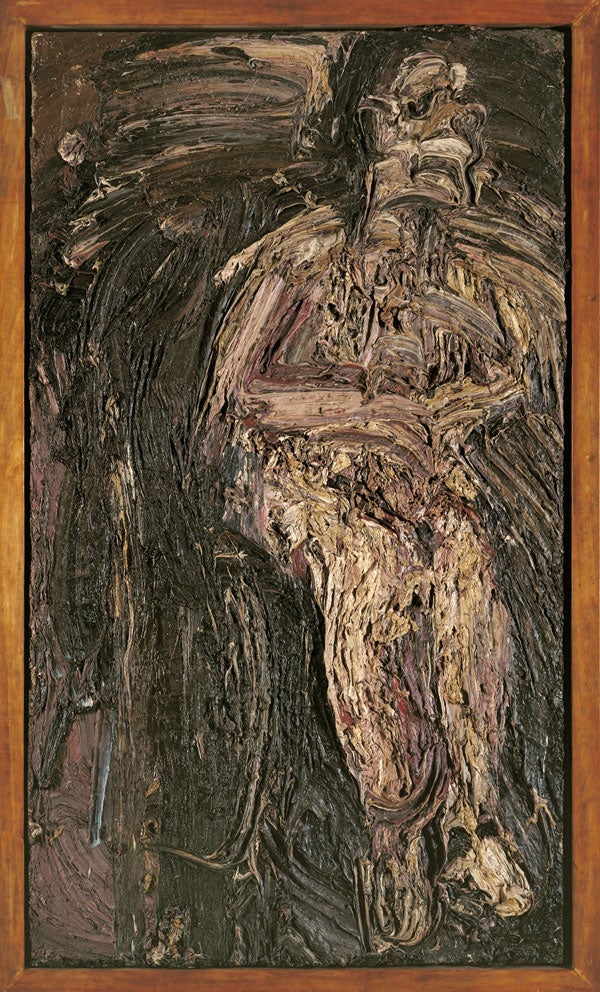

Great Works: Man in a Wheelchair (1961), Leon Kossoff

Tate, London

Paintings can look composed in two quite distinct senses. They may appear to have been built up in parts, with a certain amount of careful pre-planning. Perhaps they began in an entire cycle of working drawings. Renaissance altarpieces often look composed in this way. They have been tailored, organised, to please the patron, to demonstrate the respective size of saints and donors perhaps, so that the donor shall not feel hard done by. If Rubens were the painter, he might well have produced an oil sketch to give some concrete notion of the finished piece to the patron. Then the squabbling could begin.

Paintings may also appear composed if they possess a smooth air of settled serenity. Eighteenth century portraits often have this second quality. There is a smoothness about the surface of the painting, and about the painter's treatment of the sitter. The sitter would have wanted this to be so of course in order to have reflected back at him the fact that she or she was the very embodiment of stability, tranquillity and dignity, the master – or the mistress – of all that he or she surveyed, quite as far as the ancestral acres extended. Perhaps even a little farther. This is how things were meant to be in this settled world, we feel as we stare, cap in hand, into a face by a painter such as George Romney. And that is exactly what the sitter would have wanted us to feel.

This portrait of a man in a wheelchair by Leon Kossoff, painted in 1961 when Kossoff was in his middle thirties, does not look composed in either of these senses. It looks as if it has arrived in this world after an almighty shriek of pain, fully formed. This is why it alarms us, even today, when we stand and stare at its huge, looming, molten presence in Tate Britain. It is much taller than life-size and, frankly, it looks not so much like a painting as a weary, blasted battle ground that has been fought over again and again until some kind of exhausted victory has been achieved by one side or the other. But what exactly has Kossoff has been fighting against in the extraordinary portrait of this anonymous man? He has been triumphantly fighting back against his own settled belief in his own profound inadequacies as a painter.

Kossoff makes his paintings and his drawings in a very particular way. Now in his eighties, he draws, every day, in order to prove to himself, over and over again, that he can draw. He has been a regular visitor to the National Gallery since the age of 14, and there he draws the old masters, often as fast as possible, endeavouring to catch life – the life particular to any painting and any particular time of day – on the wing. Every time he looks, he sees a slightly different painting. An arm is articulated in a slightly different way or a cloud has a very particular impact upon a running figure. This is something that he had that he had not spotted on the three-hundred- and-nineteen times he had looked at that Titian before. These drawings often look like speedy notations. They are. They are not in any meaningful way movements towards a painting. He does not make preparatory drawings from which a painting will be composed. He draws every day in order to practise making discoveries.

With his paintings it is quite different. He works from models, but again it can be a frenzied process. He builds up layers of paint and then he scrapes those layers off again. The next day, he stands in front of that same sitter, and then he does the same. He scrapes that layer off too. There is a terrible violence – the violence that comes of dissatisfaction with one's inadequate efforts – about this seemingly endless process. But, no, it is not in fact endless. Eventually, the painting does click shut like a box. Something has been done right. Needless to say, the studio is an appalling mess of paint-streaked walls and floors. How could it be otherwise?

But what kind of brute is this man? That's how we think of him, as a brute of a man. He exists beyond the social niceties. He is man in extremis. So much raw, naked exposure of the essence of the idea of man-in-wheelchair. The head, the face, look horribly stretched, wrenched about. The paint is thickly gathered and bunched in pushed, driven heaps – thick, clotted mustards, mudded yellows, creams, mauve, edging towards the colour of dried blood. The man himself appears to be jammed, violently parked, unceremoniously, off-centre, against the right-hand side of the canvas. We know so little of him, so little real detail of his human presence. And yet, simultaneously, we know everything, more than we could ever wish or need to know and it horrifies us and disgusts us because he has been dumped here, the helpless portrait painter's victim, rendered in the pitiless, pared-back style of all the horrors of the 20th century, before us, and then squeezed to such an extent – like an old grey rag – that this is as much as is left of him, and, thank God, it is more than enough. Why would we want more than this wrenched, rubberised mask of a face with its blethers of streaked, clotted white? Yes, this really is more than enough.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Leon Kossoff was born in Islington, north London, in 1926. He paints structures and people, family and friends and buildings that are usually well known to him – a railway siding, street life, markets. His style could be called existentialist – his portraits are often extremely dramatic visions of man alone in the world, nursing his isolation, thickly textured to draw attention to the facture of the painting.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks