The Socialist Network: Art turning left...

From the French Revolution to the present day, left-wing values have long influenced the production and reception of art. A fascinating and far-ranging exhibition at Tate Liverpool explains how

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.If you’re going to hold an exhibition of leftist politics and art, where better than in Liverpool, where the red flags keep flying although getting more pinkish with the years.

It doesn’t make the task of Tate Liverpool in its new show Art Changing Left any the less challenging. Socialism, as communism, has long since dropped out of intellectual favour, for all the disparities of wealth and the sins of banker capitalism which you might have thought would revive them. In art terms they have become associated with the suppression of individual expression in favour of a populist propaganda as empty as it is heroic.

It was the French Revolution which started it all off, which always made an awkward subject in Britain given the Napoleonic wars which followed. Before then popular art, and indeed radical ideas, were expressed through religion. You could argue, indeed, that many of the values that the left took up of equality and communal effort, and indeed the promotion of local craft, found their voice in the church paintings and sculpture of mediaeval times and the printed tracts of the seventeenth century.

But then religion is even less in vogue today than socialism. What the French revolution did on the Continent, and threatened to do here, was a complete overthrow of old hierarchies and traditional ideas. “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,” as the poet Wordsworth declared adding, “But to be young was very heaven.” The sentiment may seem hollow in the light of what was to come after, but at the time, and in every revolutionary movement since, the joy of comradeship and release remain wonderful in their energy and their youth.

The Tate’s show starts off with a panel of declarations from the 1968 Paris riots, when the students of the “École des Beaux Arts” turned their hands to painted slogans and printed posters. “Leur Campagne est Finie. Notre Lutte Continue” as one particularly dramatic bill has it while another has the conjugation: “Je participe/Tu participes/Il Participe/Nous participons/Vous participez/Ils profitent.”

What the French Revolution also brought into play, however, was the concept of the masses. It was all very well for the painter Jacques-Louis David, and his successors in the Mexican and Russian revolutions, to put his art to the service of monumentalising the movers and martyrs of the moment, but the logic of empowering the working classes and peasantry was the suppression of individual expression in favour of making a communal art in the service of progressive ideals.

Interestingly it is this aspect which the Tate has chosen to pursue rather than the more obvious course of displaying revolutionary art in all its propagandist glory (although it has some of this). What interests it is less the passions of the left in art than how, as the show’s subtitle puts it, left “Values Changed Making from 1789-2013”. It makes for a more cerebral show but in some ways a more interesting one.

One way in which socialist ideals of making the common man part of artistic endeavour was William Morris’ efforts to integrate craft and art. By making the worker a party to the process of creation, he argued, he could break down the capitalist division of labour and the hierarchy of fine art. It may have been fearfully idealistic – although his strictures over the alienation of workers from their product are as valid for the call centres of today as the factories of his time – but it did produce fine textiles, furniture and other objects.

So did his successors in the Bauhaus movement in Germany during the interwar years. The “Arbeitsrat für Kunst” (Workers Council for Art) founded by the architect Walter Gropius and a group of arts in 1919 was, in one sense, opposite to William Morris in that it embraced modern means of production. But it had the same ideal of destroying the old divisions between fine and applied arts and embracing all media in a single whole dedicated to producing products for all people.

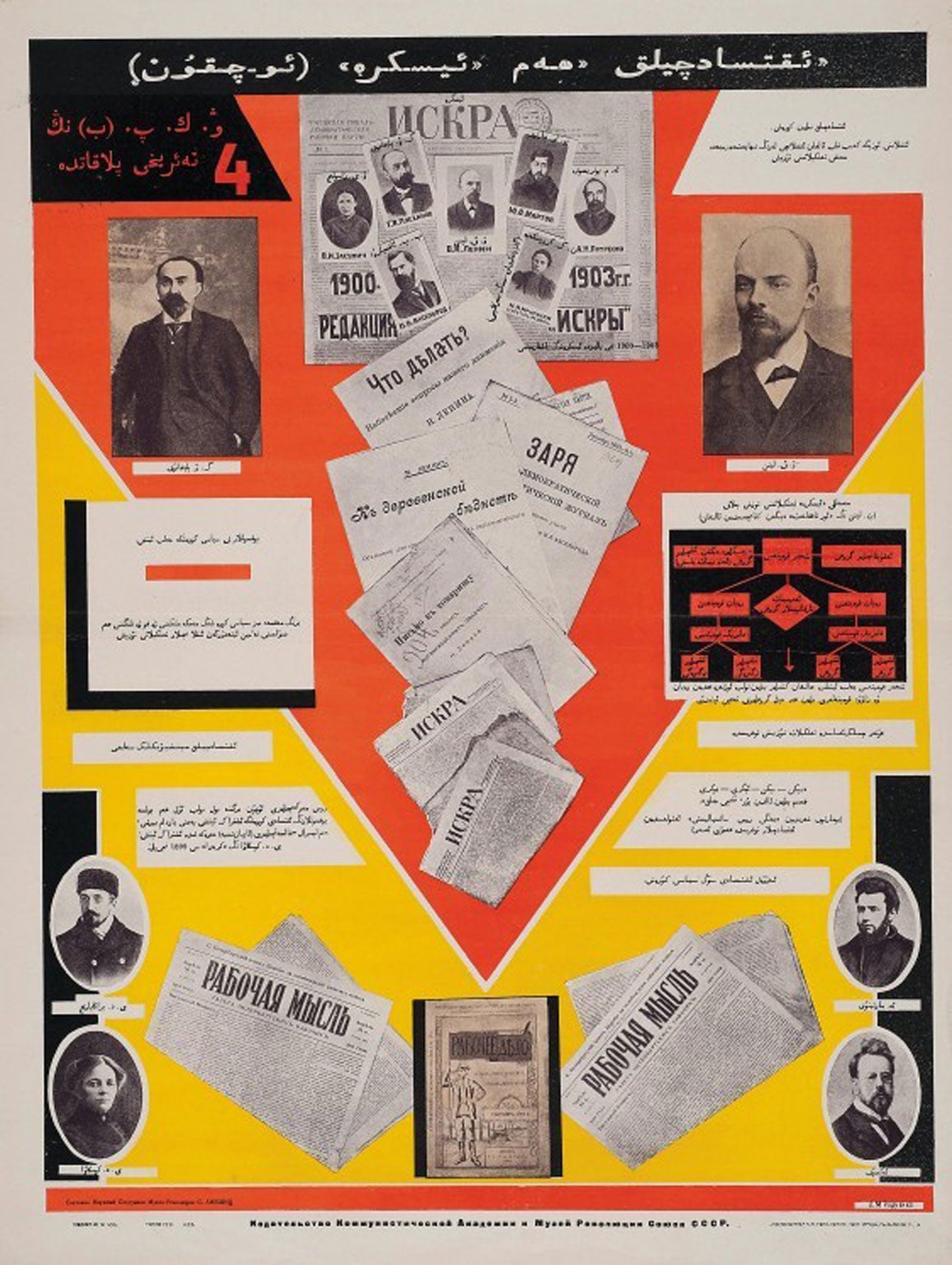

At bottom, however, both the Arts and Crafts movement in Britain and Bauhaus were top-down enterprises, in which the artist gave the lead and attempted to enrol the labourer into their ideals. More revolutionary were the programmes to do away the personal signature in art altogether and produce an art which was completely egalitarian and uniform. Russia provided the most exciting testing ground and the Tate has gathered some particularly optimistic examples of the works produced in the heady days when artists joined the revolution in an eruption of new hope and idealism. Out went the signed work, in came the aesthetic based on firm scientific principles. Adopting the “collectivist” creed of the Communist Party, which saw the individual as only a part of the greater community interest, artists such as Aleksandr Rodchenko and Kazimir Malevich deliberately espoused geometric patterns and organic forms that broke free of individual creativity.

It may sound oppressive – and indeed it soon became so as the bureaucrats determined to root out modernist notions of art and music in favour of popular culture – but Varvara Stepanova’s designs for gymnast uniforms, the photomontages of Gustav Klucis and El Lissitzsky’s “typographic kino-show” remain surprisingly vivacious and forward-looking for all their attempt to create a structured art that did away with the individual voice.

Youth will out and, as the show gathers pace, it becomes something of a roll-call of collectives and groups penning passionate manifestos denouncing all that had gone before and championing an art that was free of elitist concepts of culture and available to the seething masses eager for the clarion call for change. The “Gruppe Progressiver Künstler Köln”, founded in Germany in the 1920s, attempted to develop a visual language that broke the bonds of nationalist linguistics and could reach out to everyone. The British Mass Observation Movement established in 1937 saw in the new mode for social surveys a way of testing what was genuinely popular. The Situationist International was founded to manufacture and distribute works in direct contradiction to the capitalist market in artefacts.

A Stitch in Time by David Medella in 1968 took the form of a bolt of cloth on which the onlooker was invited to stitch their dreams and thought – art made by the onlooker. Goldin and Senneby in the installation Money Will Be Like Dross offered to sell copies of an original alchemy furnace with the proviso that the item would go up in price as each new one was sold, thus reversing the process of the market.

The pomposity of some of the pronouncements may raise a wry smile among the gallery curators and collectors buying the works in the market manner which these groups intended to destroy. They are not easy to display in a gallery setting and the Tate struggles at times to make the works, rather than their captions, tell what they are all about. The nearer you get to the contemporary, the more this kind of art spread into film and performance and away from simple objects. The Tate tries to give some sense of this with a few videos but it’s range is too limited to capture the sense of involvement and passion which modern multimedia happenings and actions on the left take place today, for all that the gallery has introduced an office and education centre, “The Office of Useful Art”, as part of a citywide project to make art part of life rather than solely an object of view.

But then Tate Liverpool is trying to do something different and less obviously pleasing than show the manifestations of the left. Its aim in these thematically organised spaces is to show how the left’s aesthetics, in its rejection of the concepts of fine art and signed works and its embrace of multi-media, modern materials and viewer participation, were part and parcel of modern and post-modernist art. In that Liverpool has refreshingly proved its point.

Art Turning Left: How Values Changed Making 1789-2013, Tate Liverpool (0151 702 7400) to 2 February

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments