"War is inside all of us": as VE day nears, artists from Maggi Hambling to Jeremy Deller discuss commemorating conflict

As the popularity of the Tower of London poppies showed, we need a reflective take on war’s unexplainable horrors more than ever

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was last year’s biggest art story: before the installation Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red opened at the Tower of London in August last year to commemorate the centenary of the First World War, it was expected to provide a spectacle, but no one predicted its impact. Come its closure on 12 November, the sea of ceramic poppies had attracted more than four million visitors and captured the national imagination. “It was rather a marvellous thing as it made it possible for a lot of people to remember in a very universal way,” says fellow artist Maggi Hambling of the work by Paul Cummins and Tom Piper.

What its popularity made clear was just how much we need a reflective take on war’s unexplainable horrors, in an age of rolling news bombarding us with images of conflict. And with another round of commemoration this week – for the 70th anniversary of the end of the Second World War – visual artists are arguably the people best able to offer that.

Hambling is one such war artist: the 69-year-old has long grappled with conflict and death in her work, despite having stayed away from front lines: she was invited to go the Falklands as the official war artist in the 1980s, but didn’t take up the offer because she did not “think a shot would be fired”.

Her new exhibition, War Requiem and Aftermath, at Somerset House in central London, is a summation of her work on the subject, from painting to sculpture and installation. What has drawn her so often to war I wonder? That’s looking at it wrong way round, she says. “One of the most important things an art teacher told me was that an artist doesn’t choose the subject, the subject chooses the artist.”

That sense of compulsion is clear from the works’ fierce power, among them a series of gnarled sculptures in painted bronze that are “very much inspired by gargoyles on churches”. But the exhibition’s centrepiece, an installation called War Requiem 2, counterpoints the ugliness of conflict with the beauty of another of Hambling’s great interests, Benjamin Britten: a room filled with swirling, abstract portraits of anonymous war victims and ravaged battlefields, soundtracked by Britten’s War Requiem and entered one by one. “I will never forget hearing that piece for the first time, the grandeur of it, the chilling nature of it and the repetition of the church bells and the tenderness and the strangeness … [it] sounded like a voice from another place,”she says.

Another major artist compelled to reflect on war in recent years is Turner prize winner Jeremy Deller: he made waves in 2009 with It is What it Is, the shell of a car destroyed in a 2007 truck-bomb attack that killed 38 in Baghdad, which toured America before being installed at the Imperial War Museum. He originally bid to have it placed on Trafalgar Square’s fourth plinth; like the poppies, though a whole lot more brutal, its power lay in its sheer spectacle.

“The public can complete art and make it whole, make it living [even if it is] about death,” he says. Even within the confines of a museum, it proved a national talking point, and while it has been read by some as an anti-war statement, Deller has refused to ascribe it a political position, leaving that open to its audience. “[The war] was something I was bothered about as we all were,” is what he says simply. “I felt I wanted to do something about it or with it.”

Set against such “long distance” war artists are those who depict it from experience; the value of their work is in the detail as much as the drama. Take Arabella Dorman, who has been both an official and unofficial war artist in Iraq and Afghanistan, and whose exhibition Before the Dawn – An Artist’s Journey through Afghanistan, overlapped in London with the poppies display. In contrast to Hambling, her style is representative; her Afghan paintings include battlefield scenes along with portraits of British soldiers killed on the field and paintings of Afghan people trying to get on with their lives.

Are there compromises an artist must make when working in an official capacity? Dorman says she was “given no remit by the Ministry of Defence. There is an implicit trust there. As a painter I was given a longer rein [than a journalist] as I wasn’t going to reveal very much in my work [about military tactics]. I don’t really see my paintings as representing war so much as representing the human face of conflict.”

She is drawn to paint war because: “Life on the front line is condensed and cut down to its essentials; there are few places more compelling than the theatre of war … to see that level of trauma and suffering up close and to see alongside it the incredible self-command and control the commanding officer had over his men, was very humbling and moving.” But as she spent more time with the Afghan people, Dorman’s work took on different emphases: rather than focusing only on the horror of war, she was drawn to break down “the dominant narrative about Afghanistan [by] portraying the people in a broader context”, rather than as “victim” or “enemy”.

“There is so much more that emerges and so much more beauty that can be found in conflict, hidden moments that reveal the strength of the human spirit that can emerge out of adversity,” she says. This can be seen in works like Walking to School which shows two girls in headscarves making that daily journey, an act of defiance in a country where girls’ education is often violently disputed.

Another artist aiming to redress the simplistic media narrative is John Keane. Official war artist during the first Gulf War in 1991, he has two exhibitions opening this month at London’s Flower Galleries, both on the themes of power and conflict.

When Keane first went to the Gulf, he says he tried not to set out with preconeptions. “My aim was just to be a sponge – absorb and record as much as possible,” he says. “I didn’t know how I might react. The whole experience was very alien and disturbing. Like a dream that I awoke from on my return.”

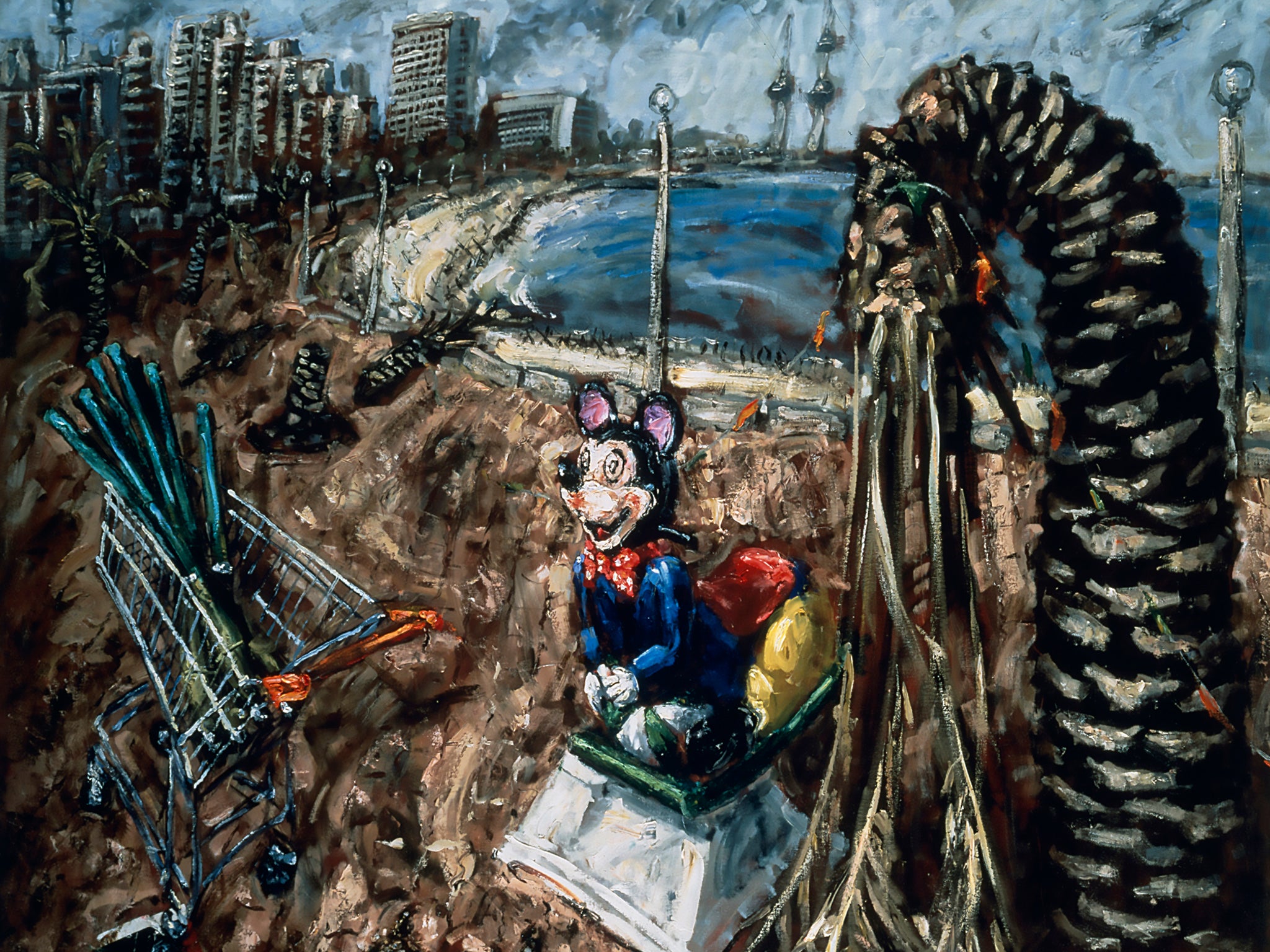

But what he quickly realised was that “it was important that my work should address not only the conflict, but the media coverage of the conflict as well”. That resulted in paintings that provided a subversive perspective on the “us vs them” narrative, the most famous being Mickey Mouse at the Front, referencing America’s influence on Iraq, which he painted after a seeing a broken Mickey Mouse amusement machine in a room used by Iraqi soldiers as a toilet. “This kitsch, grinning cartoon character presiding over a room full of excrement demanded my attention. Of course I never could have predicted an image like that, so symbolically loaded.”

Such work has not dated of course. “Gulf One was not an isolated historical event, but perhaps the opening salvo on a war that is still going on, being waged with greater ferocity than we could ever have imagined,” says Keane. “9/11, the ‘War on Terror’, Islamic State are all events in the same continuum, and I’m still addressing these in my current work.”

Though the most powerful war art transcends even historical details: as Hambling says, to address war is to address the essence of being human.

“War seems to be inevitable. The moment one war seems to be over several more have started; it seems to be a human condition…. War is inside all of us. We can all get angry. But I think an artist of any kind is very lucky as instead of murdering somebody they can write an opera.”

‘War, Requiem and Aftermath’ runs until 31 May at Somerset House, London. ‘John Keane, the Wisdom of Hindsight’ is at the Flowers Gallery, London E2 from 21 May to 20 June.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments