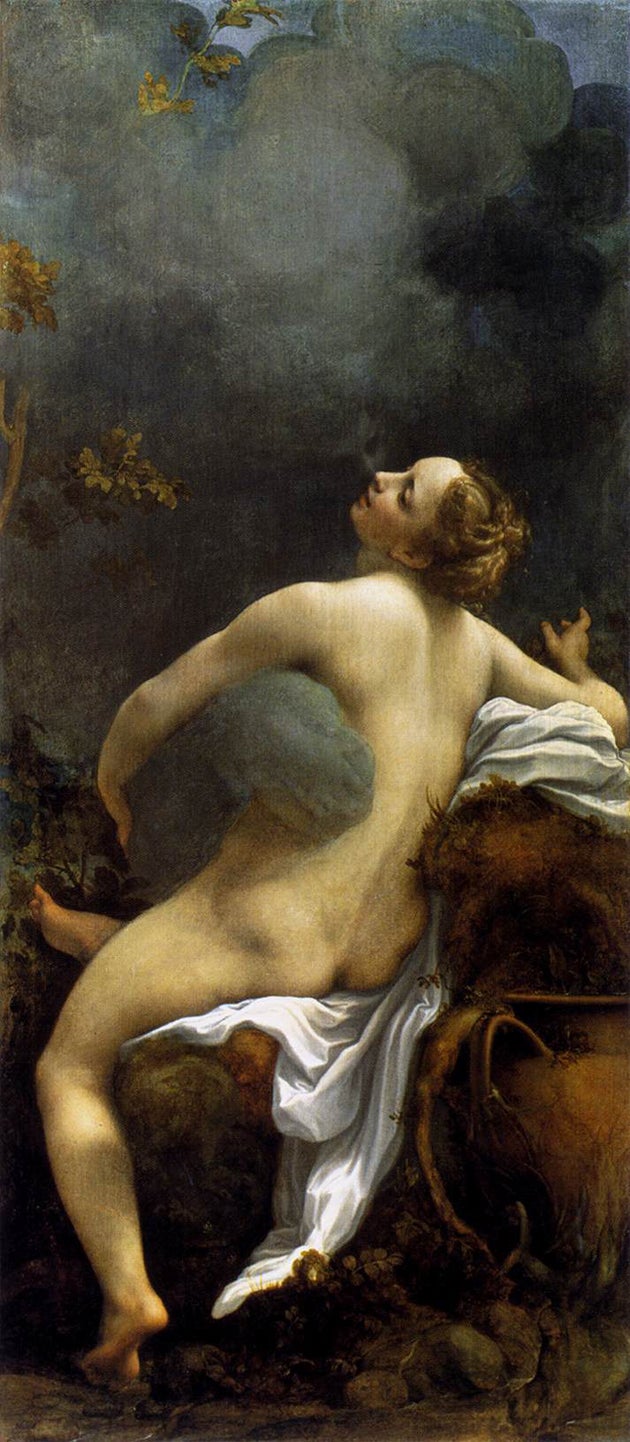

Great Works: Io (or Jupiter and Io) (1530), Correggio

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Some Japanese exotic erotic prints are beyond belief. There is a scene by Hokusai, for example, involving a naked girl and two octopuses. Her eyes are closed, and the girl seems lost in total ecstasy or even in deep sleep. The little creature has its kiss fastened passionately onto hers, and with a tentacle spiralled around one of her nipples. The big creature has its vast mouth entering her vagina, and its tentacles are spreading all over her body. And when you notice her hands, gripping her larger sea-lover, she appears to be rather more conscious. This is a direct act of sex.

The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife comes from around 1820. This is not the kind of imagery that we expect to meet in Western art at any time. Of course, there is plenty of pornography in our lives. European bodies can be found using another in any combination of orifices. But in this Japanese print there's a level of invention, delicacy, complexity, comedy that is quite a different thing. It creates strong aesthetic pleasures. It is both extremely frank and richly imaginative. It is, by any other name, an art.

And how can Western high art illustrate sex in a way that shows bodies with direct contact? It can be done, but only with the most careful treatment. Obscenity is clearly excluded. It needs a blend of insinuation and discretion. Indeed, it may involve a very peculiar performance. Look at this love scene. Correggio's Io is celebrated as one of the masterpieces of European erotica, but it shows no explicit private parts. Frontal nudity often appears in many paintings; not here. What we see is a story.

The nymph Io is pursued by the god Jupiter. It's a transformation scene. We see him having sex, with a mortal woman, via a disguise. And sometimes he's a swan, or a bull, or a shower of gold. But in this case he manifests himself in a more extreme form. He does not become any kind of solid. Jupiter changes into a cloud.

And immediately the question of sexual intercourse is a more doubtful issue. For can a body and a gas make love? Is this god really in contact? Or again, take the other side of this relationship. How can the woman make her response? Io is more or less directly facing her lover, but she seems to be lost in her own private dreams of pleasure.

The nymph lacks full reciprocal consciousness. True, you can't say that she is actually asleep, anymore than the Fisherman's Wife is asleep. Her right hand is posed. Her left foot is propped onto the ground. Her limbs are arched and her contours have vivid serpentine curves. She is full of sensation.

But her body is flopped over this pile of earth and sheet, and her left arm is merely supported on this pillow of cloud. Her eyes are half closed. Her mouth is half opened. Her head is falling back. Her face suggests an ambiguous state. And how far it goes is hard to say. Passive, submissive, languid, sedated? There is no pressing or active desire. She makes herself – at most – available.

And then there is the god. He is unable to make physical contact. You might suspect this man to be taking a hard advantage of this soft half-hypnotic condition. On the contrary, he is himself softened. His body is surrounded with mist or steam or ghost. Whatever his solid skin might be, it cannot caress hers.

The veiling grey cloud holds his right hand within it, and doesn't make any impression on, any grasp on, the woman's waist. Likewise, Jupiter's head seems to be hovering deep in its cloud, looming from the air, without any meeting of mouth and face. This ghost is an outer spirit. The inner man doesn't emerge into touch. It is a strange materialisation.

So this is a non-act of sex. It is a paradoxical situation. This man and this woman, both naked, could hardly be more close. And on the other hand, they are utterly separate. Their positions imply a total intimacy. Their actions are helpless, empty. Their kiss, their embrace, their possible penetration are nowhere. They lie in dreams of impossibility.

Or perhaps in the painting there is one strange moment of obscenity. The nymph's flesh reveals it. It becomes a point of hard touch. Look at her right foot, and how it pokes out from behind her left thigh. It is puzzling to say where it comes from, or whether it is connected to the rest of her body at all. It just emerges there. It sticks up in isolation. And it has a place and a shape and an angle that suggest something clearly phallic.

The male body could obviously never show it, but a substitute can do this job well, and with a shock, a subtlety, that even Hokusai can't equal. It feels very rude.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Correggio (c 1489-1534), aka Antonio Allegri, is now a slightly absurd Italian painter, but in his time his art was both spectacular and brilliantly expert. He developed grand domed ceilings, with illusionary heavens, with clouds and saints in rings within rings, hovering above the viewers – for example, the 'Assumption of the Virgin' in Parma Cathedral. His images of the lovers of Jupiter – including Io, Ganymede, Leda, Danae – are daring in their sensuousness. His painting became famous for its extreme softness, its "morbidezza", meaning that the edges are fused and the tones are blurred. There was a joke term coined at the expense of art connoisseurs. It was called the very "Correggiosity of Correggio."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments