In an era of minimalism, five families share the heirlooms they've restored

Services offering artefact maintenance and repair can help us keep items that hold precious memories intact

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Amid all the frenzied decluttering, organising and tidying going on these days, it’s easy to overlook the special things worth keeping. They may be locked in a safe-deposit box, wrapped in tissue in a wardrobe or entombed in a plastic container in a storage unit. They might be faded or torn, eaten by moths and the passage of time. Rescuing a family artefact takes thought and often money.

But the act of saving it and honouring it can be tremendously satisfying. Ingrid Fetell Lee, designer, author and founder of the blog the Aesthetics of Joy, believes in the power of ordinary things to create extraordinary happiness. “I think when you keep fewer things, you value them more,” she says. “Instead of having thousands of photos in boxes, you keep and frame the ones you really love.”

Lee says that when objects are invested with experiences, they can prompt a memory of an event or sensation. “Keeping those things closely around you matters, sort of like souvenirs from a vacation,” she says. “There is a sensory experience embedded in that object.”

There’s an ever-expanding number of ways to preserve those memories. Shana Novak of the Heirloomist created a business of photographing them, blowing up the images and turning them into artwork. Novak, who is based in New York, has photographed a beloved Millennium Falcon model, a tattered handwritten recipe book and a grandfather’s violin. “These treasures have the same love-from-the-gut feeling,” she says. “They are all special in their own way.”

We asked five families about the objects they could never part with, the heirlooms they’ve cherished and preserved. Here are their stories.

***

Patrick Gossett grew up in Riverdale Park, Maryland, where some of his fondest childhood memories were made in the family dining room. When his mother pulled her eight jewel-toned wine glasses out of the china cabinet, he knew something good was about to happen. “My mother loved beautiful things, simple things,” Gossett says. “These glasses were brought out for special occasions. They meant a lot to her, and they mean a lot to me.”

In the 1930s before she was married, Gossett’s mother, Elizabeth, took the streetcar downtown to her job as a secretary. The women she commuted with – Lib, Stell, Marie, Mable, Rhoda and Elaine – became her posse. The group regularly passed a fancy Connecticut Avenue shop where they often stopped and Elizabeth would admire a set of colourful hand-blown wine glasses.

When she married in 1935, the women pooled their money and gave her the glasses as a wedding present. They became a symbol of festive times in the Gossett home at holidays or “when the girls would come over for birthday dinners or showers”, says Gossett, whose father died when he was six. “They would have so much fun.”

Gossett inherited the glasses in 2000, when his mother died at age 88 and he and his two older brothers divided up her things. “You go back to those things in your life that bring back pleasant memories,” says Gossett, 65, now retired from the hotel and event-planning business. He uses them in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, where he and husband Howard Menaker do most of their entertaining, as their Logan Circle condo is small.

“I know decluttering is the new emphasis these days,” Gossett says. “But knowing how much my mother loved and used these makes our own occasions even more significant.” The glasses were all in good condition and had always been hand-washed. But last year, the stem of the green one snapped off.

Knowing how much my mother loved and used these makes our own occasions even more significant

“For a while, I just left it,” Gossett says, but he decided it was important to keep the full set. He had dealt with conservation professionals as president of the Riversdale Historical Society, so he asked conservator Anne Kingery-Schwartz to fix the break.

Kingery-Schwartz cleaned and degreased the glass, aligned the break edges and applied epoxy to the break. A chip of the original glass was missing, so epoxy was used to fill in that area. She constructed a support to align the edges and hold them firmly in place. It took about eight weeks. “You can’t even tell it has been repaired,” Gossett says.

The set returned to Gossett and Menaker’s Thanksgiving table. “In life, you hold on to the good memories. These were full of them,” he says. “You can’t put a price on that kind of joy.”

***

The diamond cocktail ring that Marcia Kepler Noor’s mother gave her in the 1980s was gorgeous, but it seemed a bit glitzy for everyday wear. The cluster of diamonds on high prongs formed a flower, a design popular about 100 years ago. The ring was a family heirloom and had originally belonged to Kepler Noor’s great-grandmother, handed down for generations.

Kepler Noor, 53, kept the ring hidden away most of the time. But after she gave birth to twin girls, Zoe and Alex Noor, in 2002, she says, she gained “a different perspective on passing things down and saving memories”. Kepler Noor’s mother, Esther Kepler, had died before Zoe and Alex were born, but the family speaks of her often, has photos of her around the house and uses her recipes.

Zoe remembers admiring the ring from time to time. “When we were younger we loved looking at my mum’s jewellery,” she says. “She always talked about this ring, but she almost never wore it.”

As the girls approached their 16th birthday last year, Kepler Noor and her husband, Enam Noor, owners of Insightin Health, a Baltimore health analytics firm, decided that repurposing the ring into a gift for each girl would be a wonderful way to honour the past and embrace the future.

She found Alexandria & Co Workshop and Design Studio online. Owners Tim Shaheen and Meaghan Foran had taken over an established Alexandria silversmith and jewellery business and added a focus on custom designs. Kepler Noor, who lives in Eldersburg, Maryland, told Foran and Shaheen she didn’t want anything showy. “The girls are into sports; they play soccer,” she says. “They aren’t into large rings.”

Foran and Shaheen designed each twin’s ring to be slightly different. Both got a new sapphire (yellow for Zoe and blue for Alex) and four small diamonds from their grandmother’s ring. Zoe’s is set in 14-carat gold, Alex’s in 14-carat white gold. The centre diamond was set into a circle necklace on a rose-gold chain for Kepler Noor and is flanked by two new small diamonds that represent her and her sister, Rachel.

The girls were presented with the rings at their 16th birthday party at a restaurant in December. Their mum gave a speech about how proud she was of them. Even the server cried. “I love the rings because we made them almost the same, but different, just like they are,” Kepler Noor says.

That ring was like a piece of my mum. But the great part is that now, we can all wear it

Zoe and Alex were thrilled. “I never owned anything with a story like this,” Alex says. “When I got the ring, I knew I would wear it all the time.” Says Kepler Noor: “That ring was like a piece of my mom. But the great part is that now, we can all wear it.”

***

The small mahogany captain’s desk in Bryant and Madeleine Mitchell’s Old Town Alexandria, Virginia townhouse has lots of stories to tell.

The 1870 English antique has been in Bryant Mitchell’s family for more than 100 years. He first remembers the piece, called a Davenport desk, at his grandfather’s house in his hometown of Hampton, Virginia. “My grandfather Solomon Phillips was my best buddy. We were very close,” says Mitchell, 72, who has a commercial real estate firm in Alexandria. “This desk means a lot to me.”

Mitchell’s mother told him stories of when her three older sisters would receive gentlemen callers in the living room. All of a sudden, their father would come down to the desk to “pay bills”. “If Grandpa saw they were staying too late, he would come into the living room and act like he was writing at this desk,” Mitchell says. “The guys would get the hint and wrap up their visit.”

No one knows exactly when the tilt-front desk came into their family. The top lifts up, and there are individual slots for letters. It has unusual small drawers on the side that used to hold rolls of nickels, which were given out to Mitchell’s mother, her sisters and her brother for lunch money. (“Yes, school lunches cost five cents back then,” Mitchell says.) There are also stories that a family of mice had once lived in it and had chewed on a piece now missing from one of the tiny drawers.

Bryant and Madeleine inherited the desk in 2006 from his Aunt Agnes. She had insisted on giving it a bit of TLC before it passed to the next generation, so the inheritance included paying for it to be polished up and having loose parts reglued by Cavalier Antiques in Alexandria.

The desk was ready for its new home with the Mitchells and their daughter, Phillips. The family joked that “Bryant might do the same thing with this desk”, says Madeleine, a gallery director at Doris Leslie Blau, recalling Solomon Phillips’s “bill paying”.

Of course, he never did, and now Phillips, 28, lives in New York. The plan is that someday, she’ll start a new chapter in the history of the desk.

***

When Nathan Canestaro was growing up, he didn’t know much about his grandfather Herbert Todd’s service in the Navy in the Second World War.

“He never talked about the war,” says Canestaro, 45. “He put that phase of his life behind him. His war memorabilia was hidden in a box in the basement. When I asked him about it near the end of his life, he started crying. It broke my heart.”

Todd, a master carpenter in Cortland, New York, died in 2010 at age 89. That’s when Canestaro, a defence analyst for the federal government, started unravelling the story of Todd’s service in the Pacific. He had been a tail gunner on an Avenger torpedo bomber on the USS Cowpens, a light aircraft carrier nicknamed the Mighty Moo, from 1944 to 1945.

“I wanted to find out more,” says Canestaro, who lives in Washington, DC with his wife, Sarah, and two young sons. “I’m interested in military history, and I didn’t want my grandfather’s things to just be another box of stuff. If you don’t pass these stories on, they get lost.”

I didn’t want my grandfather’s things to just be another box of stuff. If you don’t pass these stories on, they get lost

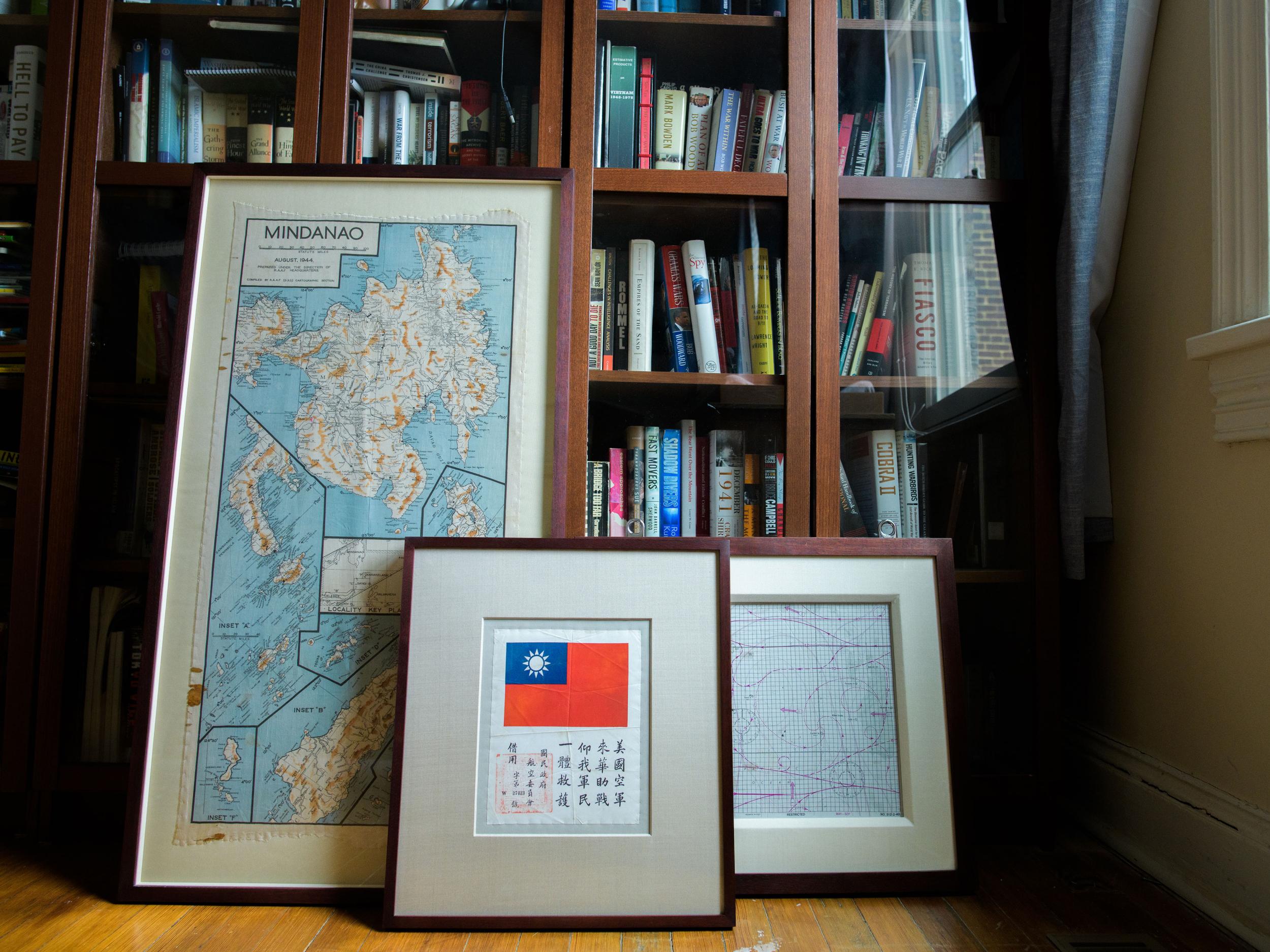

The box eventually made its way to Canestaro. Included in it were two uniforms, a flak helmet, service ribbons and photos. The most intriguing find: a plastic bag full of colourful fabric maps and documents folded in tiny squares.

This year, he restored four of the cloths. One was a rayon “blood chit”, which aircrews were routinely issued containing a message in a local language that asks for help if stranded and offers rewards. (The term “blood chit” means that it was meant to save a life – that the US government promised to pay for the life of the bearer.) The others were survival maps, navigational aids for downed aviators: two double-sided rayon maps of Pacific Ocean currents and a large silk map of Mindanao, Philippines.

Canestaro took the heavily creased and stained materials to conservator Julia Brennan of Washington’s Caring for Textiles. Brennan gently cleaned the pieces and dried them on sheets of glass. Then the blood chit was mounted on an archival padded board; the maps were carefully stitched to silk organza borders for framing. The next step was taking them to Bill Butler of Archival Art Services in Alexandria, Virginia. Butler put them in custom walnut frames using silk-wrapped mats and UV-filtering plexiglass. The two double-sided survival maps were placed in double-sided frames.

What would Todd have thought of his grandson putting so much effort into restoring, framing and displaying his war memorabilia?

“Honestly, I think Grandpa would have been appalled,” Canestaro says. “It was not in his nature to draw attention to himself. But I want to pass these things along to my kids, and I will only do it once.”

“When someone asks, ‘What is something worth to you?’” Canestaro says, “this is worth a lot.”

***

These days, formal china isn’t often in great demand when family heirlooms are divvied up. But for Deb Baum and her sister, Becca Groothuis, figuring out who is going to get their mum’s gold-rimmed vintage Lenox is a continuing negotiation.

“We joke about it and call it ‘the embattled china’,” says Baum, who admits they’ve been bantering about it since they were children setting the table. For now, the two of them just agree to disagree about the 12 dinner plates and 12 salad plates in a Lenox pattern with a raised fruit motif. And no, they don’t want to divide them in half.

“Growing up in Omaha, we always knew my mum was a wonderful hostess, and the china she used for Thanksgiving dinners and Passover Seders was her most special,” says Baum, 43, who now lives in Baltimore with husband Matt and two children.

Nobody recalls whether the set was a wedding gift for Donald and Ann Goldstein’s 1970 nuptials or had belonged to another family member. (We sent a photo of the plate front and back to Lenox, and a spokeswoman confirmed that the plate seems to be a rare combination of the Autumn and Westchester patterns and was made between 1918 and 1930.)

Ann Goldstein died in 2011. Now her husband has moved to a condo, and the china is in storage. “Neither of us can let go of it, so it will stay with my dad for now,” Baum says.

But Baum found a way for both sisters to enjoy the china in the meantime. In 2015, Novak, a childhood friend, started her Heirloomist business. She has photographed heirlooms of every dimension, from matchbooks and gold pocket watches to wedding dresses and Ellis Island trunks. One woman had her make a six-foot-tall print of a Happy Meal box that once contained an engagement ring and a proposal of marriage.

A dinner plate was shipped to Novak. The photograph she took makes the plate look larger than life. It is displayed in a white wood 42-inch-square frame and hangs on a navy blue wall in the Baums’ dining room. Baum commissioned a smaller version as a gift for her sister, who lives in Chicago.

“It’s the perfect way to have the china in my home and be reminded of my mum and the rest of the family memories that went along with it,” Baum says. “I like to find meaning in the things that I look at every day.”

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments