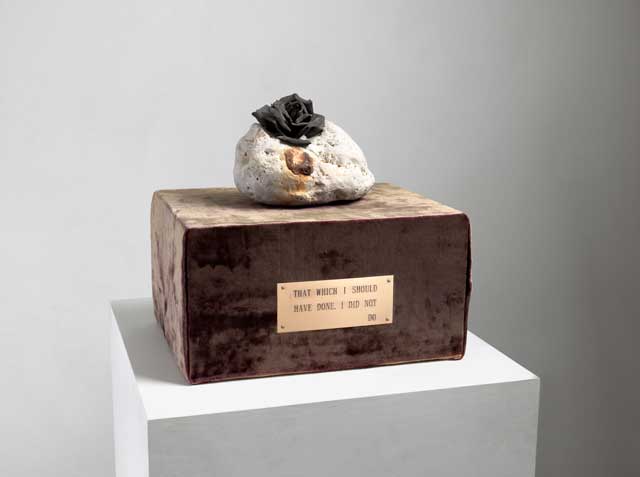

Great Works: That Which I Should Have Done, I Did not Do, 1998 (36cm by 37cm by 27.5cm), Cy Twombly

Private collection

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Cy Twombly, who died this week at the age of 83, is better known for his painting than his sculptures. Indeed he is hardly known for his sculptures at all. Squiggly lines across the canvas, with words, extracts of poetry and the paint smeared on by finger, that is what he is known and admired for. And yet he pursued sculpture through most of his working life. And it shows, even more than his two-dimensional work, the wit, the literary references and the sense of the past which made him such a creative and evolving artist.

That Which I Should Have Done, I Did Not Do, from 1998 and now on display for the first time ever at the Dulwich Picture Gallery exhibition of his work set against that of his hero, Nicolas Poussin, is a case in point. It's a work combining many materials – velvet, wood, stone, bronze, brass and metal screws – and even more allusions. The base is a wood box covered in faded purple velvet. It supports a stained stone on which is placed a bronze rose. On the base is the legend that gives the piece its title.

The overall intention, not least the memorial plaque but also the use of bronze and supporting base, is clearly to mimic the sense of the memorial. And in that sense the piece can be interpreted precisely as that. The rose is the symbol of beauty that fades but it is metamorphosed into permanence by its transfiguration into bronze, just as in the memorial casts of the dead in previous centuries. The stone is the basic material of the mausoleum, but it is also given life by the stain and corrupting smear upon it. A man who chose to live in Italy for most of his life and knew intimately their classical remains and funeral art, Twombly also liked to subvert it by place the sepulchral against the mundane.

The legend could refer to the artist himself, the work an illustration of just how short he felt he had fallen in trying to achieve the art he wanted. It is actually taken from an Ivan Albright painting in the Art Institute of Chicago, which Twombly knew. But it also contains a nod, and a riposte, to Poussin's most famous dictum: "Je n'ai rien négligé" ("I have neglected nothing."). Poussin was the artist of the precisely prepared, the perfect detail. Twombly was a creator of the spontaneous, the smudged, the questions left open.

You can over-interpret works such as these. It may be interesting to know that the bronze rose is cast from a plastic rose, a form he used in a number of his sculptures, but it doesn't necessarily aid your appreciation. Yet in Twombly's case, there is a deliberate playing with audience expectation and an intentional ambiguity of meaning, which owes something to his early enthusiasm for the art of Paul Klee but also an influence of surrealism. Twombly is usually cast as an abstract artist, a friend of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. In reality, although close friends with these and other artists of the New York Abstract School, he deliberately diverged from their ambitions of pure abstraction in colour to introduce drawing, words and different materials. He practiced free-hand drawing at night when he could not see where the line was going. He sat on the shoulders of an assistant so that he could draw continuous lines across huge canvases.

His ambition was huge. He wanted to gather in past and present, literature and painting, classicism and unconscious creation all together. But he sought to do so by making his works, even the largest, deliberately unmonumental: by playing with the line, by undercutting the force of the paint with the delicacy of pencil and confusing the abstract with words from his favourite poems. Always he sought to give his works a sense of the fragile, the indeterminate and the unresolved – in other words, what makes us human.

He kept this particular work in his studio for over a dozen years. Whether he intended it as his epitaph, it does describe his life – both an artistic career worked against the grain of his times and a cheerful admission of the gap between human endeavour and its fulfilment.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Edwin Parker "Cy" Twombly, 1928-2011, was one of the outstanding figures of American post-war art, famous for introducing pencil drawing, words and literary references into abstract art and for painting vast canvases. A devotee of classical art and literature, he spent most of his life in Italy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments