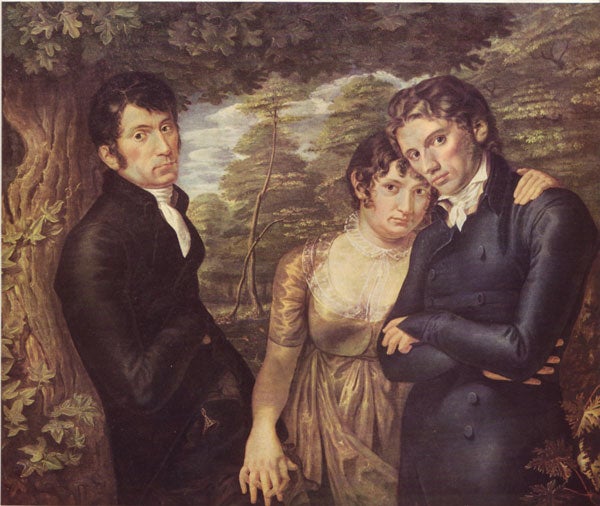

Great Works: We Three (Wir Drei) (1804-05), Philipp Otto Runge

DESTROYED, formerly Hamburger Kunsthalle

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It's an odd but obvious fact, that all self-portraits are self-portraits of artists. There are portraits of many kinds of people, but the special me-on-me perspective that self-portraiture offers is restricted to that small class of people who can paint.

Anybody (practically) can write their autobiography. Not anybody can paint their own picture. We all – if we have eyes – look in the mirror, and we may have self-knowledge coming out of our ears, and a powerful urge to show the world. It's not enough.

But there's a way round this problem. Call it: the imaginary self-portrait. It takes a proper artist to do it, but the subject is not the artist. Through an act of creative impersonation, the artist depicts some other person as if they had depicted themselves – and we see this non-artist's face gazing out and marked (say) by an intense inner drama or some other telltale sign of self-portraiture. That's one way of doing it, at least.

Philipp Otto Runge's We Three is a group portrait. Specifically, it's a "friendship picture", a common genre in the Romantic age, usually showing two young men, where one of them, often, is the artist himself. We Three is like that. It's a group portrait of intimates, and it includes a self-portrait. It shows the artist, and his wife Pauline, and his brother Daniel.

If you knew there was a self-portrait in the group, but didn't know who, who would you say? Surely the man on the left, lying back against the tree – moody, droopy, lean and slightly ill, he looks like the solitary, sensitive type. But, strangely, it is not him. It's the other man who's the artist, the man who holds a more public, less poetic stance. This figure is the self-portrait, the I, in the group.

But look again, and something even stranger appears. We Three has more than one self-portrait in it. The painting's title is a prompt – it's a kind of invisible speech bubble. And it's like that device, traditionally used to indicate a self-portrait, where the figure points to itself, as if to say: this is me. In this picture, the title does that job. The figures are saying: this is us.

You almost don't need the title. The figures themselves seem to speak to us in the first-person plural. All three might be self-portraits, one real, two imaginary – or rather, not three separate self-portraits, but a group self-portrait. Literally, Runge painted it, but it's not a portrait of me, the artist, and of her and him, my wife and my brother (or even three me's). This is a portrait of us, Philipp, Pauline, Daniel.

Their looks unite them. They fix you steadily and equally with their gazes. These gazes have the piercing interiority of self-portraiture. But, all turned on you, they are also what bind the three figures protectively together – just as when you walk into a room of people, and they all turn towards you, and their collective stare makes them a group.

Their bodies complicate this togetherness. Three's company? There's an unfathomable intimacy between them. Look at the way they lean. They're a one and a two. Pauline leans faithfully her head against Philipp's, and his leans his against her. Daniel, meanwhile, leans away.

But then look at their hands. Pauline's hand left clasps Philipp's shoulder, closing their marital embrace. His folded arms don't reciprocate. Her right hand links fingers with Daniel. From her head-to-head to her hand-in-hand, she is the axis of the group.

Those linked fingers you could almost miss, though. Daniel's hand arrives from nowhere. He seems not to notice. The contact looks surreptitious, and dangerously near to his privates. What's going on?

Perhaps a woman has come between two brothers (through marriage), tries to bring them together (by loving both), and comes between them again (through adultery)? It's a subject for drama, not usually for group portraiture. It's only a hint. But in the gazes of the three you can also read secrets.

This is what makes We Three a good example of that impossible genre, the group self-portrait. In the relationship between its three figures, you have the same sense of hidden depths that is characteristically found in the mono self-portrait, in the relationship between the artist and him/herself – and as in a mono self-portrait, so here, these depths are transmitted by faces turned to the viewer, faces that both reveal and conceal the heart's plots. We Three: you'll never know.

The picture itself you'll never know either, not directly. Formerly in the Hamburg Kunsthalle, it was destroyed by fire while on exhibition at the Munich Glaspalast in 1931. Fortunately, a colour photo has survived.

About the artist

Philipp Otto Runge (1777-1810) was the most original of the German Romantic painters. He is best known for his portraits of children, terrifying little giants, bursting with chunky vitality. But in his short life he initiated a number of artistic projects that took off in the later 19th and 20th centuries. He explored the growing forms of plants (in semi-abstract silhouettes) and the physics and symbolism of colours (devising the colour-sphere). In 'Times of Day', he envisaged the "total work of art". Of its sequence of four pictures, only 'Morning' came near completion before his death. But he had planned a dense, allegorical mystical-Christian scheme, which would be shown in a special building, a visual-verbal-musical-installation-experience. It's a dream that has inspired – in different ways – artists from Richard Wagner to Mark Rothko and still hasn't quite lost its shine.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments