Grandees warn of self-censorship in the arts

Debate at Houses of Parliament sees panellists call for “counter-protests” in favour of freedom of speech.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Artistic institutions in Britain are increasingly self-censoring subversive material to secure funding and avoid protests, according to a panel of arts grandees.

Jude Kelly, artistic director of the Southbank Centre, Munira Mirza, deputy mayor for education and culture, and Shami Chakrabarti, director of human rights organisation Liberty were among those who called the rise of self-censorship “chilling” and “catastrophic” for British culture.

Ms Kelly, speaking at a debate at the House of Commons, the first on artistic freedom of expression, also called for “counter-protests” in favour of freedom of speech.

The debate came ahead of the elections in the UK and Belarus, and follows incidents in the UK where artists’ work was cancelled due to protests, as well as the recent murders of cartoonists in Paris.

But as well as attacks on freedom of speech from the outside, artistic institutions are censoring work before it even reaches the public, according to the experts.

Michael Attenborough, artistic director of the Almeida Theatre for over a decade, introduced the event, saying that even since leaving his post two years ago, “something is beginning to creep in [at arts organisations] that I can best describe as self-censorship”.

“There is an apprehension growing up around access to subsidy,” he said. “People are admitting privately that they are concerned they are self-censoring what they are doing. This is catastrophic.”

Mr Attenborough is a trustee of the Belarus Free Theatre, which presented the debate. The organisation was founded in response to the heavy artistic censorship from the country’s dictatorship. It performs underground in Belarus and the founders have been in exile in London since 2011.

“The conscience and the soul of the country consist within the artistic community of this country,” Mr Attenborough added. “Once we compromise that, we compromise something very serious.”

Ms Mirza said one worry was “self-censorship that comes from the shame of offending cultural orthodoxies... It’s harder to have that debate because it’s so emotional.”

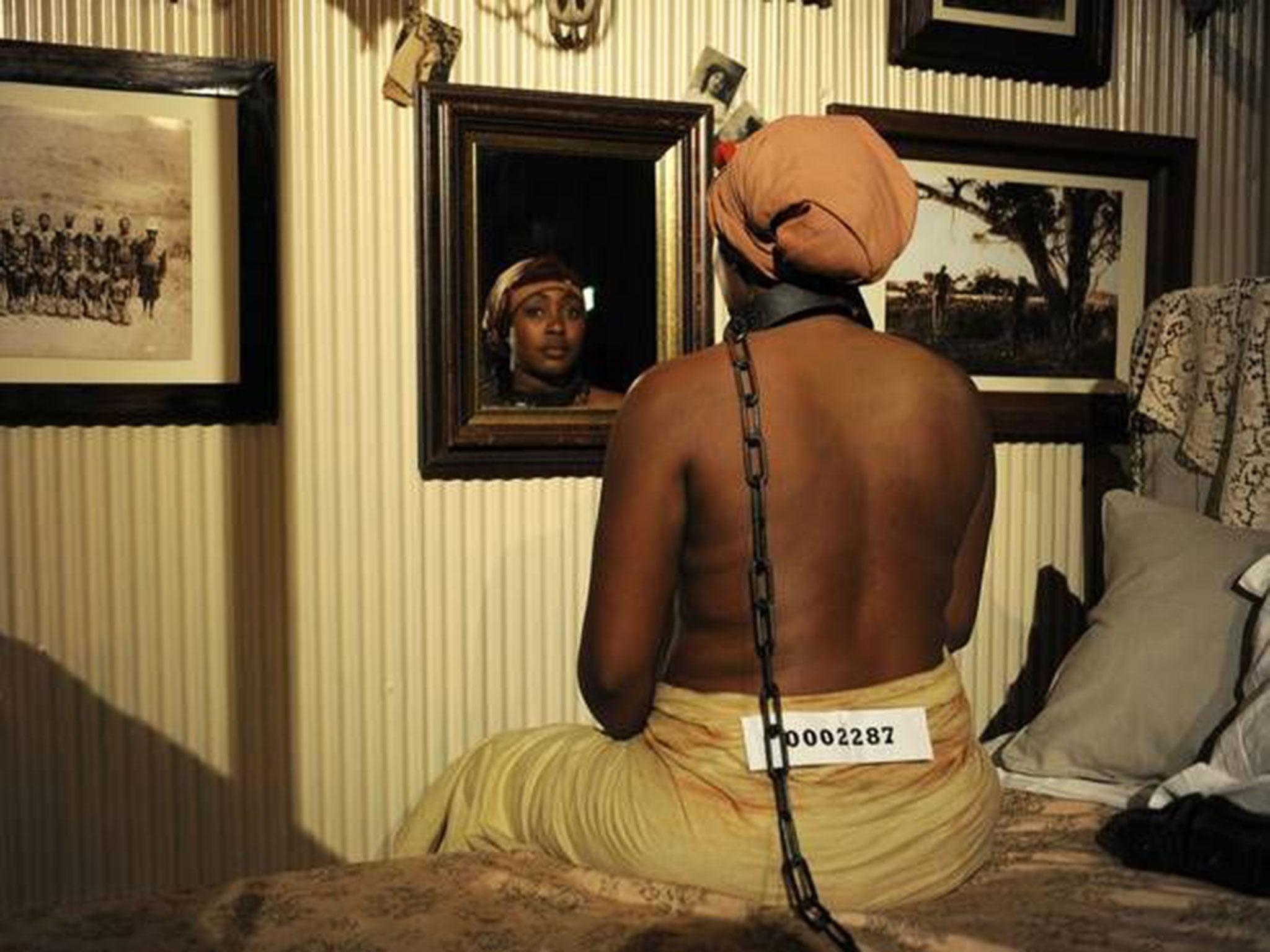

This follows the closure of controversial show Exhibit B in London last year, which the deputy mayor for education and culture said was the “wrong decision”.

In September the show, which used black actors in chains to recreate the 19th-century phenomenon of the “human zoo”, sparked protest from many who called it racist. It was cancelled due to safety fears, though the performers hit back, with one saying those involved had been denied artistic freedom of expression.

While some institutions are committed to putting on difficult work, many are hampered by their boards, Ms Kelly said.

“There are endless institutions and boards who feel institutionally anxious about politics, full stop,” she said. “The more a country at state level makes people feel subsidy requires you to be cautious about politics... that’s a dangerous starting point. I’ve seen it happen in this country.”

Ms Chakrabarti said that during her decade-long tenure at Liberty, one of the incidents she has “most regrets” about was when the play Behzti was shut down after sparking riots outside Birmingham Rep in 2004.

“No doubt there were understandable concerns, I’m not saying it was an easy decision, but it was a very bad signal,” she said, calling it a “particularly dark moment” in modern British cultural history.

Ms Kelly said the British should demonstrate they value artistic expression and should “counter-protest” shows that have been shut down in favour of freedom of speech. “It’s up to the arts to protect the notion of free speech.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments