Exposed: Voyeurism, Surveillance & the Camera, Tate Modern, London

A show at Tate Modern suggests that the supposed objectivity of the lens obscures a much nastier truth

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There are times, are there not, when you despair of Man? Learn how to split the atom and, a decade later, he will nuke Japan. Invent the internet and 80 per cent of its commerce will be porn. Think up the camera – the machine that never lies! Everyone their own artist! – and Man will instantly take photographs of people in pools of blood or leather masks.

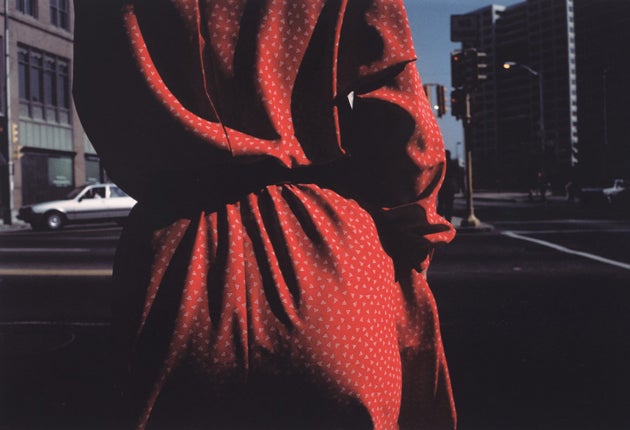

That, at least, is the inference of a show at Tate Modern called Exposed. Exposed does not set out to be a history of photography, but of that part of photography which has concerned itself with nastiness: ogling, peeping and lying. Choosing to dwell on these rather than on, say, flower pictures, might suggest a sordidness of mind on the part of the show’s curators, although the truth is that many photographs have been of unpleasant things. And this is particularly so of lens-based art, which is part of the business of Tate Modern.

Why should photography have attached itself so early to sin? The idea of the camera as incapable of untruth rests on a belief in its objectivity, which in turn implies a freedom from moral involvement. Put a mechanical box between you and the thing you’re looking at and you become immune. Were Henri Cartier-Bresson to have stared at the American Surrealist, Charles Henri Ford, as he did up his flies in a Parisian pissoir, Ford might well have taken it amiss. As it is, he appears unfazed by the exchange because Bresson is staring at him through a camera. (There was a flattering historical precedent, the aristophotographer Count Giuseppe Primoli having taken the same shot of Edgar Degas 40 years before.) Likewise with New York City, Robert Frank’s 1950s image of a legless man pushing himself on a trolley.

A notable thing about this last shot is that it suffers from the bane of Instamatic users, namely that it beheads its subject. Or at least it appears to. Frank was a professional street photographer: had he wanted to include the legless man’s head, he could have. Instead, he has sliced it off, either by composing the shot so as to do so or by cropping it later. The effect is of a picture snatched in a hurry, instantaneity standing as a metaphor for truth. And that instantaneity is, in all likelihood, a lie.

You can see why artists might have taken an interest in the moral issues bound up in this kind of image-making. A medium that claims to have a corner on visual honesty is always ripe for attack. One of the intriguing things about Exposed is that it makes no distinction between the mainstream photographic genres – news, fashion and street photography, the taking of smutty pictures – and lens-based art. Where one becomes the other on the Tate's walls is as difficult to pin down as where photography moves from objectivity to subjectivity or, if you prefer, from truth to lie.

Thus, in Room 5, the first umpteen works are by real-life celebrity snappers. There is Weegee's unkind shot, Marilyn Monroe arriving at a film premiere, and Doris Banbury's of Tallulah Bankhead and Eddie Fisher. On a facing wall are a pair of photographs by the English artist, Alison Jackson. One shows HM The Queen beaming as a liveried footman throws a football for a royal corgi, while the other catches Jack Nicholson beating a driver to death with a golf club. Jackson being best-known for her lookalike works, these are both fakes. But in what sense are they more so than the intervening image, Paris Hilton being taken back to Jail, by Nick Ut? This seems so patently staged – Miss Hilton's face a mask of flash-lit grief – that it is hard to believe that it wasn't staged. But it wasn't.

The show ends with rooms given over to images from, or purporting to be from, surveillance cameras, a genre lent topicality by Lib Dems' anti CCTV stance. The oldest of these – 10 shots of radical suffragettes from around 1913 – are surprisingly early, and oddly dismal. Along with our right to civic and sexual anonymity, they suggest, the camera has stolen our right to political privacy. I'm not saying Exposed is the cheeriest exhibition you will see this summer, but it will be among the most interesting. Like all Tate Modern shows, it is far too long, but that doesn't entirely hide its cleverness. Go if you can.

To 3 Oct (020-7887 8888)

Next Week:

Charles Darwent sees Newspeak at the Saatchi Gallery, the latest from the man who brought us Britart

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments