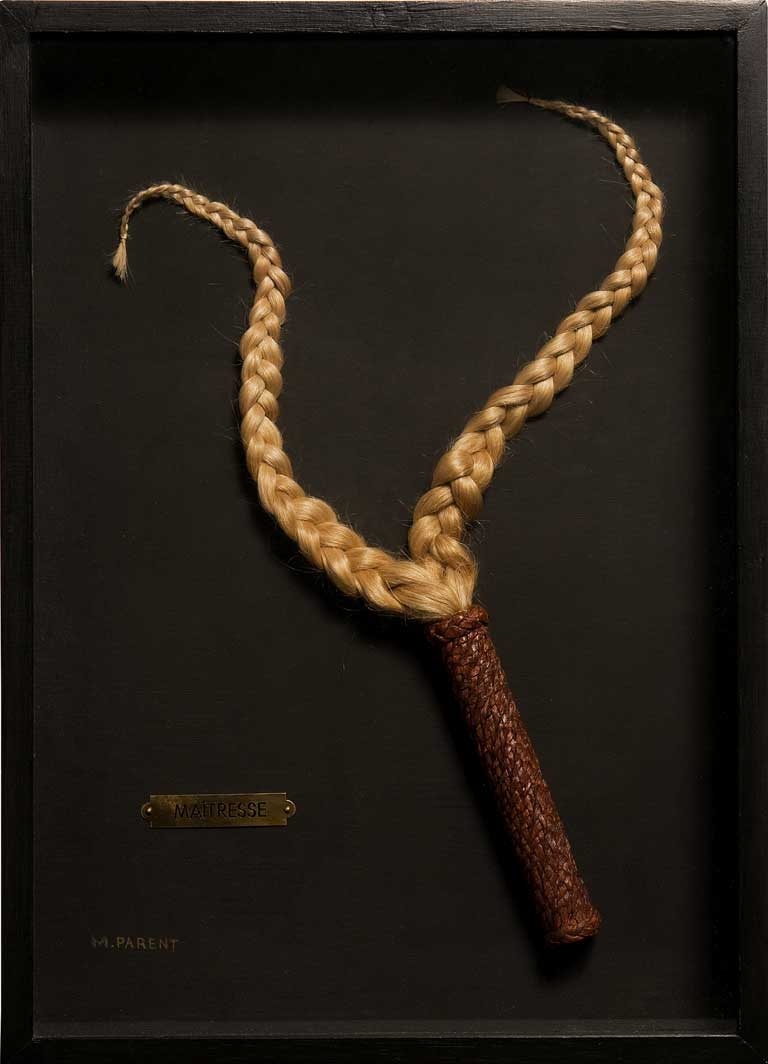

Great Works: Maîtresse, 1996, by Mimi Parent

Collection Mony Vibescu

Here is art as weaponry, wielded by the female of the tribe. Or perhaps weaponry as art. Were this a painting of what it depicts, it would be much less delightful, and its message much less forceful and thought-provoking. The work itself seems to sit inside a dark and shallow box, which frames it and tames it somewhat.

No, it is surely more than that. This frame is more than a mere technical device. It is working for its money. It is part of the presence and the meaning of this piece – rather in the way that Joseph Cornell's boxes – large, small, shallow, deep – contribute to the meaning of whatever it is that they happen to contain. Here, the object feels trapped inside that box. Or does it? Not quite true, we feel, on further rumination. The box is as much a part of the work as that which it contains.

The threatened containment by the box may be encouraging an element of fightback. Perhaps this is the maître trying to bring the unruly maîtresse to heel. That is surely the import of the title. The maîtresse is already to heel, of course, in a sense, because the word maîtresse is a mere three-letter extension of the word that has helped to bring it into being. The maîtresse has already been subjugated by the maître that forms part of her name. And that is the point of all this, and of many other works by female Surrealists (and there were many of those), that she cannot and will not accept such subjugation. After all, barring a single letter, she would be esse – the hissy latin verb "to be" – were she left to her own devices.

Is this maîtresse a kept woman? Is this a kept whip? Once again, the answer must surely be yes and no. There is delicious equivocation here. The whip is both a symbol of the maîtresse, her visual embodiment – how she walks and how she swings her hair and her hips perhaps (there is a lot of alluring female posturing in this whip, for all its potential to lash) – and it is also everything that she is reduced to in her fury of subjugation. She is nothing but this urge to take vengeance And, thirdly, it is the weapon that she is capable of wielding. She is also a de Sade(sse) then.

The whip itself is both a simplified representation of the female body in motion in space – see how, rather delightfully causally, it seems to lean back into the wind as it walks – and nothing but a whip, formed from the braids of the artist's own blonde hair (which may comprehend head and hair), with that columnar torso providing us with a visual sketch of all the rest. (There is an interesting biographical detail to be inserted here: this artwork was created, these braids sheared off in preparation, because the artist discovered that her partner had been cheating on her). The whip feels both light, loose and sexually teasing, and savage in intent. These braids are also reminiscent of a stag's antlers, poised to strike. They are touching, too. The whip feels terribly vulnerable, even child-like. Braids more usually define childhood. They also gave Rapunzel, once let down, her freedom. It is perhaps the child in the woman lashing back who has been wronged then.

The work is simple enough to be the work of a child. Its simplicity almost makes us laugh, though it is laughter of a rather uneasy kind. A whip in a box is also an impotent thing, it has to be said, more an after-thought of vengeance.

About the artist: Mimi Parent (1924-2005)

Mimi Parent was born in Montreal, and spent much of her adult life in Paris, where she officially joined the Surrealist group in 1959, and was very active in it as exhibition organiser and exhibitor thereafter. Many of her works consists of hauntingly bizarre scenes staged inside boxes, reminiscent of fairy tale or folklore.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks