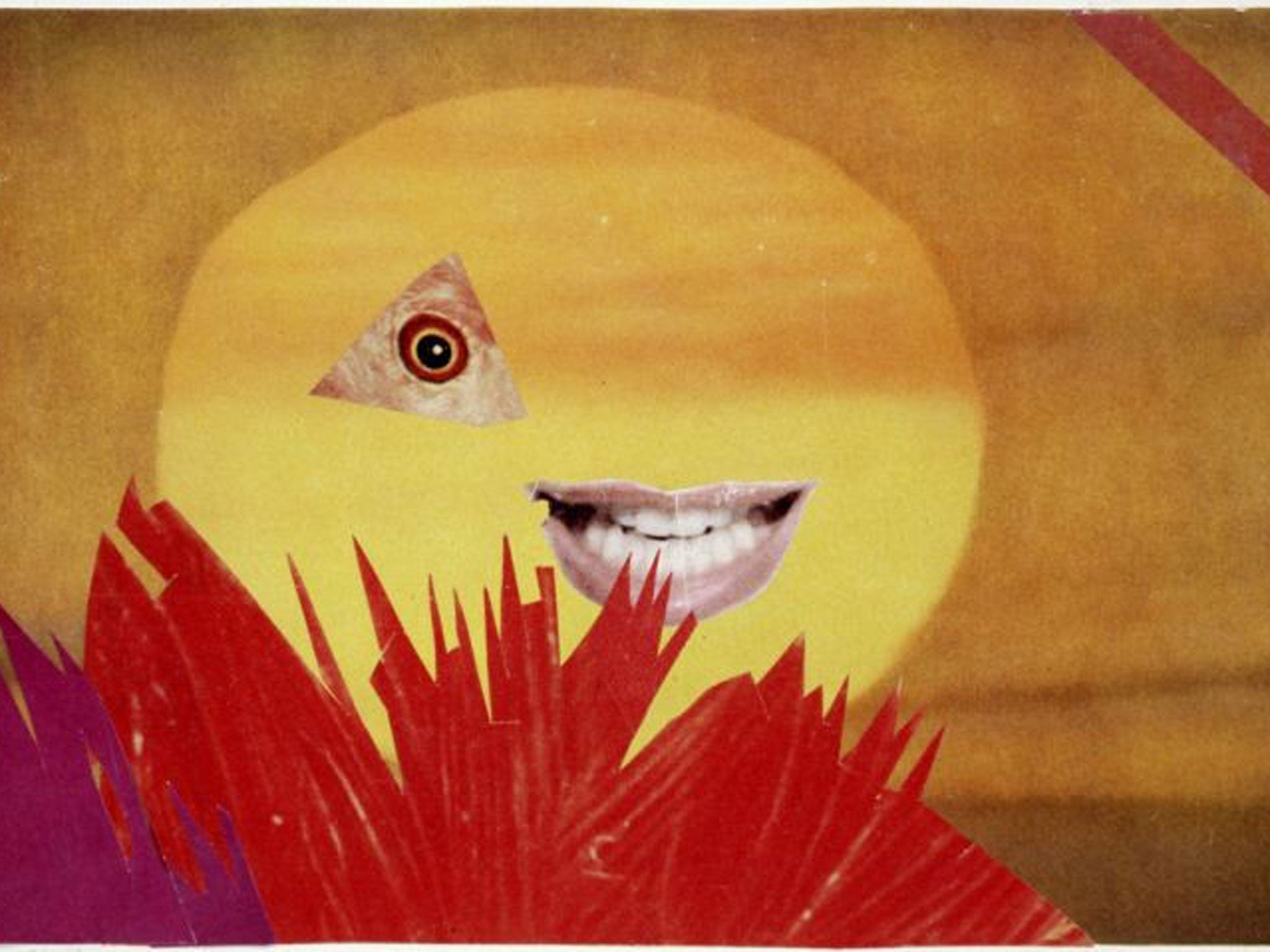

Your support makes all the difference.“Hannah Höch the Dadaist” is the way that this German artist is usually pigeon-holed in art history. And indeed she was a leading member of the movement in Berlin in the 1920s, full of the calls for artistic revolution, the rejection of all that had gone before, the hectic partying and the collage works which made this movement so energetic and so productive.

And yet, Höch, one of the few women in the movement, was always too much her own person and too much a feminist ever really to be constrained by the jokey, form-obsessed art of strict Dadaist theory still less of the surrealist philosophy which she admired. She certainly subscribed to the tenets of an art which broke free of the traditions of fine art. She embraced with huge enthusiasm the photomontages which were the main mode of visual expression of the German Dadaists. And she was an intimate of the major figures of the movement,

And yet, going around the exhibition of her work at the Whitechapel, one is constantly struck by how personal was her vision. Even in her most abstract and rigorously arranged works there is a romantic and at times quite feminine sensibility at work. She may have declared her purpose formally to push the boundaries of what was considered art into new directions but at the back of it there is nearly always something she is trying to say about the human condition and, especially, that of women's.

The Whitehall exhibition is the first major British show covering this brilliant and long-neglected artist's work, a mark of just how slow this country has been to recognise the wealth of German art in the 20th century. It concentrates on her collages and works on paper by which she is best known. Left out are her prolific output of oils and the drawings which she executed with such facility.

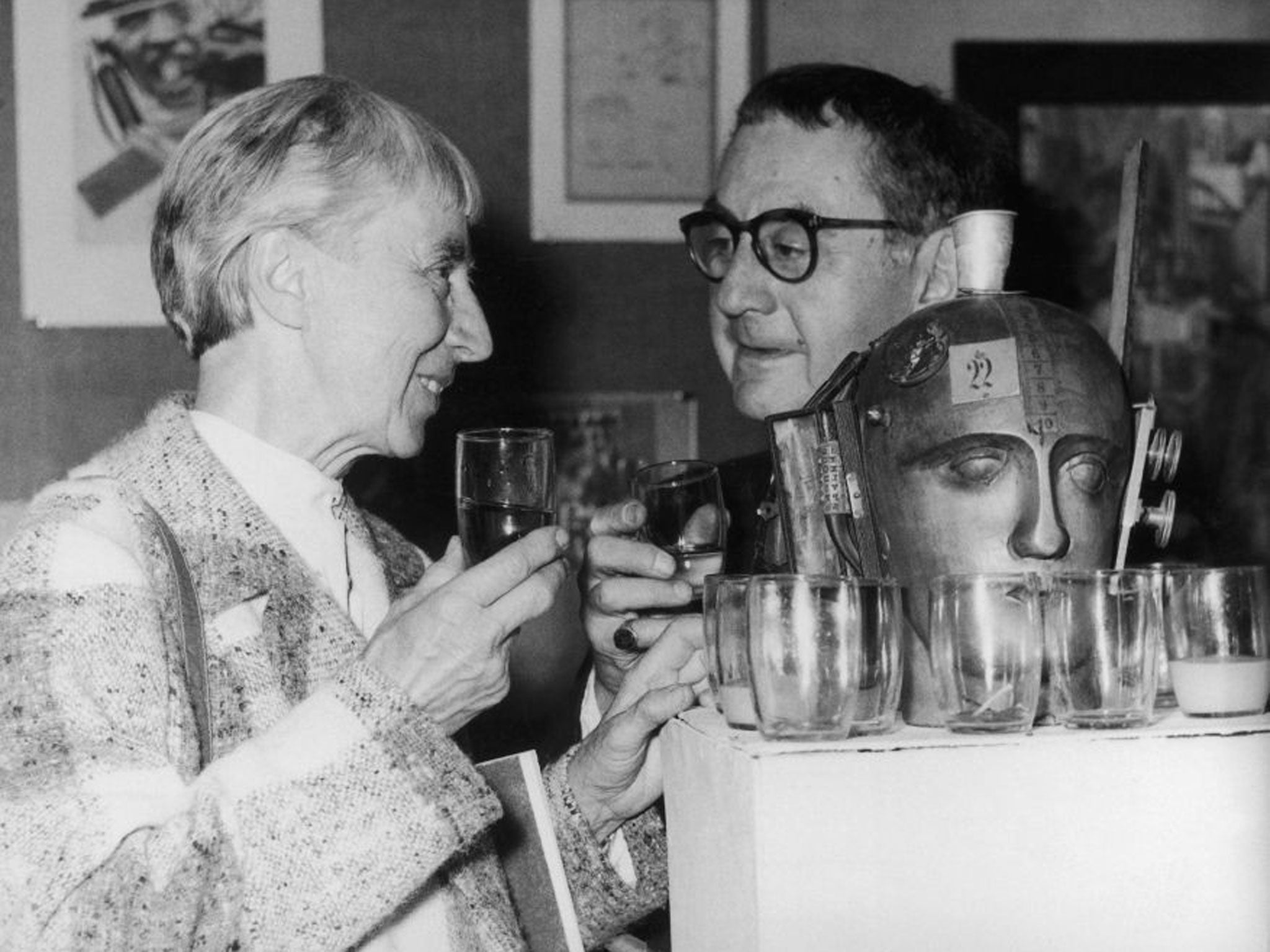

If that makes it difficult for the viewer to judge the artist in the round, however, it does allow a comprehensive and constantly exciting display of the works on which her reputation lies. In a revealing short film interview made in 1966 at the end of the exhibition, the 75-year-old artist explains that she always finished a drawing in one sitting, but a collage took several separate workings, starting with an image, working out a theme and then finding the photographic images from magazines and elsewhere to complete the composition.

What made her so good at the task was partly her training in crafts, including embroidery, pattern-making and textiles, at the School of Applied Arts and its Museum in Berlin and then her job as pattern designer at the major publisher of women's magazines, Ullstein Verlag. “But you, craftswomen, modern women, she declared in a splendidly grandiloquent call in the magazine Embroidery and Lace in 1918 ”who feel that your spirit is in your work, who are determined to lay claim to your rights (economic and moral)... at least you should know that your embroidery work is a documentation of your own era.“

It was a pronouncement not just of intent but very much in the spirit of the times. Born in 1889, Hannah Höch went through two world wars and the prolonged periods of economic distress and rebuilding which were their consequences. The experiences were quite different. In the intellectual ferment of Germany's Roaring Twenties which followed the First World War, the mood (except among those who had fought in it) was one of release from the past mistakes and clear horizons of a new world to be created out of its ashes. Hoch, who always tended towards anarchism rather than the communism of many in her circle, responded at first with some wonderfully witty and scabrous photomontages attacking bankers and ridiculing men in the family and in power. Adding watercolour and ink to collage, she seizes the spirit of the times with some joyously satirical collages of Coquette and the Singer and some open explorations of her own complicated sexuality.

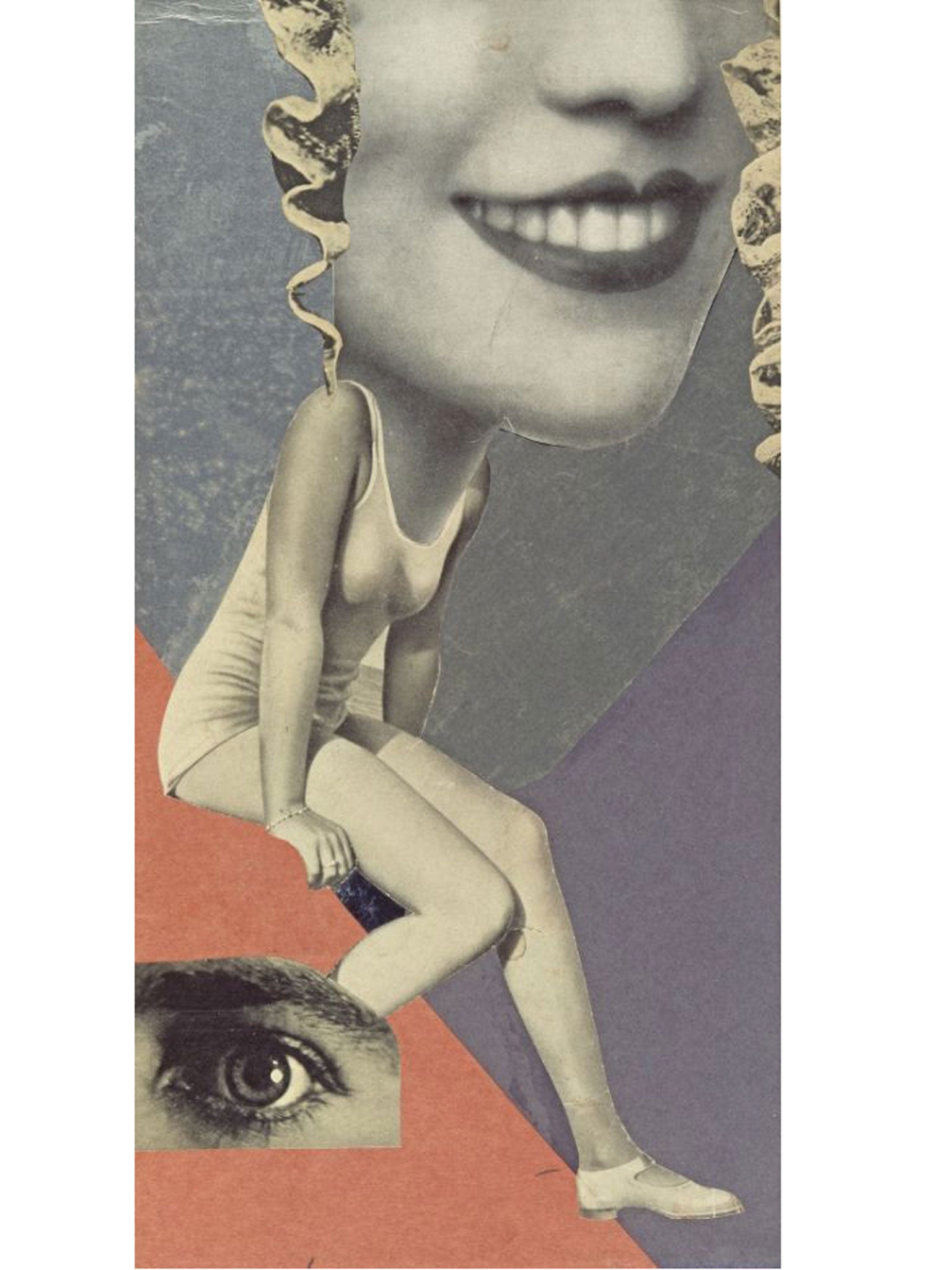

A 10-year relationship with the Dutch Dadaist poet, Mathilda Brugman, and visits away from Berlin brought a change in mood as aesthetics. Höch became increasingly interested in collages as a means of representing the fragmentary and multi-faceted nature of a life, particularly a woman's. In a remarkable, and justly famous, series, (Untitled) [From an Ethnographic Museum], she uses the photographic images of primitive statues in museums and from magazines and pastes on contemporary heads and body parts. The result is an astonishingly subtle and challenging portrayal of what makes up the human and gender in the modern world. It's quite brilliant but also intriguing in its layered meaning.

![Untitled [From an Ethnographic Museum] (1930) Collection of IFA, Stuttgart](https://static.the-independent.com/s3fs-public/thumbnails/image/2014/01/19/18/dada-2.jpg)

The rise of Hitler and the outbreak of the Second World War had a terrible dampening effect on Höch. Although she was not on display in the infamous exhibition of Degenerate Art in 1937, her close association with the leftwing Dadaist group, her lesbian relationship and her assertive feminist position made her unacceptable to the Nazis, forbidden to show her work and spied on. Using an inheritance and marrying a man half her age and of questionable sexuality for the duration of the war, she retreated to a small house outside Berlin and kept herself to herself while many of her colleagues fled abroad to keep the Dadaist standard flying in the US.

It was with relief and “calmness” that she greeted the Allied victory and was allowed to exhibit her work again. A first collage in 1945 is called Dove of Peace and shows the still small bird rising above the iron tubes of war and a circle of construction. Her response to the postwar was both personal and to an extent introverted. Horrified by what man had done and drawn increasingly back to nature as the ultimate source of beauty, her collages became increasingly abstract and frequently disturbing. “Phantasms” she called them and described the resulting fantastic art not as escapism but an “attacks” on the reality that others accepted around her.

The Whitechapel is keen on Höch's postwar art, which has always been overshadowed by here more experimental and joyous interwar work, and has given over its upper galleries to the collages from her show in 1945 to her death in 1978. They are right. The fascination of Höch's art is the tension between the formal and the emotional and her collages after the Second World War give full rein to both. The colours grow brighter but the imagery, when it is recognisable, is more urgent. Journey into the Unknown from 1956 has a knife blade searing upwards through waving weeds, Synthetic Flowers (Propeller Thistles) from 1952 is literally that, thistles with propeller blades pushing towards you. Swamp Spirit of 1961 and The Evil Ones in the Foreground are completely abstract in their organic-shaped imagery but totally emotional in their effect, as she reaches into her own mind to find a combination and juxtaposition of the spirit she wants to express.

In the end, she was too self-examining to become entirely abstract. In the filmed interview she talks of seeking the archetypes of humanity in her drawing in a manner that harked back to the Modernism and Surrealism of her early years. In her collages she became almost Pop in her use of bright imagery from magazine advertising. She revisited her Dadaist years, making collages of women that were still challenging but also celebratory. A final large-scale collage from 1972-3, Life Portrait, examines her own life through myriad photos of time, place and her own face at various stages.

The Whitechapel exhibition is properly respectful, with an excellent catalogue and spacious display. But it is also enlivening. Hoch's collages are compulsive and endlessly rewarding in their detail as their force. Through it all, you sense a women pushing at the boundaries of her art to find a way of expressing the contradictions in her own makeup, between a gay spirit and a darkening view of society around and between the ideal of beauty and the messy realities of individual life. She should be far better known in this country. The Whitechapel has done her proud.

Hannah Höch, Whitechapel Gallery, London E1 (020 7522 7888) to 23 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments