Hand-Drawn London, Museum of London

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Maps lie. Or at least, the people who make maps lie. They use maps to show what they want to show, to say what they want to say. They make the Tube network less accurate but more navigable. They squeeze Africa and expand Europe. Even the London A-Z fibs, exaggerating the thickness of streets and shrinking parks to a green speck. Maps lie, but usually for a reason and often rather beautifully.

Recently, the Londonist website asked their readers to lie. They wanted hand-drawn maps of London to see how Londoners would reimagine their city if given some pens and a blank piece of paper. What would they include? What would they leave out? The results were so impressive that 11 have been put on display at the Museum of London. Collectively, they illustrate the way people personalise public space, physically imprinting it with their own thoughts and memories as a way of making sense of a vast, complex and unknowable city.

Harriet McDougall, for instance, portrays New Cross stripped of streets and playing up the green spaces, transforming this seemingly unattractive inner-city suburb into a rural idyll, much like the one she left behind in Norfolk. Similarly, Flory Leow's wonderful 4 Months off the Boat depicts the area of Bloomsbury around UCL that has become her playground as a student. Areas beyond the border are marked "The (as yet) Unknown". Bloomsbury is still a large space, however, and inside it much has happened, so Leow has annotated the map with her experiences of different places. A small, sad love story unfolds, starting at the cinema where "we held hands" and ending in the square where "You said, 'I can't continue this relationship anymore.'"

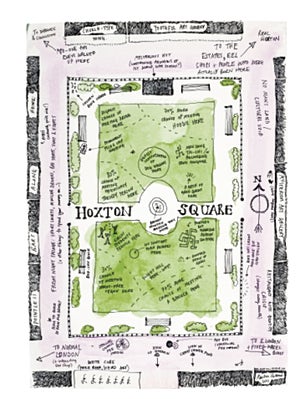

These two maps are the city as seen by outsiders: an attempt to simplify and tame a relatively large area. An insider's view comes from Martin Usborne's witty watercolour of Hoxton Square – one small patch of land the artist has obviously scrutinised for years. Usborne knows the spot in the square that is never touched by sunlight, the corner that is frequented by wheat-free vegans, where to find the sleeping Polish drunk and which direction to head in if you are looking for "real London".

Other artists use London as a base for thematic maps. Julia Forte's pencil drawing examines London firsts, from the first sandwich to the first demonstration of television. Paula Simoes has mapped selected toilets of London, from the egg-shaped loos in a Mayfair restaurant to the paperless toilets at a Japanese bar in Farringdon. A wonderful figurative map comes from Liam Roberts, who sees Brixton as a tree, with the thick trunk of Brixton Road growing from the Thames and spreading branches to Stockwell, Loughborough Junction, Tulse Hill and Herne Hill. Off these branches hang fruit, each representing a pub or bar. Appropriately, it looks like a woodcut.

Hardest to define is Alexander Schmidt's map of Hackney, which portrays individual buildings but no street names in an unfolding repetitive pattern. It's disorienting and impersonal, and although it's relatively small it looks – much like London itself – as if it could go on for ever. That seems an appropriate way to end an exhibition that does much to demonstrate the potential power of the small show in a world dominated by the blockbuster.

To 11 September (020 7001 9844)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments