Turner Prize 2018: 10 memorable winners of the controversial contemporary art award

From Damien Hirst embalming cattle to Grayson Perry's explicit vases, the accolade has continued to spark fierce debate since its inception in 1985

The winner of the Turner Prize 2018 will be announced tonight, with four emerging artists competing for the honour and the accompanying £25,000 windfall.

Forensic Architecture, Naeem Mohaiemen, Charlotte Prodger and Luke Willis Thompson are this year’s entrants, all video-centric creators concerned with “the most pressing political and humanitarian issues of the day”, according to Tate Britain director Alex Farquharson.

Response to the nominations has mellowed considerably in recent years but in its 1990s heyday, when the accolade was regarded as a key event in the “Cool Britannia” calendar and provided a reliable source of controversy.

The Turner was routinely picketed by the Stuckists, a protest group calling for a return to figurative painting, who would demonstrate outside Tate Britain dressed as clowns bearing placards dismissing it as “a state-funded advertising agency for Charles Saatchi” and arguing that it should be renamed “the Duchamp Award for the destruction of artistic integrity”.

“The only artist who wouldn’t be in danger of winning the Turner Prize is [JMW] Turner”, they would rather pointedly argue.

The Guardian was moved to question whether Fiona Banner’s 2002 entry Arsewoman in Wonderland amounted to art or pornography, putting the question to adult film star Ben Dover (”Porn is the new rock and roll and what this piece of art is, in my opinion, is verbal justification for it. It allows all the Islingtonites to get off on the sexy stuff without sanctioning porn”).

Culture Minister Kim Howells dismissed the prize as “conceptual b******t”, to the glee of Prince Charles, that same year.

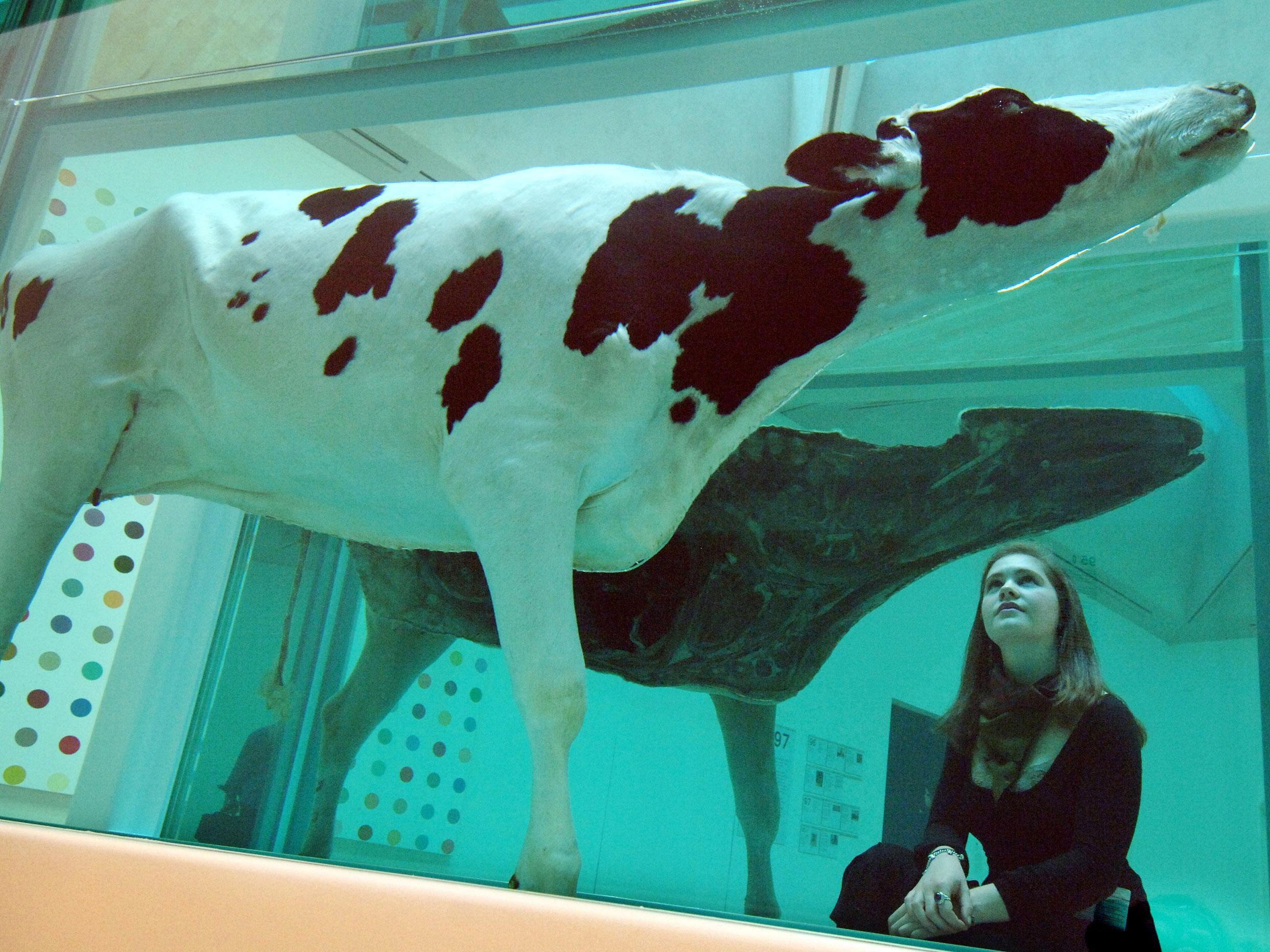

Damien Hirst’s cows preserved in formaldehyde are undoubtedly among the most iconic and divisive spectacles to have featured, along with Tracey Emin’s My Bed (1998), which didn’t actually win but was sufficiently notorious to inspire performance artists Yuan Chai and Jian Jun Xi to offer a riposte, staging a pillow fight among its sheets before being removed by security.

Both were synonymous with the so-called Young British Artists movement and came to be closely associated with the cigarettes-and-Chablis spirit of the moment.

The Turner Prize may be maligned in some quarters as pretentious or willfully oblique but, like Trafalgar Square’s Fourth Plinth, it provides a rare opportunity to put challenging, immersive contemporary art before the general public and for that service alone deserves to be cut some slack.

With that in mind, here's a brief look back at some of its many memorable winners.

Gilbert & George, 1986

The duo - famed for dressing alike and resembling cohabiting bank managers – won for one of their trademark stained glass-inspired psychedelic collages in the second year of the Turner’s life (painter Howard Hodgkin won the first).

They distanced themselves from the honour, however: “We don’t like prizes. We are apart from all that.”

Rachel Whiteread, 1993

Whiteread became the Turner’s first female winner for House, a sculpture made by using a derelict house in east London as a mould, filling it with liquid concrete and stripping away the exterior cast to create a “fossil”.

The divisive nature of the accolade was emphasised when she also won that year’s Anti-Turner Prize, naming her “the worst artist in Britain”, and saw her project dismissed as “meritless gigantism” by critic Brian Sewell, a staunch traditionalist who later argued that opening a gallery in the North East denied “more sophisticated” Londoners a chance to see new exhibitions.

Antony Gormley, 1994

Gormley, who felt so differently to Sewell he would later design the Angel of the North, won for Testing a World View.

The work was an installation of five identical cast iron figures, bent at the waist, arranged around the room in different positions to pose questions about architectural space and how human posture conveys mood.

Damien Hirst, 1995

Unquestionably one of the most famous works of art in the world, Hirst’s Mother and Child Divided presented four glass tanks housing a cow and her calf severed in half, the carcasses suspended in formaldehyde.

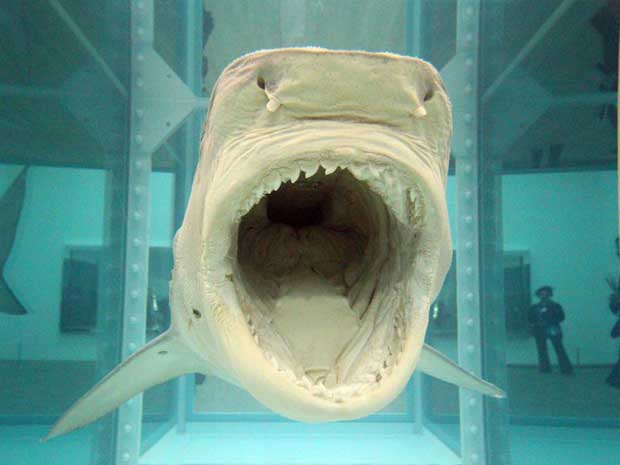

The work developed an idea Hirst first put forth in 1991 when he embalmed a tiger shark in The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living.

Punk rock Renaissance man Billy Childish, a former boyfriend of Tracey Emin and founding Stuckist, gave one of the most clear-eyed assessments of Hirst and his body of work in the song “Art or Arse? (You Be the Judge)”: “Damien Hirst’s got his fish in a tank/Some say it’s art, others think it’s w**k”.

Gillian Wearing, 1997

60 Minutes of Silence, Wearing’s film of actors standing still for an hour dressed as policemen, is perhaps best remembered as the subject of a live Channel 4 News discussion that Emin stormed out of while in a state of heightened refreshment, a defining controversy associated with the Turner.

Wearing unveiled Parliament Square’s first statue of a woman, suffragist Millicent Fawcett, at a ceremony in Westminster in late April this year.

Chris Ofili, 1998

When it comes to materials, Chris Ofili’s portrait paintings comprised of elephant dung coated in polyester resin take some beating. His reaction was also refreshing: “Oh man. Thank god! Where’s my cheque?”

One, No Woman No Cry, quoted Bob Marley and poignantly depicted a black woman weeping for the murder of teenager Stephen Lawrence in Eltham, south east London, a crime that shocked Britain in 1993 and saw the victim’s mother Doreen spearhead a campaign calling for an inquiry into the subsequent failed police investigation.

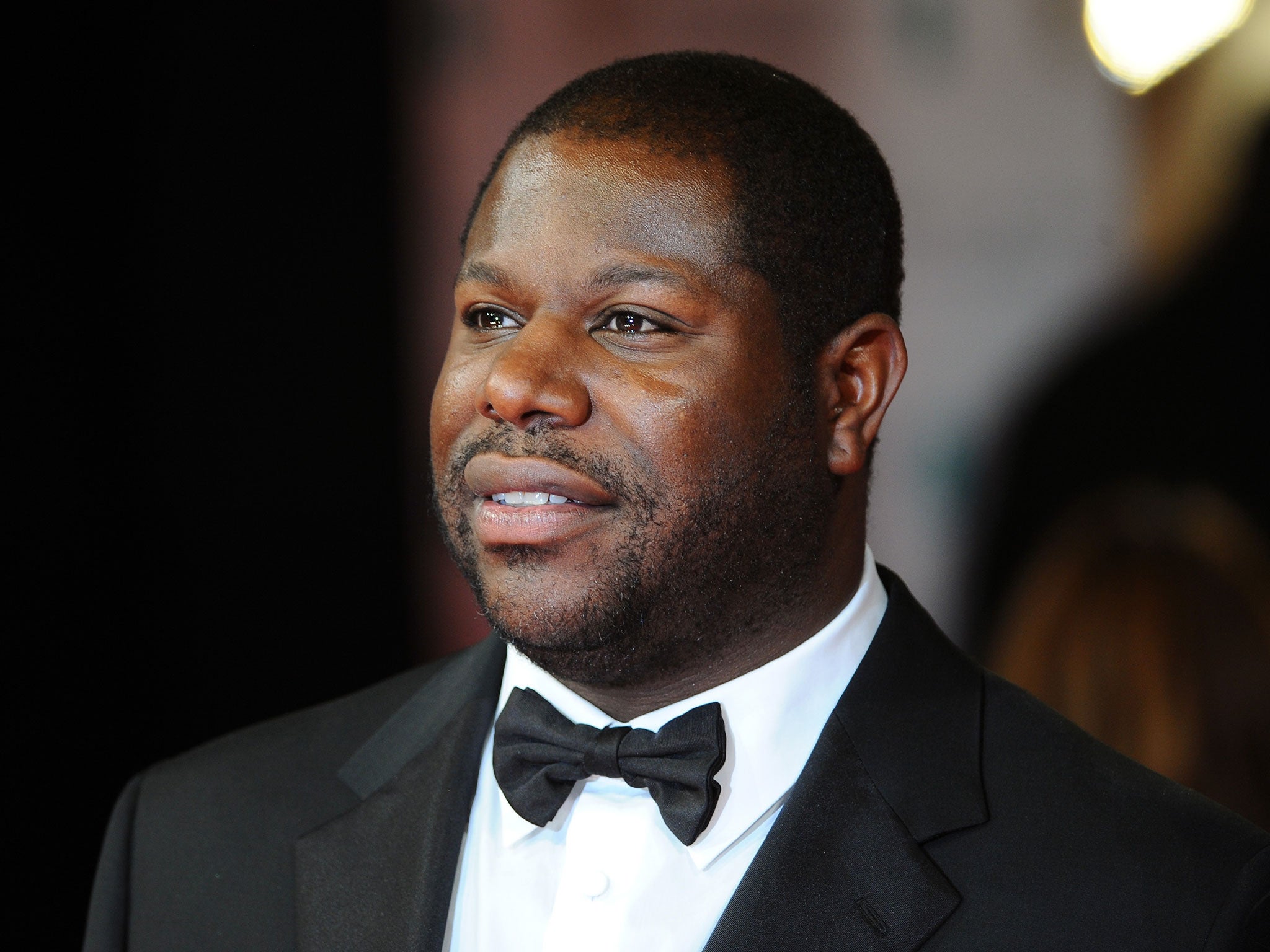

Steve McQueen, 1999

McQueen, who would go on to become an admired Hollywood director and make Hunger (2008), Shame (2011) and 12 Years a Slave (2013), was the first filmmaker to win the Turner.

Nominated for his 16mm black-and-white short films including Bear and Deadpan, in which he recreated a well-known Buster Keaton stunt from Steamboat Bill, Jr (1928), McQueen was somewhat overshadowed in the public imagination by Emin’s unmade bed.

Martin Creed, 2001

Work No. 227: The Lights Going On and Off did precisely what its title suggested, being an installation in which an empty room is intermittently plunged into darkness.

The piece confounded some and infuriated others, with fellow artist Jacqueline Crofton pelting it with eggs. Madonna added to the furore when she shouted “Right on, m********s!” live on TV, before the 9pm watershed, when announcing Martin Creed as winner.

Ben Dover liked it though.

Grayson Perry, 2003

Hailed as “the first transvestite potter to the win the Turner” (”That we know of”, he adds), Grayson Perry was honoured for his classically beautiful ceramic vases painted with satirical – and frequently sexual – contemporary imagery.

Accepting the award in the guise of “Claire” his teddy-sporting alter ego and wearing an exquisitely embroidered Victorian party frock, Mr Perry quickly became a national treasure.

Now primarily working in tapestry, he has since become a popular broadcaster, tackling themes related to social class and the changing face of masculinity on Channel 4.

He won huge plaudits for his 2013 BBC Reith Lectures “Playing to the Gallery”, as good an introduction to the often perplexing world of modern art as you could wish for.

Susan Philipsz, 2010

One of the most interesting recent winners was Scotland’s Susan Philipsz, the first to win for an entirely aural work.

A recording of the artist singing the traditional sea shanty “Lowlands Away” under Glasgow’s bridges was played through speakers into the exhibiting gallery, conjuring an evocative sense of place and the past calling us back through time with ancient words.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks