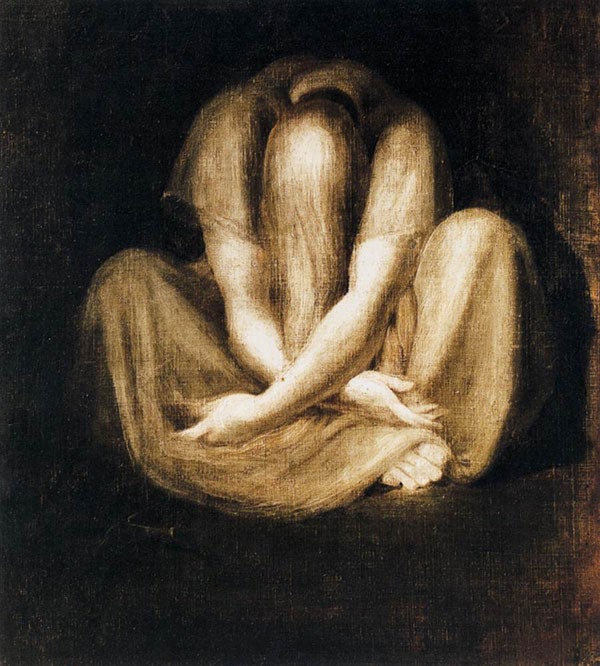

Great Works: Silence (1799-1801), Henry Fuseli

Kunsthaus, Zurich

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The psychology of shapes is good business. Find out your shape-personality type and you'll know yourself, both well and profitably. The square? Your colleagues will come to you for help. The circle? People will bring you their personal problems. But the rectangle? It seems you are always the last to know. And the squiggle? Why do you embarrass your friends?

These ideas are not new. Shape and character have long gone together. There was Johann Kaspar Lavater who presided over the craze of head-reading. And there was his close friend, the artist Henry Fuseli. In one of his aphorisms, he pronounced: "The forms of virtue are erect, the forms of pleasure undulate. Minerva's drapery descends in long uninterrupted lines; a thousand amorous curves embrace the limbs of Flora."

Fuseli's equations are primarily tips for the artist. Upright, that's the way to convey virtue. No doubt they could be adapted into a personality test. (Undulations? You are the amorous type.) But Fuseli's priorities were creative. He wanted to embody feelings.

His painting called Silence seems to have been made according to a shape-character programme. Its shape is so explicit. This image is occupied by a single, strong, simple form. A sitting cross-legged figure is bent right over itself. It is composed into a self-enclosed shape. As far as a human body can be, it's rolled up into a ball.

The form could hardly be clearer. But what it means or expresses, is not so clear. Silence? Take away its title, and you could find many alternatives. Or try to complete the phrase: "The forms of .... are enclosed." There's no obvious single answer.

Perhaps the link between shapes and meanings isn't so sure. This image can be a test case. It presents a very definite form, in a very pure state. It's powerful, all right, but with little to focus its power.

Where are we? Nowhere. There's darkness, and within it just enough light and cast shadows to indicate floor and wall, some kind of cavern or niche, in which the figure squats. Around it there's a void of non-specific gloom. The scene might be set, not in some real if vague location, but in a metaphysical space.

And who is this presence? A kind of nobody. There is no story or myth suggested, to give us emotional context. The figure is probably male, but not certainly. Its hands could be female. Its garment is ambivalent. Its cascade of hair is too. Its age is indeterminate. Its glowing monochrome hints at a ghost as much as a body. It might be sage or sibyl, spirit or symbol.

Its most extreme feature is its head. It's bent over, level with the shoulders, and is almost identical to the shoulders, three blobs in a row. Its long hair looks like a third limb hanging down between the arms. No facial expression, then: the head hides within the body. This being has sunk into itself.

Sunk is right. The pose and the shape might have a sense of strain, of imposition, as if the figure had been forced or forced itself into this ball. It might have looked agonised or imprisoned within its containing form: hunched shoulders, clamped arms, as in William Blake's versions of this pose. But the figure in Silence has no rigidity and no resistance. It relaxes into its closure. And if you look at it, blurred or from a distance, you can see it that it's like a closed hand (thumb on the left): not a tight fist, a softly closed hand.

But expressing, meaning what? It's a deep state, no doubt, because the form involves the figure so fully. And obviously it's not a state of elation or extraversion: this is a turned in and drooping form. Yet nor is it a state of real pain, because this figure surrenders into its form.

You could find a range of feelings here. It is melancholic, dejected; it is pensive, meditative; it is withdrawn and secluded there are all these possibilities, related but distinct. On the other hand, you don't find the hard feelings that might go with this form like depression, or repression, or defensive egotism. The figure isn't in that kind of grip.

So Silence speaks in an abstract emotional language. Its feelings go inwards and downwards. Its feelings are soft and not hard. Beyond that, it doesn't say anything specific. It's too basic. It's an archetypal figure, personifying a very fundamental state of the human mind. True, if this figure belongs to one of the shape-personality types, mentioned above, it surely has to be "circle". But you probably wouldn't go to it with your personal problems.

About the artist

Henry Fuseli (1741-1825) was a high-minded artist who seems not to have quite realised or admitted his highly original talent for sensation. He was Swiss-born and he trained as a priest. He moved to London. He looked back to the noble sublimity of Michelangelo and the Greeks. He was deeply inspired by Shakespeare and Milton. He took a pioneering interest in Norse mythology. And he invented a pictorial theatre of sexual bondage, bug-eyed madness, creeping horror, witches, fairies, spooks and grotesquely posing musclemen. His 'The Nightmare', in several versions, is a classic of gothic. It's a world half-comic in its excess, which proved an inspiration both to contemporary cartoonists like James Gillray, and to the superhero comix of the 20th century.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments