Charles Darwent on art: Chuck Close Prints - Process and Collaboration

Hundreds of tiny etchings create his vast portraits, but does knowing the process help us know Chuck Close? This fine show may fill in the gaps

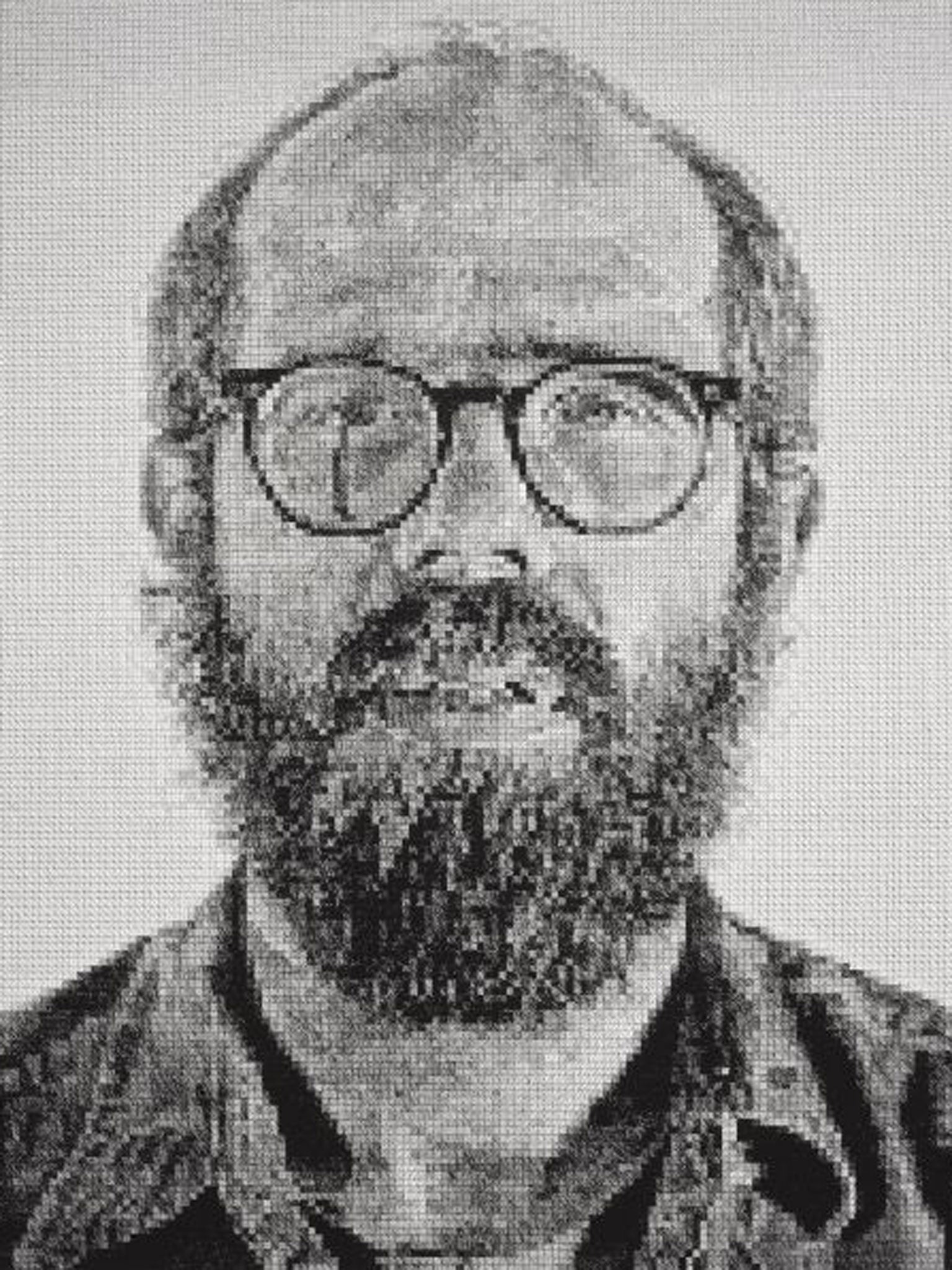

Notice the way the eyes follow you around the room. Well, the glasses at any rate, this being a portrait of Chuck Close. Bespectacled, bearded and rising 73, Close is no Mona Lisa. He may be like the man who painted her, though, unexpected as that may seem.

Close is known for great, big paintings of himself, made up of gridded diamond shapes framing bright, amoebae-like squiggles. Any individual diamond, isolated and blown up, could be an abstract work in its own right. Stand at the wrong distance, either too far or too near, and that is how they look. Hit the right optical biting point, and the squiggles coalesce into portraits, like the one on this wall at White Cube Bermondsey.

True, Self-Portrait (1977) is made up of squares rather than diamonds, and is a print rather than a painting. Still, Close's fascination remains the same. Each of the hundreds – thousands? – of the image's graph-paper squares has been gouged with an etching needle on a copper plate by the artist's own hand. For a print, Self-Portrait (1977) is vast, and so, commensurately, is the plate from which it came, hung on the wall alongside – 36 inches wide, the biggest single copper sheet commercially available at the time. That's an awful lot of gouging.

Close has picked out his own face by hatching every square more or less densely, so that the shading of each piece of the resultant mosaic is minutely different from the other. The process is hand-cramping, blinding and, I would think, unimaginably tedious. It is also fraught with risk. Once etched, a copper plate cannot be unetched. To know where the image was going to end up, Close would have had to know exactly how each square fitted into it. There are no second chances in copper, as he had found with the first of the so-called gargantuan prints, a 1972 mezzotint called Keith. Keith was test-proofed so thoroughly that its plate had worn smooth. There could be no dry runs for Self-Portrait (1977).

So why did Close choose to portray himself in this self-punishing way? There are several conventional answers to this question, all rather dry.

The first is that he was fascinated by something called "process", which means roughly that his prints set out to tell the story of their own making. Process art is not about the end result, but about the steps leading up to it: Self-Portrait (1977) is not the depiction of Chuck Close's beard and glasses, but of the way he etched them. It is, if you like, the opposite of a Jeff Koons balloon puppy, whose Valley-girl subject matter and shiny surface deny the huge complexity of its making.

Process art was certainly a big deal in the 1970s, being loosely allied to left-wing politics and an itch for visual honesty. Then again, the graph-paper substructure of Self-Portrait (1977) is that exotic creature, a Modernist grid. The critic Rosalind Krauss might sniff that no art had ever sprung from less fertile a ground than the grid, but, like contemporaries such as Sol LeWitt and Agnes Martin, Close remained wedded to it.

These desiccated answers are not what you feel as you wander around this museum-quality show, though. Yes, the Close who emerges from four decades of print-making, the lesser known part of his oeuvre, is more intellectual than you might have guessed from his paintings. But he is also more passionate. Hung on the gallery's walls are mezzotints, aquatints, seven-step linocuts, Jacquard tapestries, woodcuts, relief prints, an anamorphic self-portrait and another silk-screened in 111 – 111! – colours. You don't make art this obsessive just to prove a point.

No, to get close to Close, you need to step away from him, around the corner to a series of works called Roy. These, in an array of sizes and media, are portraits of his friend, Roy Lichtenstein. I wrote a couple of weeks ago about the moral anxiety of Lichtenstein's Ben-Day dots, and Close's travels through the history of print-making set off from a similar place.

From Leonardo on, art had been about revelation, portraiture allowing us to look into people's souls. In this fine exhibition's three big rooms, we see Close using every strategy of representation known to man only to end up by representing nothing, least of all himself. This isn't the glib nihilism of a Postmodern artist, but the horror of an instinctive traditionalist who has looked and looked and, at last, seen nothing but the reflection of his own glasses. Come to think of it, Self-Portrait (1977) may be like Mona Lisa after all, in that it gives nothing away about its subject. But then, neither image was meant to.

To 21 April (020-7930 5373)

Critic's Choice

Pop goes the Tate: a major Roy Lichtenstein exhibition is a crowd-pleaser, so book in advance to enjoy the pop-artist's iconic works, from familiar comic-strip style pieces to lesser-known gems, at the Tate Modern (until 27 May). Another popular-but-worth-the-queue exhibition is the Hayward Gallery's Light Show, featuring works by 22 artists, including a stand-out installation by James Turrell. Everything is illuminated until 28 Apr.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks