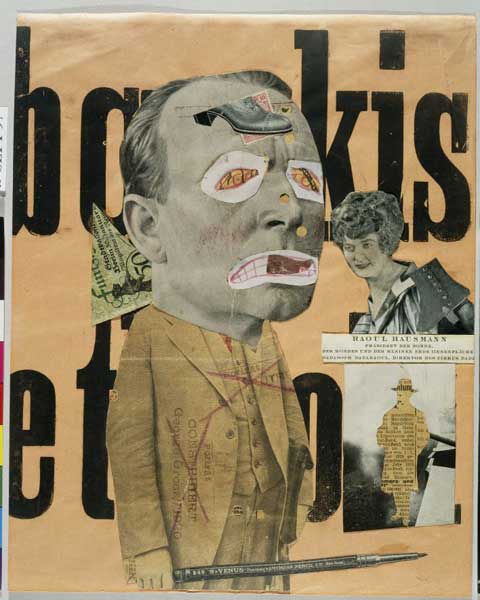

Great Works: The Art Critic 1919-20 (31.8x25.4 cms), Raoul Hausmann

Tate, London

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Crude and a little vicious, you might say. And yet do we not agree, at least in part, that is there something wholly preposterous about the idea of the art critic? He judges that which he almost certainly cannot make. He imposes arbitrary rules at the drop of a hat in the full knowledge (held in private, of course) that the anarchic world of art-making is hopelessly mired in subjectivity. He creates categories that suggest that art has a coherent story of sorts – or perhaps, at best, several loosely interlinked stories – when we all know in our heart of hearts that art (like life and history) consists of one damned thing after another. He is immensely superior to that which he judges, and we see that in the flourish of his dress and his generally sombre and often rancorous demeanour. He usually writes too quickly when the slowness of rumination seems to be demanded of him. He pretends to think for himself when we are keenly aware that he is heavily influenced by the fashionable opinions of others, and especially by those who possess the money and the recognition that he so desperately craves. In fact, he seems fashioned in order to be a perfect object of ridicule for the Dadaists, and that is precisely what has happened here in this collage by the painter Raoul Hausmann, which was made in 1919, part way through the tumultuous Dada heyday, which burst forth in Zurich 1916, and continued to flourish through the Weimar years (when millions of marks were worth as much as a few bits of loose change), and on into the ever more laughably unpredictable future.

The photo-collage, being flimsy and trashy and makeweight in appearance, is a perfect form to choose for an art critic, equipped as he so often is with glittery bits and pieces of superficial learning garnered from here and there, which are assembled, at critical junctures (press time) into semi-coherent arguments, and often begin with a hugely self-conscious and self-referential roar, and gradually sputter along to a less edifying conclusion. Here, as in the mind of the critic himself, bits and pieces appear to be floating about almost at whim. Fragmentary scraps of typography of various sizes – vertical, horizontal, on the tilt – snarl and mew at us. A well-polished shoe is doing violence to the 10-pfennig stamp that adorns the critic's forehead. The name of the painter and satirist George Grosz appears to be rubber-stamped, side-on, across the critic's jacket as if he is a bit of random merchandise, but this piece of identification is crossed out. So we are momentarily invited to contemplate what immediately proves to be a red herring.

And here, amid all this boisterous satirical mayhem, the fellow proudly stands, art's subject and art's object of undying mockery simultaneously, staunch in his heavy, double-breasted suit, receding hair well combed, wielding his giant critical instrument, whose lead seems to be fully extended in readiness for the next fierce critical skirmish. He has a large and ungainly paper mouth imposed upon his mouth – which means that we know that what he is about to say (and he will be saying it far too loudly because this mouth will not be allowing him to whisper his opinions) is not entirely of his own devising. The triangular fragment of a green, 50-mark German bank note – the Berlin bear rears rampant on its feet – seems to be projecting from his upper back, stabbing into him. It also looks a little like the key that will wind him up and enable him to walk in one direction or another. The handy key of financial influence perhaps. The upper segment of a fashionable, perfectly coiffed society lady floats towards him, and beneath her is displayed Hausmann's own visiting card, which declares him to be "President of the Sun, the Moon and the Little Earth (inner surface)."

It is a work of mad, irreverent clowning. It tears into the notion that art is a repository of eternal values. It seems to say: the whole damned art world, as represented by this self-important, preposterous, puffed-up bourgeois gentleman, stinks to high heaven. And what better choice of background colour than this queasy peach?

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Raoul Hausmann (1886-1971) was a founding member of Club Dada in Berlin. He wrote books and essays in support of the movement, and co-organised many of its events and soirées. In 1927, he tried to patent a device called the "Optophone", which was intended to convert light into sound.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

5Comments