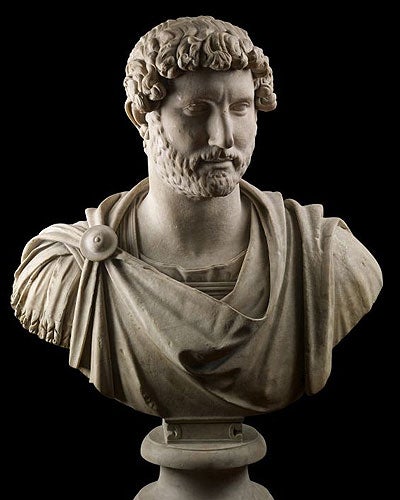

First Night: Hadrian, British Museum, London

Sex, rebellion, wealth... the unseen Hadrian

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For many people, the thought of an exhibition full of white marble Roman statues might seem boring. But this promised blockbuster at the British Museum is anything but. It has sex, rebellions, wealth and intrigue, and best of all it has artefacts that have never been seen before.

At the opening of the exhibition is a real showstopper, the magnificent marble head, leg and foot with sandal from a colossal statue of Hadrian excavated at Sagalassos, south-west Turkey, only a year ago. This is the first time it has been seen. It is easy to think of Roman statues as idealised and generic, but this is thought definitely to be Hadrian, not only because of the hair and the beard, but because of deep characteristic creases in his earlobe that are the sign of heart disease. Another remarkable piece is a bronze head recovered from the Thames near the old London Bridge in 1834. This, too, has Hadrian's characteristic earlobe creases and is a potent reminder that London was once a Roman city.

A complex and a gifted individual, Hadrian was intellectually talented and energetic, with a passion for Greek culture that earned him the nickname "graeculus", or "little Greekling". While he was a hardened military man, he was also gay and seemed to fall genuinely in love with the "shameless and scandalous boy", the young Greek Antinous, for whom he built the city of Antinoopolis on the banks of the Nile, following his death by drowning in rather murky circumstances. One of the most beautiful exhibits is the magnificent head of Antinous from a villa near Friscati. With his strong nose, sensual mouth and ringlets it is easy to see why Hadrian fell for him.

Hadrian, Emperor from AD117 to 138, was not destined to rule. Born in Rome "on the ninth day before the kalends of February in the seventh consulship of Vesperian and the fifth of Titus", he was, on the death of his father, adopted by a distant relative, Trajan, a successful general during a period of simmering conflict. Trajan had himself been adopted by the elderly and childless Emperor Nerva. When Nerva died, Hadrian's succession was assured.

Hadrian was to transform the character of the Roman Empire, thus ensuring its survival for centuries. But his empire was characterised by revolts in many quarters.

One of the most infamous was in the province of Judea in AD132, when the Jewish population rose up.

The Bar Kokhba rebellion became known as "the first Holocaust". The rebels and members of the Jewish civilian population fled to underground hideouts and caves in the Judaen desert. There the arid climate preserved a remarkble array of artefacts. On show here are everything from mirrors and house keys to a glass bowl that is so pristine it could have just been bought in John Lewis. But most important from an archaeological perspective, are the handwritten documents detailing the event that were found in the caves.

Hadrian built himself an extraordinary villa east of Rome. It is the largest known from the Roman world, a vast architectural playground with enough baths and theatres for a small town, a model of which can be seen in the exhibition. It was this passion for architecture that prompted contemporary historians to say "he built something in almost every city".

He may have been a military dictator on a grand scale but it is his architectural legacy and contributions to buildings such as the Pantheon in Rome that are his continuing gift to the modern world. The remarkable peacocks made of gilded bronze from his mausoleum and then used by the Popes to decorate a fountain outside St Peter give some idea of his charisma.

This may not quite get the crowds that the Terracotta Army exhibition attracted; but it's still one worth queuing for.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments