Altermodern: Tate Triennial, Tate Britain, London

The latest critical theory may reduce you to tears, but the art it inspires is engaging and entertaining

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Extra! Extra! Postmodernism dead! Globalisation suspected! Mmm, well, maybe. It is Tate Triennial time again and – triennials happening along less often than biennials – headlines are called for. For this, Tate Britain's fourth, they come courtesy of Nicolas Bourriaud, co-founder of Paris's impenetrably au courant Palais de Tokyo and inventor of the term "relational aesthetics".

If I understand them correctly (and this is by no means certain), relational aesthetics scorn the idea that art exists within boundaries – gallery walls, say, or the visual realm – and hold that art is to be found more or less anywhere: in DJ-ing, or knitting, or delivering lectures. It is a belief that has taken firm hold at the Tate, where Bourriaud works. So news that he has come up with a whole new word for this year's Triennial – and that that word forms the show's title, even – was bound to cause a stir.

Altermodern. That's "alter", as in "alternative", and "modern", as in "modernism". And that means what, exactly? Well. "Altermodernism", according to Bourriaud, "can be defined as the moment when it became possible for us to produce something that made sense starting from an assumed heterochrony, that is, from a vision of human history as constituted of multiple temporalities".

It may be that you feel an urge to weep here, so let me explain, insofar as I am able. In the olden days of the late 20th century, history was seen as a chain of events occurring in sequence. Each culture had its own history, sealed off from other histories, just as each historical event was separated from other events.

Globalisation hasn't merely swept away cultural differences, it has taught us to think of history differently. Just as geographical boundaries no longer count, so neither do historical ones: history, today, is an amorphous thing, a continuously recurring now. Postmodernism, by playing around with bits of old history, made itself part of that history. Now Postmodernism is dead, dispatched by Altermodernism. Or something like that.

Whether or not this is true, I will leave you to ponder. For the purposes of the Tate Triennial, what matters is that artists believe it to be true. Actually, that too is debatable. Go to the Saatchi Gallery's excellent show, Unveiled, and you will see contemporary art that is neither Altermodern nor Postmodern, but modern. This kind of art worries less about critical theory than it does about boring things like putting paint on canvas. Little of it is to be found at Tate Modern, and even less in the Fourth Tate Triennial.

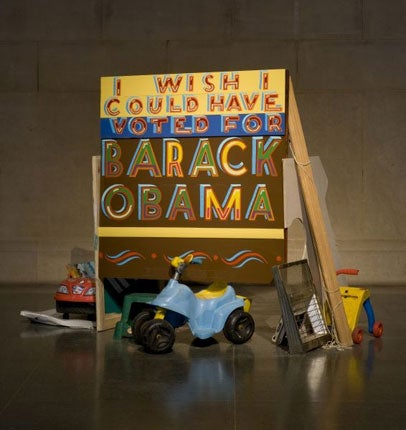

So what is Altermodern art? From Bourriaud's show, it is more or less what you'd expect it to be, which is work that sets out, in various ways, to be boundary-less. In the case of Rachel Harrison, this includes the simple boundaries of the art-object. What looks like an installation piece in one sub-room turns out to be three separate works – Second Voyage, Bike Week At Daytona, and A Whole New Game – including digital inkjet prints, a DVD player and a polystyrene lump with a nest of ping-pong balls in it. Then again, the three pieces may equally well be read as one piece: very Altermodern.

Travel also plays a big part in Altermodernity. Mike Nelson's Projection Room is carefully structured to exist nowhere, quite. The mid-Atlantic tones of its recorded voice could come from anywhere in the globalised world; the business of the titular booth actually takes place elsewhere, namely on the wall where its image is projected. (There is a lot of projection in Altermodern.)

Nathaniel Mellors's Giantbum requires the visitor to do his own travelling, through an odorous felt maze that doubles as a giant's innards to a mini-Cerberus of singing animatronic heads.

And then there is travel in the sense of change. Another tic of pre-Altermodern art was its lumpish tendency to stay the same. Bob & Roberta Smith's Off Voice Fly Tip will be replaced by a new version each Friday; Ruth Ewan's giant Squeezebox Jukebox plays a different revolutionary air every day at 2pm.

This is all massively engaging, and some of the work in this show is extraordinarily good: Subodh Gupta's giant mushroom cloud of pots and pans, Line of Control, is worth the trip alone. But Altermodern is also hugely selective in the art it showcases, in the history it writes. For a theory that spurns boundaries, Bourriaud's seems strangely boundaried. But it is also, heterochronies apart, a lot of fun.

Tate Britain, London SW1 (020-7887 8888) to 26 April

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments