Donald Trump and the power and origin of the naked protest

When 100 semi-naked protesters marched on Trump Tower last month, some had decorated their bodies with fake wounds and scars representing the damage his administration might cause - joining a long history of naked demonstration

Donald Trump’s road to the White House has been punctuated by as series of naked protests, ranging from topless women at Trump’s polling station to Spencer Tunick’s nude installation of 130 naked protesters outside the Republican National Convention in Cleveland. These protesters continue a long history of naked demonstration – and nakedness has long been employed as a gesture of defiance, highlighting the plight of the oppressed.

In a time when media is saturated with nudity, the naked body might seem to have lost its power. But amid fears that Trump’s administration will set back women’s rights by decades, naked protest may have regained relevance.

When 100 semi-naked protesters marched to Trump Tower on 19 November, some presented their bodies as metaphors for the human planet, sensitive to climate change. Others used their bodies to express a fear that women, under Trump, would become a marginalised group. These protesters’ nudity is a defiant response to revelations during Trump’s campaign about his attitudes towards imperfect bodies, confronting Trump’s “man of the people” act by showing him what real America looks like. If Trump is to represent “ordinary Americans”, he must learn to accept them in all shapes and sizes.

But these were more than just naked bodies. Protesters had decorated their bodies with fake wounds and scars, representing the damage that Trump’s administration may cause. This is a warning that if the administration wields too much power, the powerless will suffer.

Trump’s election has left many Americans feeling overwhelmingly powerless. It would make sense, then, for them to resort to a method of protest that has long been associated with oppressed and minority groups. Undressing is a tool that is at almost any protester’s disposal: a last line of defence that is almost universally accessible. It is an act of defiance that is still available even to those who are disempowered by low status, by lack of funds, or simply by ordinariness. So Mexican farmers protesting government appropriation of their land in 1992 turned to naked protest as a last resort, explaining their action by saying “we are stripping because … we don’t have money to buy an ad in the news … we have no other arms, all we have are our bodies”. This movement, which became known as the 400 Pueblos, continues sporadically to this day.

Human conflict is predicated upon the relational power of opposing parties. Power often stems from control of tangible resources, but is also exercised symbolically, through bodily gestures. Foucault’s writing on subjugation equates power to control of the body. In times of conflict, dominance is asserted through actions that demonstrate control over the “docile” bodies of others. Conversely, to evidence control over one’s own body in the face of an enemy is to maintain control over one’s dignity and identity.

Perhaps the most recognisable example of protest undressing is captured in Ladislav Bielik’s photograph of a man peacefully protesting the Soviet occupation on Czechoslovakian streets in 1968. The image shows him ripping open his shirt to reveal his bare chest, presenting it defiantly to an oncoming tank. His shirt rending is equivalent to the gesture of a raised fist, expressing a pent-up anger so overwhelming that it can no longer be contained internally, and is forced out of the body in the form of a visible gesture. When a bare chest is pressed against a canon, as in Bielik’s photograph, the stark inequality seems unfair. The conflict is revealed as unjust, with the opponents clearly presented as victim and oppressor.

Such gestures appear to transform the sight of a fragile, exposed body into a show of raw force, with the power to overcome the might of opposing forces.

By undressing in public, protesters assert what little power they still have. Undressing is not just a means of removing clothes, but a meaningful gesture that expresses a shift in attitude from compliance to defiance. At the same time, it is a direct challenge to those, like Trump, who are prone to objectifying the female body.

Nakedness has been employed for similar purposes by Femen, in protests against objectification, specifically the feeling that women have been “stripped of ownership” of their own bodies. Femen exploit the power of nudity to counteract “ornamental meanings of female nakedness”, though not because they feel that nudity has innate power; they achieve power via, not through, naked flesh. These protesters present the body not as a passive, erotic object, but as an unpredictable, intimidating Other.

The otherness of the female form is dependent on its unfamiliarity. Historically, the female body has been strange and mysterious, and as a result have been the subject of numerous myths and misconceptions, some of which persist in the US today.

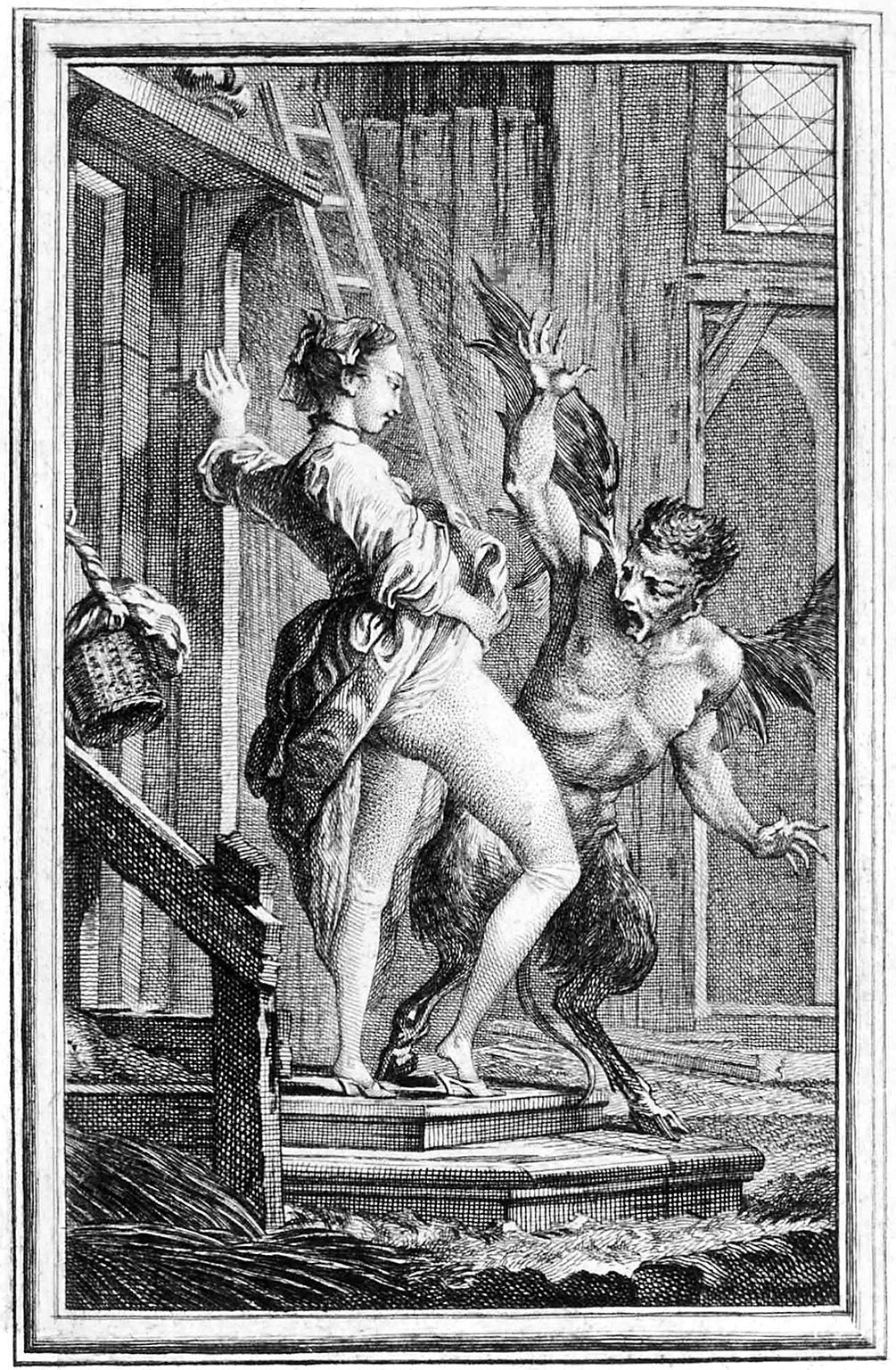

Women of past centuries have been able to exploit the perception of their bodies as peculiar or even monstrous. The Irish legend of Cú Chulainn, for example, describes how, when he turns against his uncle King Conchobor during a bout of youthful revolt, the king sends out a company of women to “expose … their boldness to him”. The young warrior is so intimidated by what he sees that he retreats. Similarly, in Jean de La Fontaine’s The Devil of Pope Fig Island (1674), a woman is able to ward of the devil by flashing her “gash”. Believing the woman’s “gash” to be a wound inflicted by terrible violence, the demon imagines that the woman’s husband must be even more monstrous than he, and retreats in fear.

When their male suppressors are ignorant of the female body and what it can do, women like these can exploit rumour and misinformation to de-eroticise their bodies.

That is not to say that a body must be de-eroticised in order to become powerful. Indeed, there is tremendous power in the erotic presentation of the body, as any burlesque performer will attest. The upcoming World Burlesque Games will demonstrate how empowering it can be to invite objectification in the right setting. Audiences and performers of neo-burlesque locate striptease in a post-feminist world, in which bodies of all shapes, sizes and genders deserve to be the subject of an erotic gaze.

Anti-Trump protesters reveal that this post-feminist ideal is still a distant dream for mainstream America. The mere fact that their nudity attracts press attention is evidence that the US still lags behind more liberated parts of the world in their approach to female nakedness. If the Trump administration does set back feminism, as so many fear it will, naked protest will continue to be an appropriate and effective tool for America women over the course of his presidency. So long as the administration objectifies the female body, protesters will be able to use their own bodies to confront the status quo.

Barbara Brownie is senior lecturer in visual communication at the University of Hertfordshire. This article was originally published on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks